October 7 made both Jewish and Arab Israelis jittery. Aside from pain and shock, many wondered how the massacre would impact relations between them.

For conflict-resolution activist Mohammad Darawshe, decades of bridge-building between the two populations was put into jeopardy overnight.

“There were daily calls by Hamas to Arab citizens to create another front by joining the war. The environment was ripe with problems and I knew we had to prevent escalation,” he tells ISRAEL21c.

Surveys confirmed what was already clearly apparent to Darawshe, who lives in the Galilean town of Iksal with his wife and four adult children. Mutual mistrust was soaring amongst Jews towards Arabs (from 50 percent in regular times to 81%) and in reverse from 24% to 52%.

The Director of Strategy at Givat Haviva’s Center for Shared Society, Darawshe quickly mobilized local and national Arab leaders to convey to their populations they did not want to be part of this war.

They got Jewish and Arab mayors of neighboring towns and villages to issue joint statements encouraging good relations between communities.

The outcome was a “collective decision by Arab citizens that what happened on October 7 does not represent us. An understanding that at the end of the day, when this war is over, we’re going to stay Israeli citizens. What we do now will reflect on our relationship with our fellow Jewish citizens tomorrow.”

Offering a warm haven for the displaced

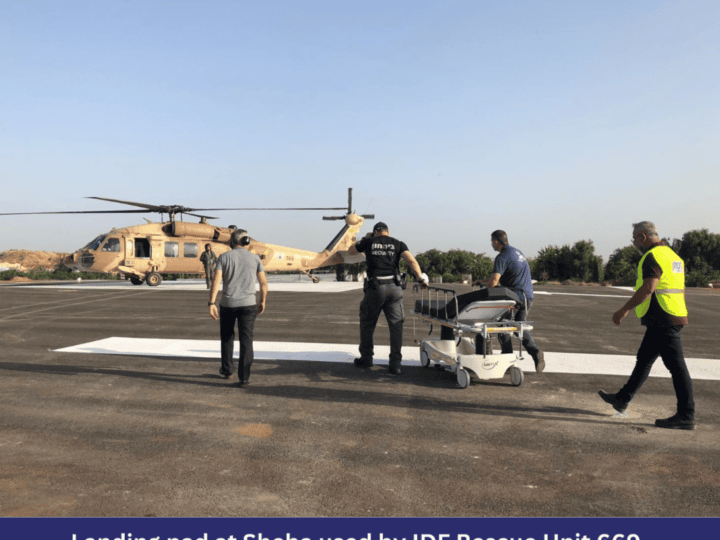

The other swift action taken by Givat Haviva was to give immediate refuge for the first two months of the war to more than 300 displaced residents mostly from Ashkelon in the south.

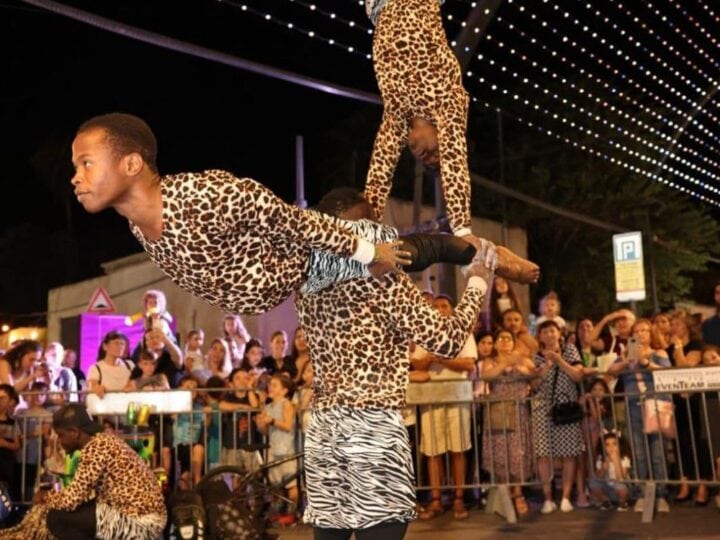

A mental health center staffed by volunteer clinical psychologists who specialize in trauma treatment was set up and the campus’ Shared Arts Center hosted daily workshops facilitated by art therapists and leaders.

To create a warm, supportive community in which evacuees would feel valued and significant, committees were set up in which family representatives could actively participate in planning programs and activities.

Children were enrolled in local schools selected to align with their backgrounds and afterschool clubs were established. Youth counselors organized evening activities for teens.

Most of this activity ended in December when the evacuees returned to Ashkelon.

Public to private pain

Throughout this difficult period, the Darawshe family was also dealing with their own personal tragedy from the Hamas attack.

Awad Darawshe, a 23-year-old cousin who worked as a United Hatzalah paramedic, was murdered by Hamas as he tried to treat injured partygoers at the Supernova music festival.

“He thought in selflessness. He didn’t care about the culture, identity or ethnicity of the people he was treating,” Darawshe told reporters at the time. “On the contrary, he thought because he had a different ethnicity, he could probably save them because he spoke Arabic and he wanted to save the Jewish and international kids there.”

Shared society, shared future

Givat Haviva was founded in 1949 by the Kibbutz Federation as a nonprofit organization to create mutual responsibility, civic equality and cooperation between divided groups in Israel.

Its Center for a Shared Society has a 40-acre campus in the north where education, language instruction, culture and art are used to empower and bring Arabs and Jews together.

Darawshe joined in 2000 after leaving his role as campaign manager for the Democratic Arab Party and later the United Arab List (RAM).

He has been committed ever since to building up Givat Haviva’s programs and 2024 was supposed to have a record enrollment of 3,000 Jewish and Arab youth participating in joint programs around the country.

Although the Hamas attack and ensuing war made it impossible to form new groups, many of the existing ones resumed within a month. It was a relief to Darawshe, who is a staunch believer in continuity: “The impact of one-time programs evaporate with ‘returning home syndrome’ that pulls you right back into stereotypical thinking.”

Stereotypes are easy to fall back on here, he says, due to the ongoing conflict which “keeps beaming negativity” and the fact of limited interaction between the two sectors of society – 92% of Arab citizens live in separate towns and villages and the 8% in mixed cities usually live in separate neighborhoods.

As a consequence, education is separated too, with only eight mixed schools around the country.

Darawshe’s solution is to bring Arab teachers into Jewish schools and Jewish teachers into Arab schools. Today there are 2,500 teachers in the program, which he considers one of the best projects in coexistence today.

“It can change a whole school culture. If you have an Arab teacher in a Jewish teachers’ lounge they probably will not be making jokes about Arabs, at least not nasty ones. The presence of a Jewish teacher in an Arab teacher’s lounge changes the discourse about how you talk about Jews.”

Social interaction and cultural exploration also come about as they discover each other’s religious holiday in real time.

No hummus coexistence

Darawshe, who has an MA degree in peace studies and conflict management from Haifa University and worked previously as co-director of The Abraham Initiatives, says the way to build a shared society is not about meetings based on “hummus coexistence where you eat hummus, enjoy each other’s company and go home. These [meetings] fake equality and avoid talking about the problems.”

At the same time, getting involved immediately in the narrative debate is also not conducive to building bonds as “it starts a ping pong blame game.”

The best way to build connection, he says, is to start off understanding mutual interests and that “we live in the same country, we share the same buses and shopping malls.”

He notes “islands of success in Jewish-Arab relations” including the fact that one-third of the medical sector in Israel today is Arab.

The mentor who set him on his path

It was the late Emile Shouafani, organizer of the first Jewish-Arab group to Auschwitz-Birkenau, who set Darawshe on his path at age 16.

As his teacher at the Nazareth High School Darawshe attended, Shouafani suggested he take part in programs for Jewish and Arab youth at Givat Haviva.

“I went to Muslim elementary school, Catholic high school, Hebrew University. I learned Christianity from Christians, Judaism from Jews, Islam from Muslims. It gives you the real sense of what another culture is and not a stereotypical sense. Diversity in education is also a wonderful way to get a well-rounded perspective of life,” he reflects.