Imagine getting an email or a phone call out of the blue, telling you of a potential windfall worth 250,000 shekels ($67,000).

Ancestors you never knew bought shares in an early Zionist fundraising project well over a century ago.

The money was never spent and has been gathering dust – and interest – ever since in a bank account you knew nothing about.

Researchers working for the Israeli government are now busy tracing descendants of these investors – in some cases their great-great-great grandchildren – and you might be one of them.

A dedicated team at the Guardian General’s office, part of Israel’s Ministry of Justice, is doing everything it can to give the investors’ heirs what’s rightfully theirs.

“As far as I know – and we should be proud of this – Israel is the only country in the world which actively looks for those with rights in abandoned and unclaimed property,” says Jonathan Kirsch, department head in the unit for the location and restitution of unclaimed property.

“Everywhere else in the world, information is published, it’s advertised in official places, but there’s nobody actually actively looking for the rightful owners.”

Reactions vary widely, he says when they finally contact the heirs of the original investors and say they may have money for them. Some are delighted, others think it’s a scam.

“These are total stereotypes,” he says, “but Americans are very, very suspicious, Israelis are quite happy to cooperate, and Brits say thank you very much. We greatly appreciate your calling. We’d be happy to receive any details you can send and we’ll get back to you.”

Forgotten shares

The story of the unclaimed shares began when Theodor Herzl, father of modern political Zionism, realized he’d need hard cash to turn the dream of a Jewish homeland into reality.

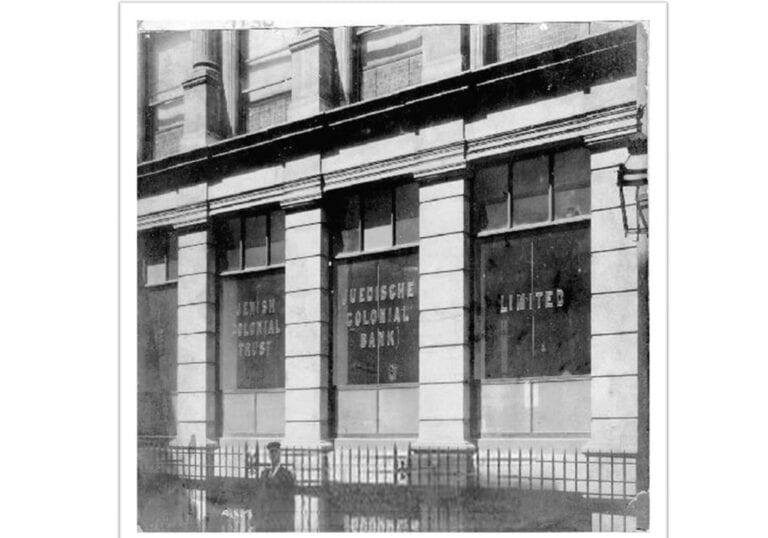

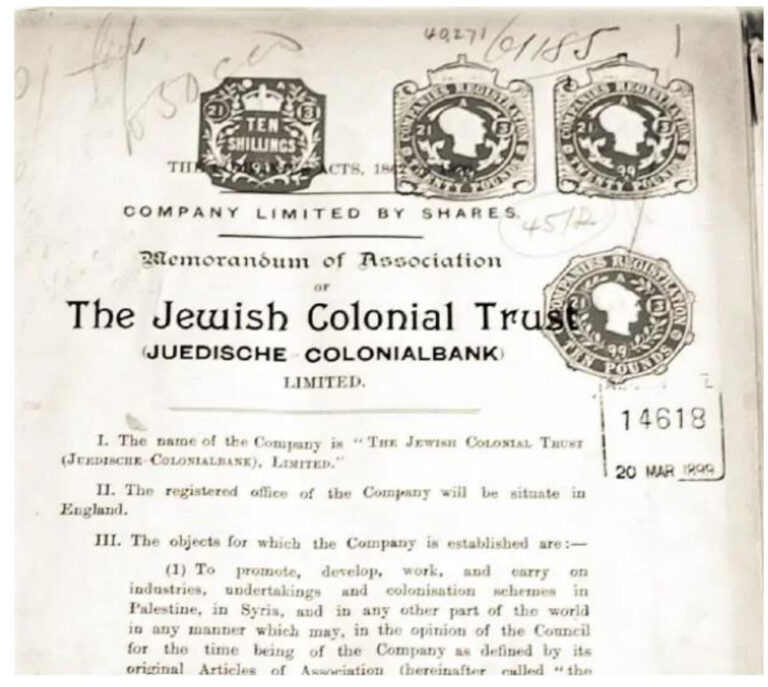

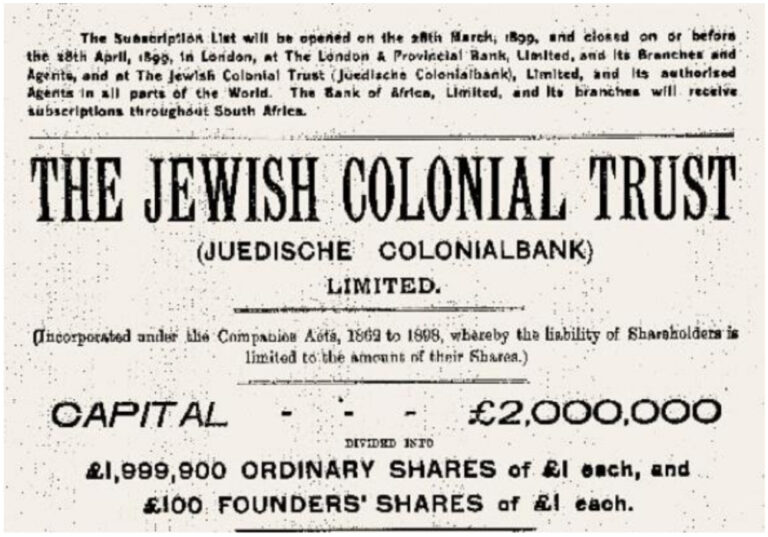

The Jewish Colonial Trust (JCT) was established in London in March 1899 (when the word “colonial” didn’t carry today’s negative connotations).

It initially issued 250,000 shares at £1 each (£157 or $196 in today’s money) so that people could invest in buying land from the Ottomans, who then ruled Palestine, for Jewish farming and commerce projects.

It wasn’t quite the success Herzl had hoped for. He bought 1,000 shares – a substantial investment at the time – but the scheme fell far short of its 2 million target and much of the money was never spent.

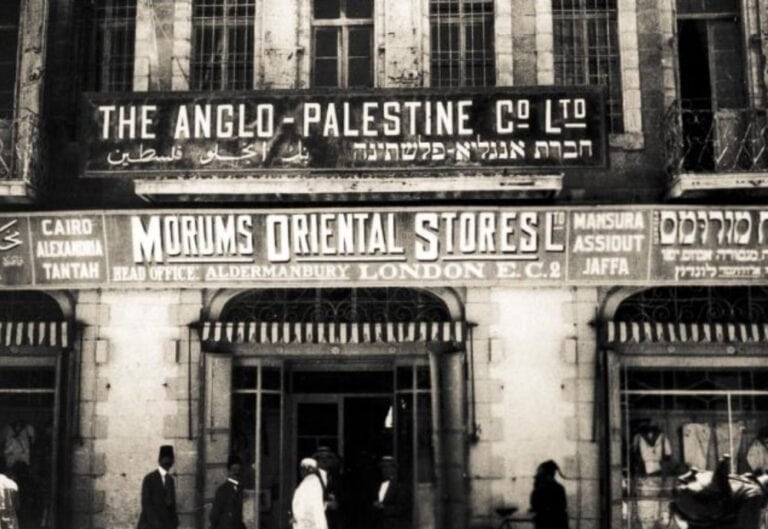

In time, the JCT shares were transferred to the Anglo-Palestine Bank (which became today’s Bank Leumi) and were largely forgotten.

Fast forward to today, and the government, which already tracks down the owners of unclaimed land and property, is now actively chasing the descendants of those early Zionist investors from 125 years ago.

It’s a daunting task. The ultimate aim is to find heirs to around 180,000 named shares, worth $124 million, which originally belonged to 80,000 named shareholders.

Detective work

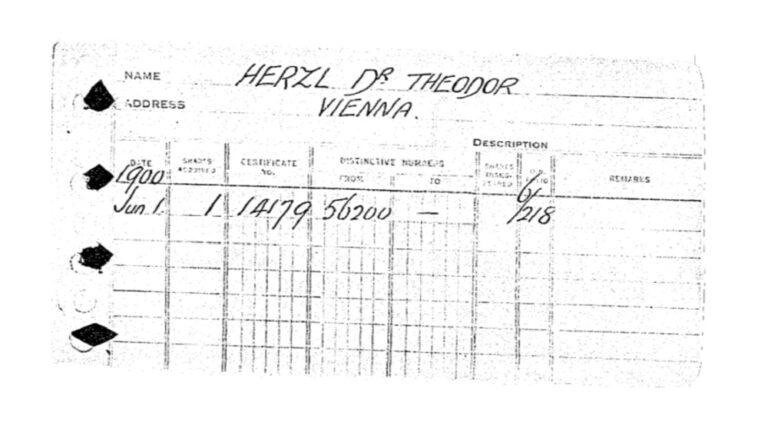

The team has an old-style “database” of records cards, salvaged from the JCT’s London headquarters after the building was bombed by the Nazis during World War II. The challenge is to find their descendants.

There’s a lot of detective work involved, a lot of family trees to be drawn, and a lot of probate records to be trawled.

Most of the actual certificates have been cashed in, lost or destroyed over the years, and many of the investors and their descendants perished in the Holocaust (60 percent of JCT shares were sold in Eastern Europe and are dealt with by a department dedicated to Holocaust victims’ assets).

But that doesn’t affect the heirs’ claims, as long as the heirs have the documentation to prove who they are.

At present, the small team of Sherut Leumi (National Service) workers are concentrating their efforts on identifying heirs to the bigger investors – those who bought 100 shares or more – but the aim is to reach everyone eventually.

“When we do track down an heir, we explain that we have a legal duty to locate people with unclaimed property,” says Kirsch.

He acknowledges that people can be suspicious. “Only today I received a letter from somebody saying they’d been contacted, and they were worried it was a phishing scam.”

Flea market find

Anyone who finds a share certificate in their attic can contact Kirsch and his team to see if it can be redeemed.

The “named shares” will require proof of ID. The “bearer shares” – essentially blank checks – can simply be cashed in.

“One guy told us he bought a wardrobe in a Tel Aviv flea market,” says Kirsch. “He opened the drawer and found 20 bearer share certificates, so that was a nice 50,000 shekels for him.”

“Americans are very, very suspicious, Israelis are quite happy to cooperate, and Brits say thank you very much.”

An elderly gentleman from Kibbutz Tzora, outside Jerusalem, turned up with a single share certificate, a wedding gift from his parents-in-law 60 years ago. It matched the record card, so he got his 2,500 shekels.

The team tracked down an heir to 25 shares from Manchester, England. To prove the claim, they found his ancestor’s naturalization papers, dated 1910, and discovered they’d been signed by Winston Churchill, as Home Secretary before he became British Prime Minister.

Reuniting families

Kirsch related the story in a Zoom meeting to publicize his work during the Covid pandemic, and chanced upon more family members, who also got a payout.

“We end up reuniting families,” he says. “We reach relatives all over the world and then, as long as they’re happy to do so, we put them in contact with each other.

“Many of them say it’s not so much the money, it’s the fact that they’re able to get together as a family.”

It’s a big task, matching all this money to all those heirs. Will they ever finish the job?

“Yes, certainly the large amounts that we’ve been talking about,” says Kirsch.

“I expect within a couple of years, we will have dealt with all of those.

“The small amounts technically could go on forever, but there’s no closing date. We’re happy doing what we’re doing and we feel there’s real meaning to our work.”

Click here for the Guardian General and Director of Inheritance Affairs website or email jct@justice.gov.il.