In 2001, at the onset of the second intifada, the UJA Federation of NY saw a need to emotionally assist survivors of the terror attacks raging across Israel.

They picked seven Israeli organizations that treat trauma and formed a cooperative network under the Israel Trauma Coalition (ITC) banner.

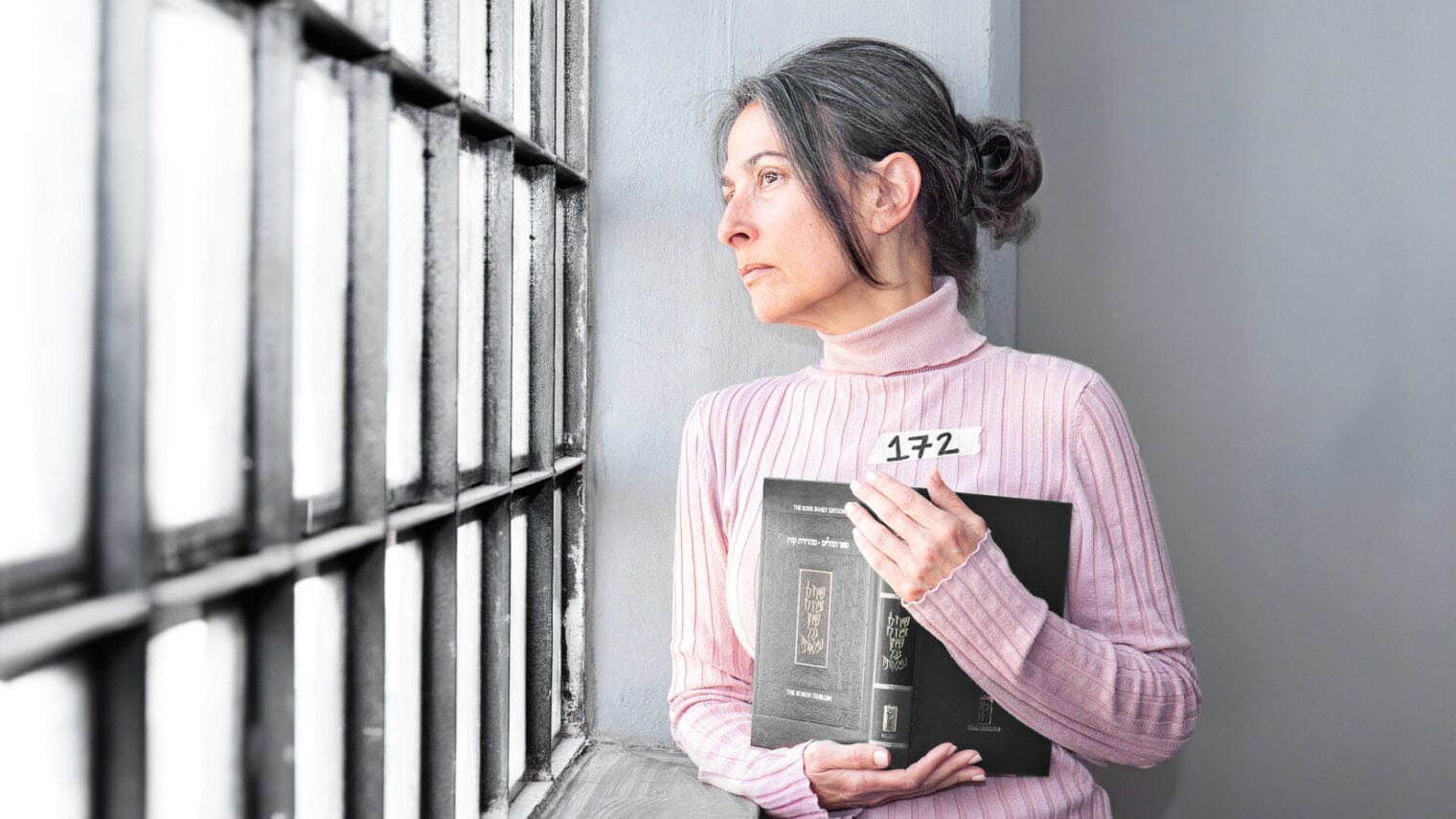

Talia Levanon, a veteran clinical social worker specializing in grief and crisis, was chosen to lead the project and is its current CEO.

“I worked with widows and widowers at the National Insurance Institute (NII), so I got a perspective on what grief is, and later worked with bereaved parents and terminally ill patients,” Levanon tells ISRAEL21c.

Levanon was born in Switzerland and grew up in Nigeria, where her father led projects for Teva Pharmaceutical Industries.

As a teen, Levanon moved to Israel alone and joined the Israel Defense Forces at the start of the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

“I served in an intelligence combat unit and that experience made me a full-fledged Israeli,” she laughs.

As part of her military service, she helped those suffering from post-war trauma, foreshadowing her future life mission.

“In the end, it all comes together,” she says.

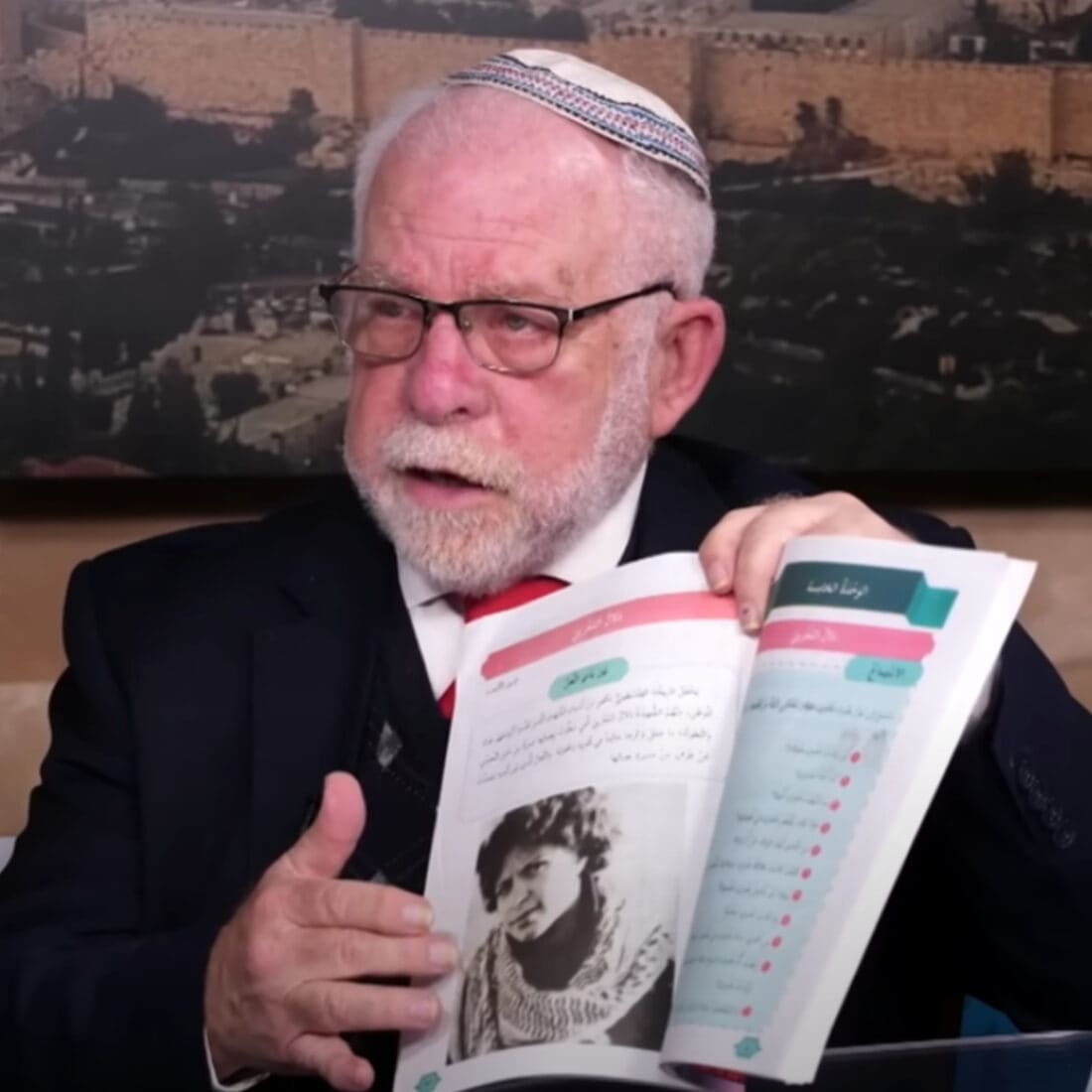

Over the years, Levanon helped transform the ITC from a small project operating with a tiny grant to a respected international organization. It is now an advisory body to the United Nations.

ITC teams have assisted first responders in countless countries during acute crises, such as earthquakes, mass shootings and terror attacks.

Under Levanon’s leadership, the ITC found its unique voice in the world. What separates it from similar organizations is its “Israeli” approach to treating trauma, says Levanon

“We developed unique treatment methods that emphasize strength rather than giving in to being the victim. People who get hurt in security situations always have the strength to overcome it.

“This message is our mission.”

“We, as a nation, won’t go back to what we were on October 6th. But I am optimistic in the sense that resilience means understanding you are vulnerable and learning to deal with it.”

And the mission, says Levanon, is guided by the principles of cooperation, resilience and reinforcement.

“We understood very quickly that those who treat trauma also need to be treated for trauma, whether it’s an ambulance driver or a social worker,” she explains.

Under Levanon’s leadership, the ITC — with the full cooperation of government ministries — also developed the concept of “resilience centers.”

The first branch was established in 2007 in Israeli communities bordering the Gaza Strip, shortly after Hamas took over the Palestinian enclave and rocket fire in the area became a regular occurrence.

“Resilience centers are a unique model. They are established in areas with high exposure to potential security events,” notes Levanon.

Over the years, 12 resilience centers have opened their doors. The centers normally operate during regular work hours, but in emergencies they are open 24/7.

Every center has a team of trauma specialists, such as social workers and psychologists, who offer direct treatment to those seeking help during and after a traumatic event. The centers offer training, helping the staff acquire the skills needed to treat trauma victims.

The centers also work with local authorities to prepare communities for potential emergency situations.

“We started preparing for potential evacuation scenarios [of population centers] following Operation Protective Edge [the 2014 Gaza war], and look what happened on October 7th. Within hours, entire communities were evacuated.”

Local preparedness always has to adjust to the ever-changing reality on the ground. “For example, terrorist infiltrations once wasn’t a thing; now it’s a given,” says Levanon.

“Leading up to October 7th, the therapists and the residents [in the Gaza border region] were all already emotionally drained following years of cross-border fighting,” she says.

The Hamas onslaught caught them off guard.

All the resilience centers located in the areas that came under attack were immediately evacuated, along with all the residents.

“What happened on October 7th shattered our basic assumptions that someone out there, your parents or the army, will always be there to protect you,” she says.

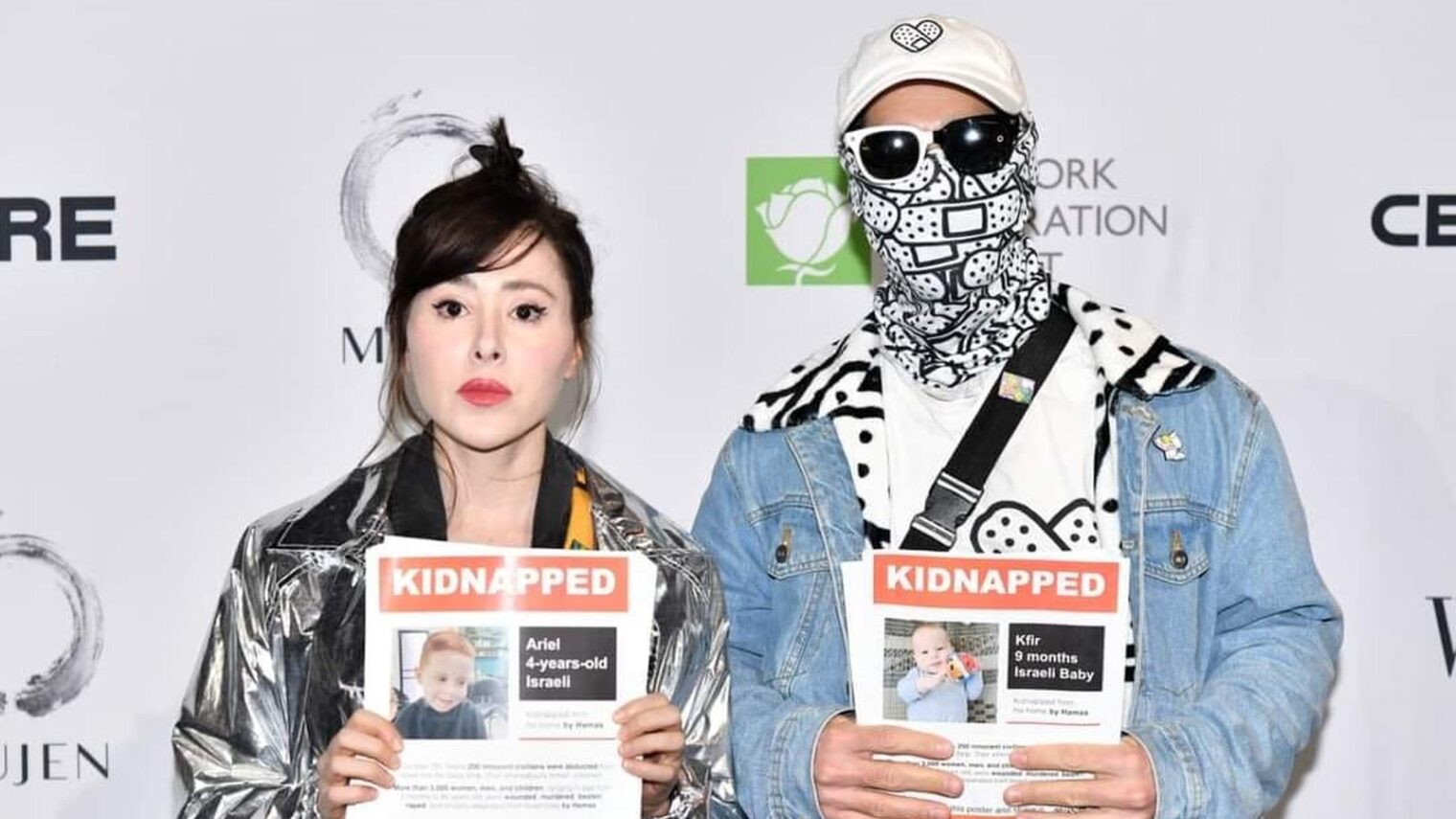

Two of the local resilience centers’ staff members were murdered in the attacks and one was kidnapped. Some staff members, many of whom live locally, lost loved ones. Many more suffered unimaginable trauma of having to escape the Hamas death squads.

Levanon says that one of her close relatives was called up for reserve duty at the start of war, sustained a severe wound following a mortar attack, and returned to the frontlines weeks later.

And yet, the work of the ITC continued, more than ever before.

“In 2022, we treated 6,000 people during the entire year. Since October 7th, we have treated 15,000 people,” says Levanon.

On a personal level, Lebanon has immersed herself in work, and that has helped her keep the anxiety and worry about her relatives, and the country in general, at bay.

As the weeks progressed, the coalition found ways to adapt to the new normal.

In cooperation with the Health Ministry and the NII, the ITC opened a national hotline, *5486.

It is manned by therapists recruited to supplement the 900 already employed by the ITC.

Later, the ITC dispatched teams of therapists to areas where the evacuated communities were temporarily resettled, such as Eilat and the Dead Sea.

As the evacuated residents began to slowly come back to some communities, the resilience centers in the war-hit areas began reopening.

Recently, Teva Pharmaceuticals partnered with the ITC to help recruit and train new therapists as the demand for trauma treatment has grown exponentially.

Levanon adds that neither she, nor most of her ITC colleagues, have had the time to sit down with a mental health professional and talk about their experiences since October 7th.

“We are only now beginning the healing process,” she notes.

“We, as a nation, won’t go back to what we were on October 6. But I am optimistic in the sense that ‘resilience’ means understanding that you are vulnerable and learning to deal with it.”