Sometimes we set off on a meandering path in life and suddenly see a signpost pointing to a perfect place we didn’t know existed.

For London-born Danielle Abraham — a 2008 University of Oxford graduate with a degree in music, who then plunged into a bureaucratic British government job — that signpost was an elderly gent from Israel.

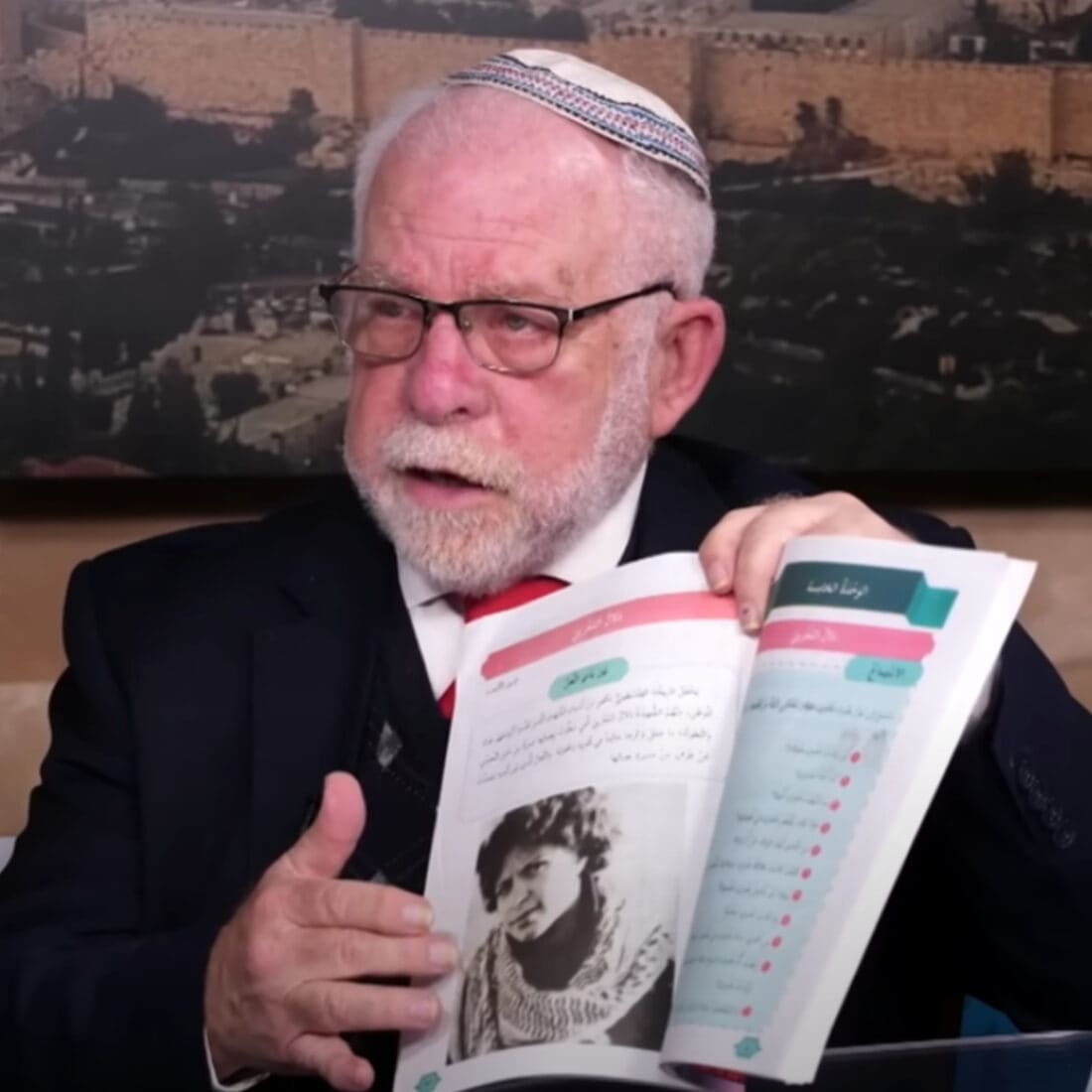

Yitzhak Abt had been responsible for developing agriculture in the Lakhish region of southern Israel and establishing CINADCO, the agricultural aid arm of the Foreign Ministry’s MASHAV agency for international development.

Hearing him speak at a Limmud conference in 2009 inspired Abraham so profoundly that she decided to follow in his footsteps.

“I went home after Limmud and told my family I was going to quit my prestigious job, sell my car, move to Israel and join MASHAV so I could have a career like Yitzhak’s. And they said, ‘You don’t even speak Hebrew!’”

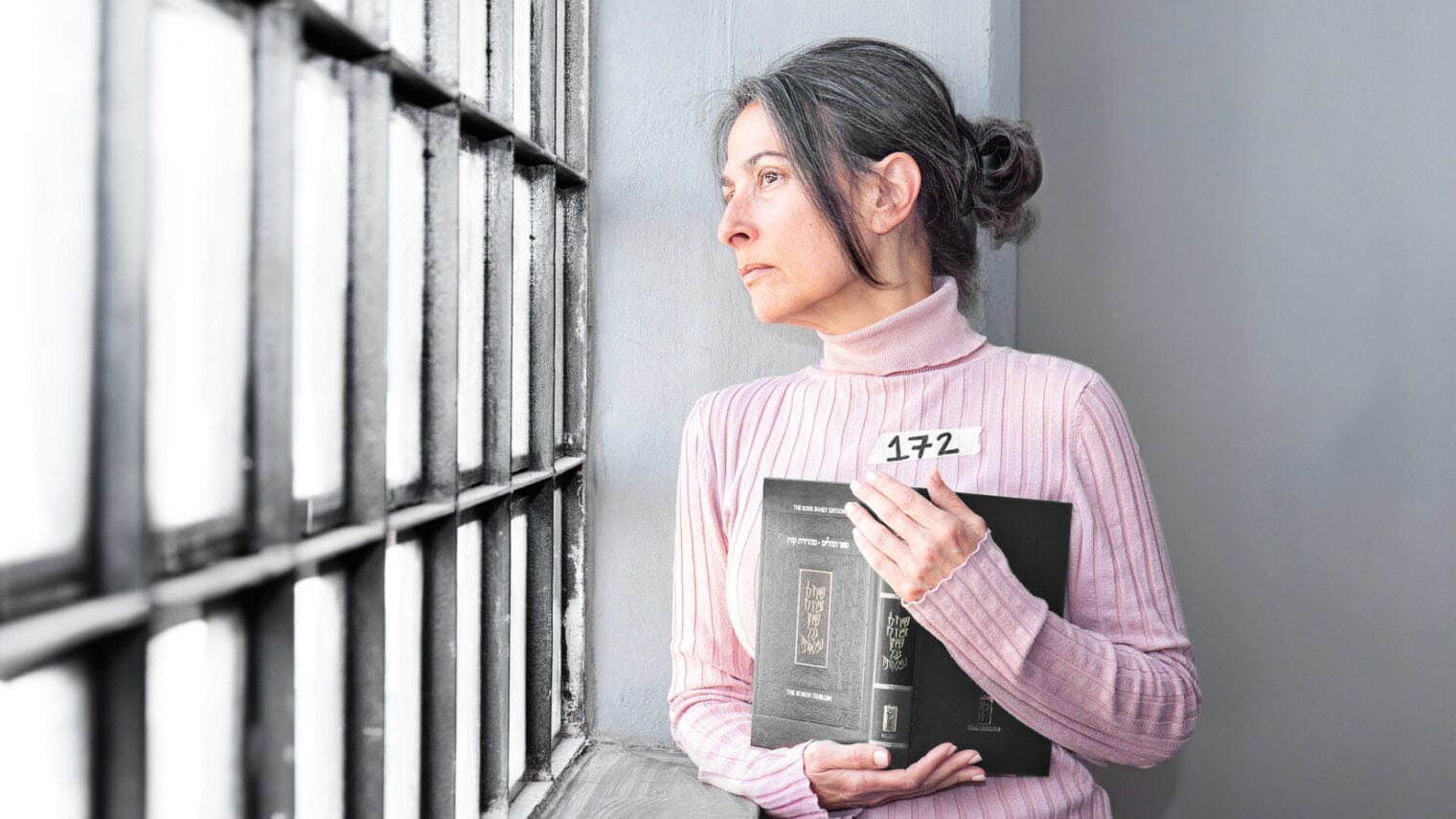

Now 37, Abraham is executive director of Volcani International Partnerships (VIP), a small NGO with a big vision to tackle global hunger using Israeli expertise.

She is also director of VIP’s new ReGrow Israel project, designed to strengthen the future agriculture of the Western Negev following Hamas’ systematic destruction of farms on October 7th.

True to her word, Abraham began working at MASHAV in the fall of 2010 through the 11-month Israel Government Fellowship Program in Jerusalem. The agency sent her to represent Israel at the UN Development Programme for part of that time.

When the fellowship ended, she officially immigrated to Israel and worked for MASHAV in policy planning and external relations for the next three years until leaving to do independent consulting.

Also in 2014, she married an Israeli of Libyan descent whom she’d met in Brazil at Carnivale in 2008. They live in Tel Aviv with their two preschoolers.

In 2016, Abraham met with Prof. Yoram Kapulnik, then director-general of the government’s Volcani Center-Agricultural Research Organization.

Kapulnik told her about an NGO set up in 1983 by pensioners of the Volcani Center and the Ministry of Agriculture. They were mainly focused on giving student scholarships. He felt the organization had potential to be much more under her leadership.

Abraham was intrigued.

“I saw that every time a high-level government or business delegation visited Israel — leaders like Jack Ma from Alibaba — they all stop at Volcani. It’s the beautiful face of Israel, the driving force of agricultural innovation,” she says.

“And they all ask the same three questions: ‘How did you do this in Israel? If you’ve done it, why can’t we? And can you help us?’”

She and Kapulnik established VIP as a vehicle to not only advance Israeli agricultural innovation, but also as the address for these requests, recognizing a huge unrealized opportunity for sharing Israeli expertise.

VIP rests on three pillars: advancing Israeli agricultural innovation; sharing Israeli policy lessons with foreign governments to strengthen food systems; and supporting farmers globally.

While VIP continued the scholarship program and often research at the Volcani Center, the NGO and the research organization are two legally separate organizations.

This autonomy gives VIP a free hand to form partnerships across the world. For example, says Abraham, “We were in the UAE, quietly advising the crown prince before the Abraham Accords. The minister of agriculture in the Bahamas called at the beginning of Covid and asked for our help.”

“We thought it would be a small effort, but it grew bigger because we want to offer strategic solutions effecting meaningful change for the future. The problems are huge, so the solution has to be huge.”

VIP also partnered with AGRA, an alliance for sustainable agriculture in Africa, and The Tony Blair Institute for Global Change writing a case study on Israel’s agricultural transformation, with lessons for developing countries today. Former UK Prime Minister Tony Blair wrote the forward.

The document outlines the “golden triangle” agricultural ecosystem conceived in Israel’s early days. The triangle puts the farmer in the center, surrounded by scientists, agronomists and the private sector to solve every challenge farmers face.

“On the sixth of October, we had big plans to scale our international work. When October 7th happened,” Abraham says, “the VIP board asked what we were doing for the south. I understood quickly that we do have value to add.”

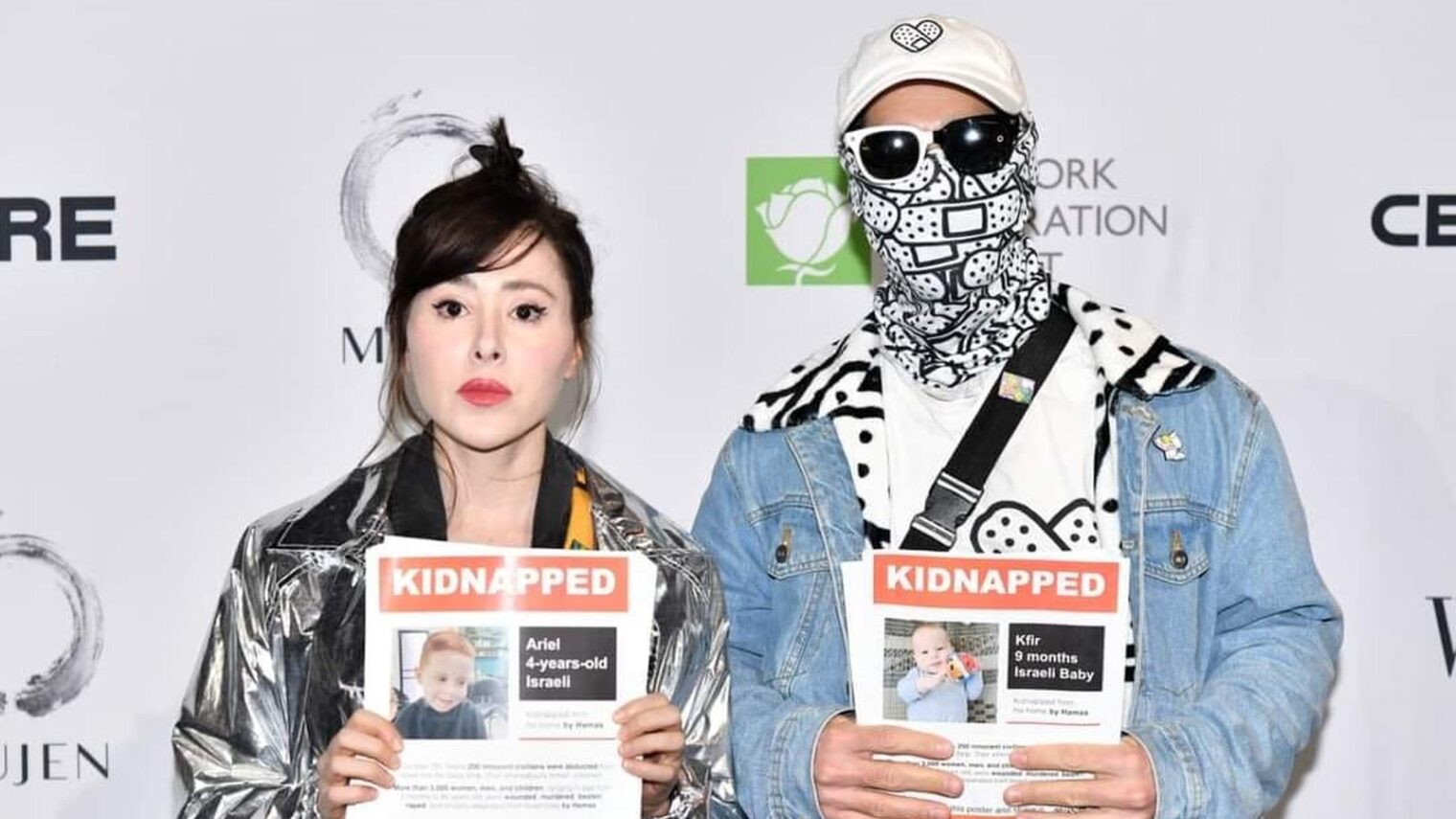

The acts of arson, vandalism and theft employed by Hamas terrorists to destroy farms in the Gaza border area — which supplied 70 percent of Israel’s fresh produce — called for immediate action and long-term planning.

Putting most everything else on hold, Abraham led the establishment of ReGrow Israel as part of VIP, chaired by Kapulnik.

She built partnerships with affected farmers and others and gathered a committee comprising top scientists, agronomists and economists from across Israel, headed by Prof. Itamar Glazer, former director of research at Volcani.

She and her committee met repeatedly with the farmers to assess immediate and longer-term needs.

The initiative started with a $24 million fundraising campaign to replace all damaged or stolen farm equipment.

Then, bringing the golden triangle model back to the farmers in the Western Negev, ReGrow Israel plans to rehabilitate the ruined 40,000 hectares of agricultural land using methods that boost economic resilience and ecological sustainability.

“We thought it would be a small effort, but it grew bigger because we and our partners want to offer strategic solutions effecting meaningful change for the future. The problems are huge, so the solution has to be huge,” says Abraham. “This should be a national mission.”

She points out that the Western Negev is a semiarid environment and sits at the nexus between conflict and climate change, two issues relevant in many countries today.

Therefore, she envisions the Western Negev as a global hub of innovation.

“We have smart, educated, innovative farmers. We have amazing agricultural scientists, agronomists and economists, and a booming agritech sector. We have all the ingredients. We just have to put them together in service of the farmer. If we do, we can come out of this pretty well and share our lessons with the world.”

At first, she was hesitant to “press pause” on VIP’s international progress to address the agricultural crisis at home.

Then she realized that the task is “a great honor” and once again follows in the footsteps of her inspiration, Yitzhak Abt.

“He did the international piece too, but he spent many years developing the region of Lachish. And so much of the knowledge he developed here he then took abroad,” she says.

Abt, now in his 90s, is still her mentor.

“One of the best moments in the past four months was when he called me and said he and his wife saw me interviewed on TV and were very proud.”