The harvest holiday of Shavuot, the Feast of Weeks, commemorates the giving of the Torah at Mount Sinai and “Bikurim” — the first fruits of the grain harvest in the Land of Israel.

In modern times, this ancient festival was given a new lease on life at agricultural settlements celebrating the connection between the Jewish holiday calendar and their products.

The tradition of bringing the first fruits, in reference to the seven species listed in Deuteronomy — wheat, barley, grape, fig, pomegranates, olive (oil), and date (honey) — became a central theme in kibbutz celebrations.

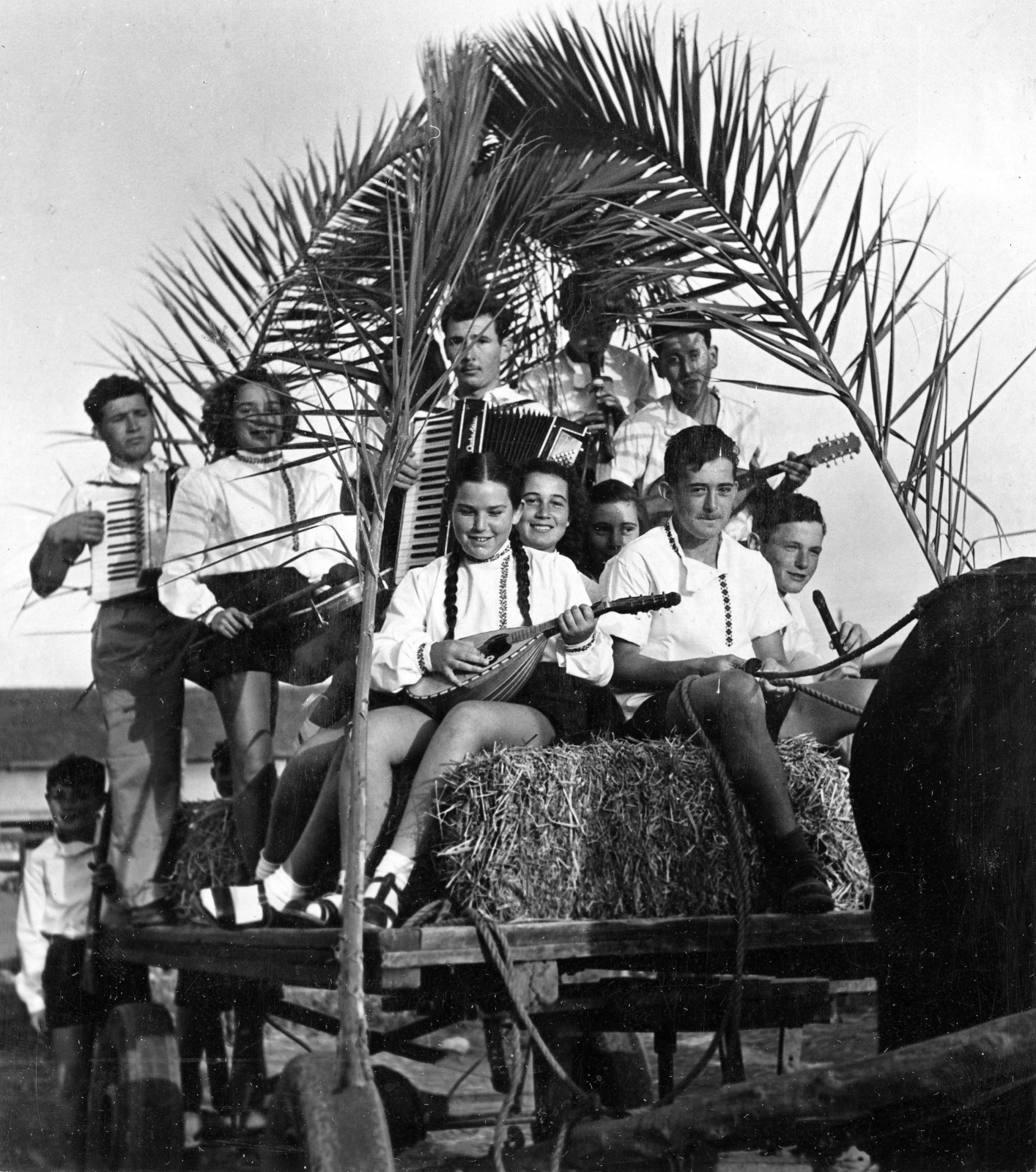

On Shavuot, kibbutzim used decorated wagons and staged pageants to showcase the year’s achievements in the fields, as well as new machinery and even new babies.

But it was the city of Haifa that adopted Shavuot as its own city-wide celebration.

The first municipal pre-state celebration of Shavuot was held in Jaffa, in 1912. According to researchers Yair Safran and Dr. Tamir Goren, it was not a harvest celebration but rather a “Flower Festival” in which houses were bedecked with garlands, and women and children wore flowered wreaths.

At that time, the kibbutzim held individual celebrations; it was only in the early 1920s that these celebrations began to coalesce into one joint celebration at Ein Harod.

But in the late 1920s, the city of Haifa was becoming the locus of the region, as a port city, railway depot and center of industry. (The popular saying, still in use today: “Haifa works, Tel Aviv plays, Jerusalem prays.”)

In 1930, Haifa held its first official Bikurim celebration. Crowds gathered in the original Technion courtyard (now part of the MadaTech National Museum of Science, Technology and Space) to see an exhibit of products from nearby Kibbutz Yagur, Shemen Industries, Palestine Flour Mills and more — and to enjoy performances by a children’s choir and the Hapoel Orchestra.

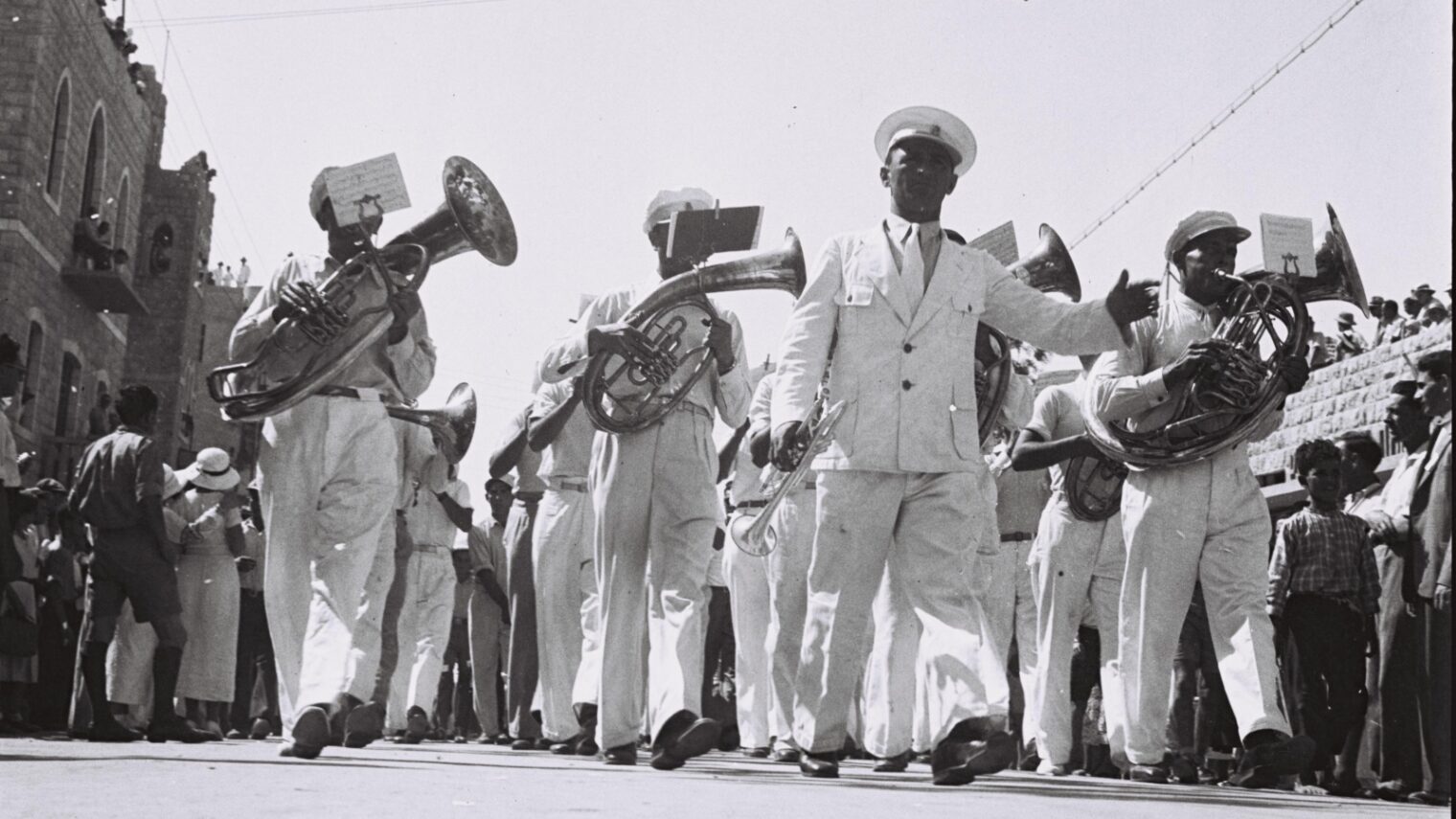

The following year, the celebration was geared toward the city’s children, beginning with a ceremony of first fruits in the Technion courtyard, a parade of schoolchildren waving banners and marching down the streets of the Hadar HaCarmel neighborhood, accompanied by the Hapoel trumpet band, followed by a play at the Haifa amphitheater.

Considering these successful events, in 1932 the Hadar HaCarmel Committee decided to expand the format and bring all the small northern region celebrations under one roof.

Safran and Goren write, “They issued a series of posters, and sent emissaries with letters of invitation to all the communities. The [agricultural] settlements were invited to present their work at a joint event described as ‘An Israeli style celebration and an expression of renewed Hebrew agriculture.'” A dove of peace logo was designed for the event.

The organizers emphasized that this event would bring tourists from all over to Haifa and the Galilee and put a spotlight on what they felt was an overlooked city. The committee further stressed that the event would not become a raging Tel Aviv-style Adloyada Purim street party.

And indeed, the 1932 event featured dignitaries such as Dr. Shmaryahu Levin, one of the heads of the World Zionist Organization and Keren Hayesod, as well as an early proponent of the Technion, and Jewish National Fund president Menachem Ussishkin.

The opening event’s artistic program included the HaOhel theater company, the Orenstein Sisters dance troupe, the Haifa Workers Choir together with the HaZamir choir, and an athletic demonstration put on by the city’s sports organization.

The next morning, the schoolchildren’s procession through Hadar HaCarmel was followed by an exhibit at the Hebrew Reali School entitled “Haifa – The City of the Future” (the name was a nod to Herzl’s vision for the port city).

The Technion hosted an exhibition of local “Land of Israel” artists that included works by names that would become famous like Joseph (Yossef) Zaritsky, Avigdor Steimatzky, Nahum Gutman and others. Lectures on the topics of Haifa and the achievements of the Jewish settlement there, were given throughout the city, along with tours of Haifa and Mount Carmel. In the evening, the Maccabi Auditorium hosted not one but two dance parties.

The next day, Safran and Goren relate, Tel Aviv-based Doar HaYom newspaper mocked the Haifa locale, the event itself and the logo. “The dove — symbol of the Bikurim holiday — [the writer] compared to a parrot which, in his opinion, expressed the desire of the people of Haifa to imitate Tel Aviv.”

There was also some blowback concerning the preponderance of red flags, as opposed to blue-and-white ones, due to the dominance of the Histadtrut (National Workers’ Union) in Haifa.

The Haifa rabbinate was concerned about desecration of the holiday, requesting of the committee in advance of the 1933 event that the celebration not be called “Bikurim,” as this ceremony was meant to be confined to the Holy Temple, which had been destroyed in antiquity and was not yet rebuilt.

Taking these concerns to heart, the 1933 Shavuot event took place at the end of the holiday. It opened with a three-act play by poet Avraham Shlonsky; an imagined reenactment of the pilgrimage to biblical Jerusalem and the first fruits ceremony at the Temple Mount.

The following morning, 500 people marched in the Hadar HaCarmel parade to the Technion to enjoy poetry and song. The Hadar HaCarmel market was inaugurated during the celebration, fittingly with actual first fruits of the season. Sailing races were held on Saturday, and the weekend closed with fireworks.

The Tel Aviv-based media, once again, could not help but add a dose of snark. Writing in Ha’aretz, poet Natan Alterman, described at length the beauty of the holiday and the city but also noted that the Haifa event was lacking “the joy of the Adloyada.”

Nonetheless, Bikurim had raised the city’s profile. The celebration reached a high point in 1934, with a guest list that included Sir Alfred Mond (Lord Melchett), Haifa Mayor Hassan Shukri, electric company founder Pinchas Ruttenberg, Ussishkin and many other representatives of the Zionist movement and the British Mandate. The JNF-KKL, which had taken a more central role in the celebration, documented that year’s Bikurim in a unique film.

The Shavuot holiday of 1935 fell on a Sabbath, causing a rift between Haifa’s secular and religious populations and, in the end, the festivities did not take place that year. Nor was there cause for celebration the following year due to the Arab riots of 1936.

There were small local celebrations in 1937 and 1938, but these too faded by 1939, with the advent of the Second World War. After the establishment of the State of Israel, the JNF-KKL would host its Bikurim ceremonies at its headquarters in Jerusalem.

As for the kibbutzim — which lived the agricultural calendar in very real way — they continued to celebrate the Shavuot harvest with processions and pageants and do so till this very day.

![Elections 1977 – Likud posters] In 1977, Menahem Begin led an election upset as Israel’s first non-Labor prime minister. Credit: GPO Elections 1977 – Likud posters] In 1977, Menahem Begin led an election upset as Israel’s first non-Labor prime minister. Credit: GPO](https://static.israel21c.org/www/uploads/2019/09/Elections_1977___Likud_posters_-_GPO-768x432.jpg)