“Adloyada” is a contraction of the phrase “ad lo yada” or “unable to differentiate,” referring to the Purim tradition of drinking into oblivion. Adloyada is also the name of the historic Purim parade that originated in 1900s Tel Aviv and helped to cement that city’s reputation as Party Central.

The first Purim parade was instituted in March 1912 by Avraham Aldema, a painting teacher at the Herzliya Gymnasium high school. It featured costumes based on themes from the Megillah (the Purim story), the Bible, Jewish history and life in the Land of Israel.

The procession marched from the gymnasium down to the railroad track on Herzl Street, accompanied by a band of merrymaking young people, workers and artists that included Aldema, known as Hevre Trask (“noisy folks” as “trask” means “crash” in Yiddish).

Meir Dizengoff, then head of the Tel Aviv’s founding Ahuzat Bayit society (and eventually the first mayor after Tel Aviv received township status), decided that the parade should become an annual event. A committee was formed to select a name for the Purim carnival and 253 names were submitted from locals and outsiders.

The name chosen, “Adloyada,” was offered by the poet, author and newsman Isaac Dov Berkowitz who based it on an excerpt from the Babylonian Talmud stating that on Purim, one must drink wine until one does not know the difference between accursed Haman and blessed Mordechai.

It was also in the 1920s that dancer-choreographer-artist and Tel Aviv’s original man-about-town, Baruch Agadati, became involved in the festivities, organizing an annual Purim ball and instituting the Purim Queen pageant. (Read here

about the Yemenite milkmaid who became 1928’s Purim Queen.)

The competition between the celebrations — and the fact that Agadati wore fine clothes and charged entrance fees to his parties – led to a not-so-friendly rivalry between the bon vivant and the bohemians. Hevre Trask made their feelings known in print, leading to a lawsuit filed by Agadati charging Trask with defamation of character.

Initially, the Purim parades were sponsored by the Jewish Workers’ Fund of the Mapai (Labor) Party (from 1921-1925) and then by the Jewish National Fund (from 1925-1928), after which Aldema turned to the municipality for funding. The procession of 1929 was jointly sponsored by the JNF and the municipality. In 1930, there was no Purim procession following the riots and massacres of 1929.

In 1931, the Tel Aviv Municipality took over the Purim parade that was officially named “Adloyada” in 1932.

According to a Tel Aviv Municipal Archive essay, a special committee of artists, writers, architects and theater people was formed “to give the Adloyada processions historical content and a worthy artistic level.” Among the topics selected were “settlement, construction, agriculture, testimony, immigration and even the rise of anti-Semitism in Europe.”

As part of the Purim events, the city’s houses and vehicles were decorated with flowers, carpets and flags, and colorful lighting was installed. Marchers were guided by director Moshe Halevi and musician Menashe Rabina, with decorations around the city by leading artists like Nahum Gutman and Reuven Rubin.

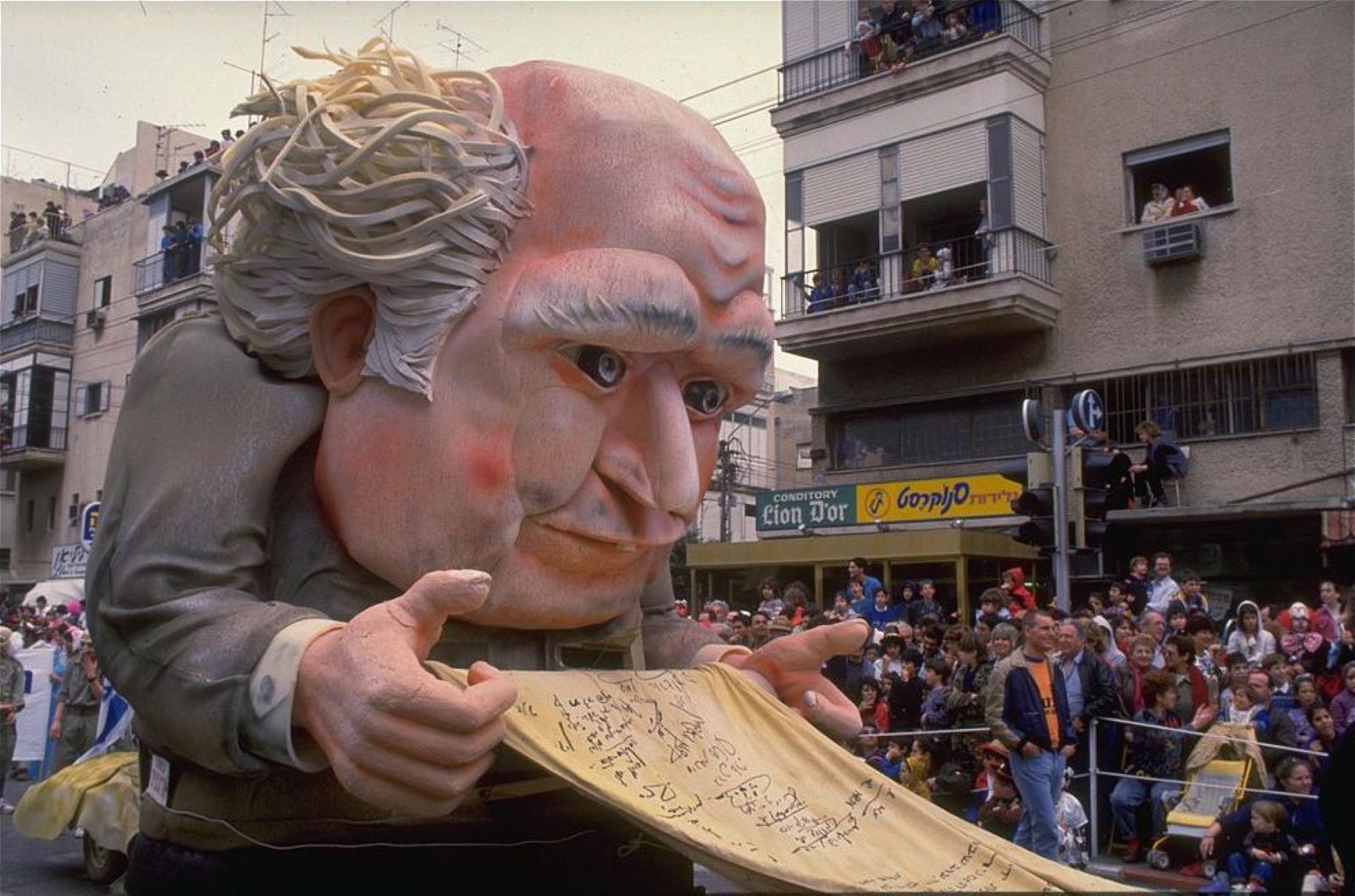

The parade never shied away from current politics, represented in floats like the one in 1926 that buried the British Mandate in a coffin, the 1933 float of Hitler holding a lance aloft before two corpses with the sign “Death to All Jews,” the three-headed dragon representing the Nazi regime in 1934, or the 1935 anti-profiteering crocodile.

Interestingly, in 1933, the German Consulate in Jerusalem wrote to the mayor of Tel Aviv demanding an apology but Dizengoff refused, reportedly responding that it was amazing the critique wasn’t stronger.

The Adloyada came to an end in 1936. As the Tel Aviv Municipal Archive essay speculates, “The official reason given was the difficult situation of German Jewry and of Central and Eastern European Jewry, as well as [curfew] decrees by the British Mandatory authorities. It is also possible that budgetary difficulties and illness and death of Dizengoff in 1936 caused a stop to the processions.”

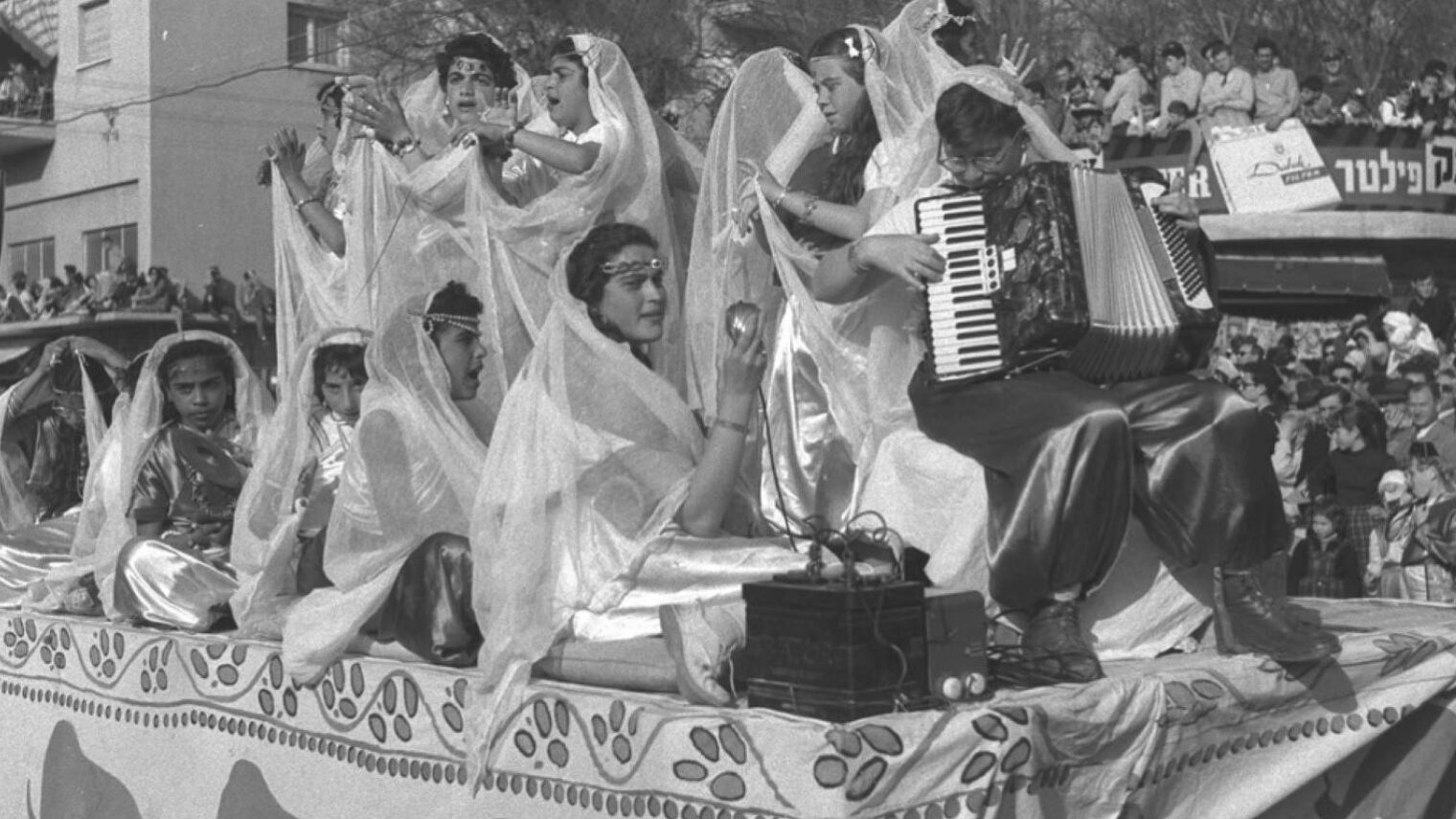

Following the establishment of the State of Israel, the Adloyada tradition was renewed and Tel Aviv hosted the parade from 1955 through the late 1960s. The parade was transferred to Holon in the 1970s.

In the early 1980s, the Tel Aviv Adloyada tradition was revived by the Sheinkin Street avant garde. The tone was far more in the spirit of Hevre Trask: a punk rock/performance art street fair that went on for days. But, like the fast and furious music that inspired it, the Sheinkin Adloyada bacchanal came and went.

In 1998, a one-time Adloyada was held in Tel Aviv that was documented in a video that jokingly opened with the line: “The Last Tel Aviv Adloyada – 1998. The next Tel Aviv Adloyada will probably be in 2228”

Today, the word coined by Isaac Dov Berkowitz, “Adloyada,” has come to mean any Purim parade held in towns across Israel.