“We have a responsibility to document societies that have yet to become modernized before they disappear,” says Golan Levi, user experience expert at the Israeli online genealogy platform MyHeritage.

“Complete cultures are being lost.Our line of work involves researching family history and we are at a stage where we can give back to society – it’s our responsibility,” he tells ISRAEL21c.

“We all want to know where we come from; we value our heritage. But I know nothing about my grandfather’s life as a child in Iraq, for example. Now we have the ability to document such information for the sake of the future generations. That’s the main motivation.”

Levi heads Tribal Quest, a pro-bono project sponsored by MyHeritage.

Founded in 2003 by Israeli entrepreneur Gilad Japhet from his living room in Moshav Bnei Atarot, the company now has over 92 million users worldwide and supports 42 languages.

MyHeritage, which also runs a program to match descendants of Holocaust survivors with property taken from their family, ranked sixth on the business newspaper Calcalist’s list of most promising Israeli startups in 2018.

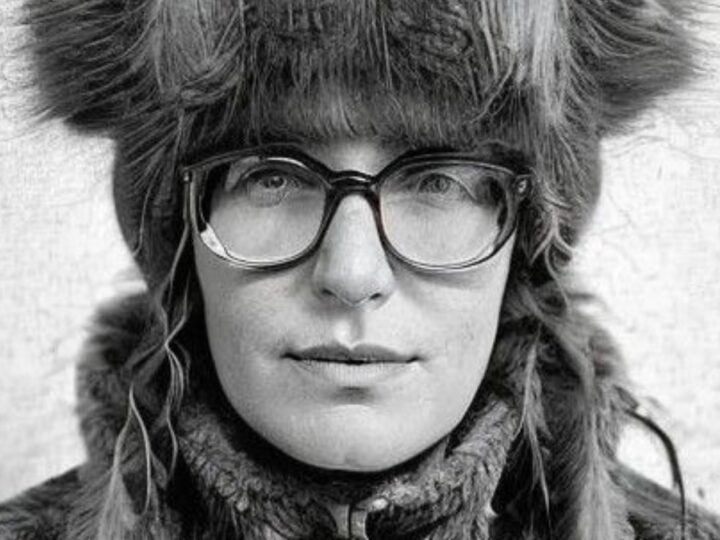

Levi recently returned from a groundbreaking expedition to Panama and Ecuador. He previously led three-week Tribal Quest missions to interact with the Himba people in Namibia, five distinct tribes in Papua New-Guinea, and the Nenets nomadic reindeer herders in Siberia.

He had already herded reindeer, hunted crocodiles and eaten grubs. “Those first three journeys were profound experiences filled with stories about human traditions, behaviors and beliefs,” Levi recounts.

“The recent expedition to Panama and Ecuador was more complicated logistically. It was demanding on many levels – physically, emotionally and spiritually.”

Of the six team members, all Israelis from different departments in the company, only Shahar Bitton had experience from the previous journeys.

“It was different from anything they’d done in their lives– for a marketing person to interact with people from such a different background, attentiveness and empathy are key.”

The team, plus a translator-guide and videographer, flew to Panama where they met with four distinct tribes: the Embera, Ngobe, Naso and Guna.

Then they ventured deep into the Amazon rainforest, flying from Quito in rickety four-seater airplanes over the broccoli-like rainforest to a remote grassy airstrip where they met the Achuar people of Ecuador, who have thrived there for thousands of years.

About 8,000 Achuar live in 86 remote communities along the border with Peru. “They were as curious about us as we were about them,” Levi says.

“The Achuar have always been self-sufficient hunter-gatherers and small-scale farmers,” he explains. “They are the indigenous population and have a strong spiritual connection with nature based on maintaining equilibrium and harmony with the forest that surrounds them. The forest is interwoven with their culture. They are the forest’s greatest protectors.”

Like opening a time capsule

“The main aim of this project is to preserve their culture and family history so that their great-grandchildren will know where they come from,” says Yoel Corcias, the expedition’s technical support engineer.

“Imagine a descendent of these people living in an urban environment 100 years from now discovers this time capsule. We are creating future treasures.”

There is also a structured phase in which they gather families together and try to build family trees.

“Our clear preference is to meet with people in their own environment where they can express themselves freely,” Levi explains. “We asked them about their reality, gave them an empty canvas. Trust is a major issue – we demonstrate our sincere intent by sleeping and eating with the people. We immerse ourselves into the situation and try to understand their perspective.”

As well as the visual documentation, Levi’s team took Polaroid photos to give them. “It works like magic every time. It’s easiest to communicate with the children. The adults usually take longer to drop their defenses, but if we peel away the layers carefully, we can communicate peacefully. It takes time for people to let their guard down and feel comfortable with strangers.”

The Achuar showed them how they cook, pray, weave their intricate baskets, varnish their clay bowls, and make garments and weapons using indigenous materials.

“There’s a strong family emphasis, with a morning ceremony in which they together decide the agenda for the day,” Levi notes.

“We’re not anthropologists coming to make observations,” he emphasizes. “That’s not our role.”

At the core, we are the same

It is sometimes difficult not to be judgmental, Levi admits.

For example, they witnessed how the women prepare the traditional Chicha drink – by regurgitating a woody shrub into a vat of fermenting maize, an abhorrent sight to Western eyes. In general, women’s roles hardly match modern Western standards.

They also joined a fishing expedition, where complete families participated in the local practice of damming a river with branches lashed together by vines and releasing a natural plant-based toxin into the water that closes fishes’ gills so they float into the dam.

“It demonstrated the solidarity of the community,” notes Levi. “Every person had a defined role.”

The MyHeritage team found the expedition emotionally and physically demanding, dealing with new situations ranging from unusual dietary conditions todrenching humidity.

“The people that we’ve met live in such different circumstances. But what strikes me most is that at the core we are completely the same – we share the same passions, fears and basic instincts. This I find heartwarming,” says Levi.

Insights from the journey

In contrast to Panama, where indigenous cultures are already transformed by tourism, Levi says the Achuar are steadfast in wanting to remain in rainforest communities accessible only by small planes and canoes.

“But they do not reject modernization outright – for example, their canoes are motorized. Some of the younger generation speak passable English and they understand the importance of communication with external forces. They are desperately trying to defend their territory against the penetration of giant oil companies.”

Golan admired the Achuars’ sense of community.

“They do many things as a collective and every community has a main communal structure. Their communal assemblies look like chaos to the outsider– everyone talks at the same time and they avoid eye contact, but there’s order to their chaos. For them it works. It’s very refreshing to see, something we lost a long time ago.

“They are hard-working, positive, happy people who know how to collaborate. They know the secrets of the forest better than anyone else. We have much to learn from them.”