Despite being buried under a mound of cheese in recent years, Shavuot, the Feast of Weeks, is not a holiday celebrating lactose tolerance. It is actually a harvest holiday commemorating bikkurim — the biblical custom of bringing offerings to the Holy Temple in Jerusalem comprising the Seven Species of the Land of Israel: wheat, barley, grapes, figs, pomegranates, olives, and dates.

Shavuot is also the holiday of the giving of the Torah to the Jewish people at Mt. Sinai; this tradition became central to Jews in the Diaspora who could not celebrate Shavuot as an agrarian holiday. With the renewal of Jewish settlement of the Land of Israel, as the Ministry of Tourism puts it, “the new farmers (mainly in the kibbutz and moshav cooperative farming communities) reinstated the agricultural aspect as the main focus of the holiday, and a rich and colorful tradition developed around ceremonies commemorating the bringing of bikkurim“.

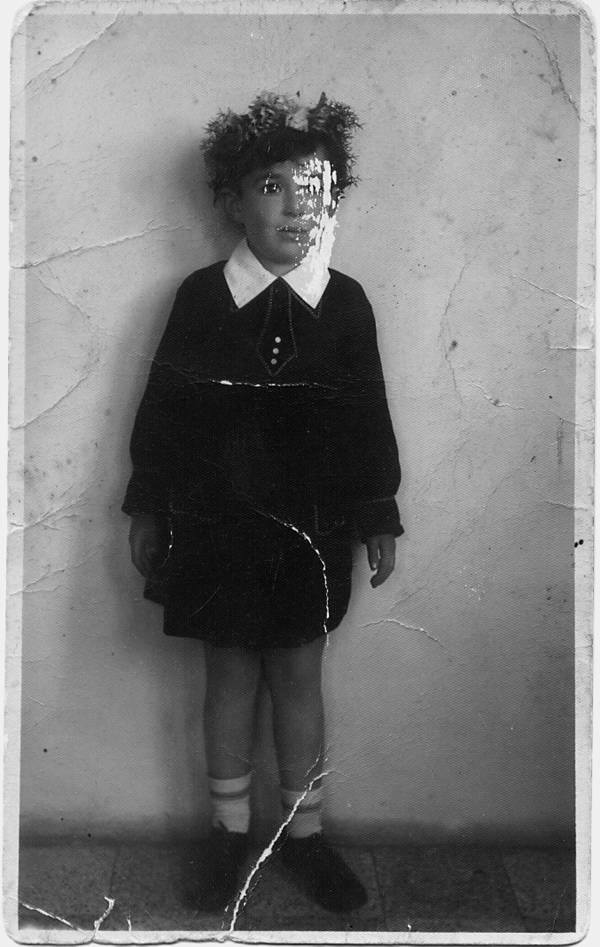

From early on, the kibbutzim and moshavim instated secular ceremonies: parades of wagons (and later tractors and other agricultural machinery) bearing the fruits of the fields. That bounty also included the most precious crop: children dressed in festive spring attire, heads festooned with garlands of flowers.

However, flower garlands are not unique to Shavuot, and head wreaths, in fact, for many cultures have been a symbol of harvest bounty and, by extension, female fertility since time immemorial. According to an article in Vogue magazine, The History of Flower Crowns and the Women Who Wore Them: From Frida Kahlo to Kate Moss, author Laird Borrelli-Persson writes, “In agrarian societies, tied to the land and the seasons, flower crowns had great symbolic meaning. Worn for practical and ceremonial reasons, they could illustrate status and accomplishment (Olympic olive wreaths)”.

“The language of flowers and herbs was well-known, with each carrying its own meaning… Full of significance, floral headdresses were woven into the social and dress traditions of places as distant as Russia and Hawaii”.

“May Day, an ancient celebration of spring, adapted from ancient civilizations in medieval times, remains an occasion on which floral crowns are worn”.

It’s possible that Jewish settlers from eastern Europe reintroduced the harvest flower crown to the Land of Israel, having been influenced by Slavic neo-pagan fertility symbols like the Ukrainian wreath (shown above), a tradition that possibly dates back to per-Christianity, and which definitely gained popularity with the rise of nationalism in Europe in the 19th century.

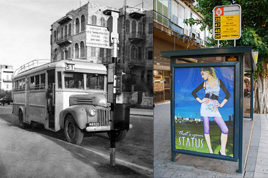

Fashion and culture blogger Ayala Raz relates that in its early years, the city of Tel Aviv attempted to link its name — which means “Hill of Spring –with Shavuot, establishing a “Holiday of Flowers” on Shavuot in 1912. “On this holiday, all the city’s houses were decorated with flowers, schoolchildren marched in parades with garlands on their heads, and funds were raised for the needy by selling floral boutonnieres on the street to be worn on the lapel”.

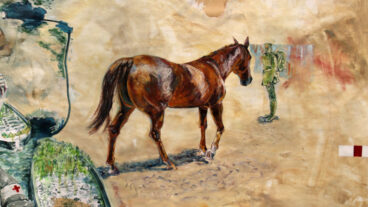

“Tel Aviv celebrated the Holiday of Flowers once again in 1914, holding a floral procession led by girls dressed in white and adorned with flowers, followed by marching boys leading an ox with a wreath on his head, and some boys carrying goat kids and lambs on their shoulders. It was the Flower Holiday combined with a reconstruction of the pilgrimage to the Holy Temple”.

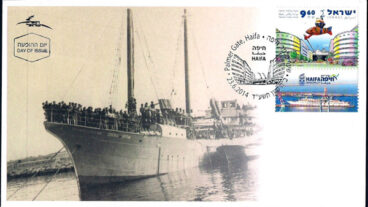

“During World War I, Tel Aviv’s residents were expelled from their homes [by the Turks] and the city abandoned, but immediately upon their return in 1918, they celebrated the Holiday of Flowers again at Shavuot. They also brought back to the city the Torah scrolls that they had taken with them during the deportation”.

“A short time later, a debate arose in the city between religious and secular about the proper timing for the Holiday of Flowers. The religious faction claimed that the holiday of Shavuot was about being given the Torah and not a flower festival. As an attempted compromise, in 1920 the Holiday of Flowers was scheduled for celebration together with Tu b’Shvat, but due to difficulties in obtaining a parade license, the Tu b’Shvat planting ritual was celebrated at Mikve Israel, while the Holiday of Flowers was put off until the Purim holiday.

“However, the Tel Hai riots fell on Purim that year, and mourning within the Jewish settlement in their wake caused another delay. And so, despite religious opposition, the Holiday of Flowers was once again celebrated in Tel Aviv at Shavuot”.

“In the 1920s, the tradition of holding the Holiday of Flowers at Shavuot was cancelled, and the tradition of celebrating Shavuot as the holiday of bikkurim was revived”.

Needless to say, flower crowns have persisted over the decades as a holiday motif.

Interestingly, Israel is the only country where flower garlands are also worn by children on their birthday, and almost every native-born sabra has memories of having to wear a scratchy headdress at their kindergarten party.

Photo credits: Ayala Raz, Central Zionist Archives, Kibbutz Ein Shemer, Nostal.co.il, Rachel Neiman, Wikipedia. Photo of my mother, Shulamith Dubno-Neiman at age 3 or 4 (1932 or 33) – photographer unknown.