Jerusalem – as any resident or visitor will attest – is home to many cats. And while debate rages over the good and evil of Jerusalem’s ubiquitous strays, another proud member of the feline family is even more visible to those with an attentive eye: the Jerusalem lion.

On every street, in parks and porticos, on garbage cans and swaying in the breeze atop steely flagpoles, lions quietly watch over Israel’s capital.

The most prominent and oft-spotted cat is the Lion of Judah, standing erect on back paws in the insignia of the Jerusalem municipality, which adopted the symbol in 1950.

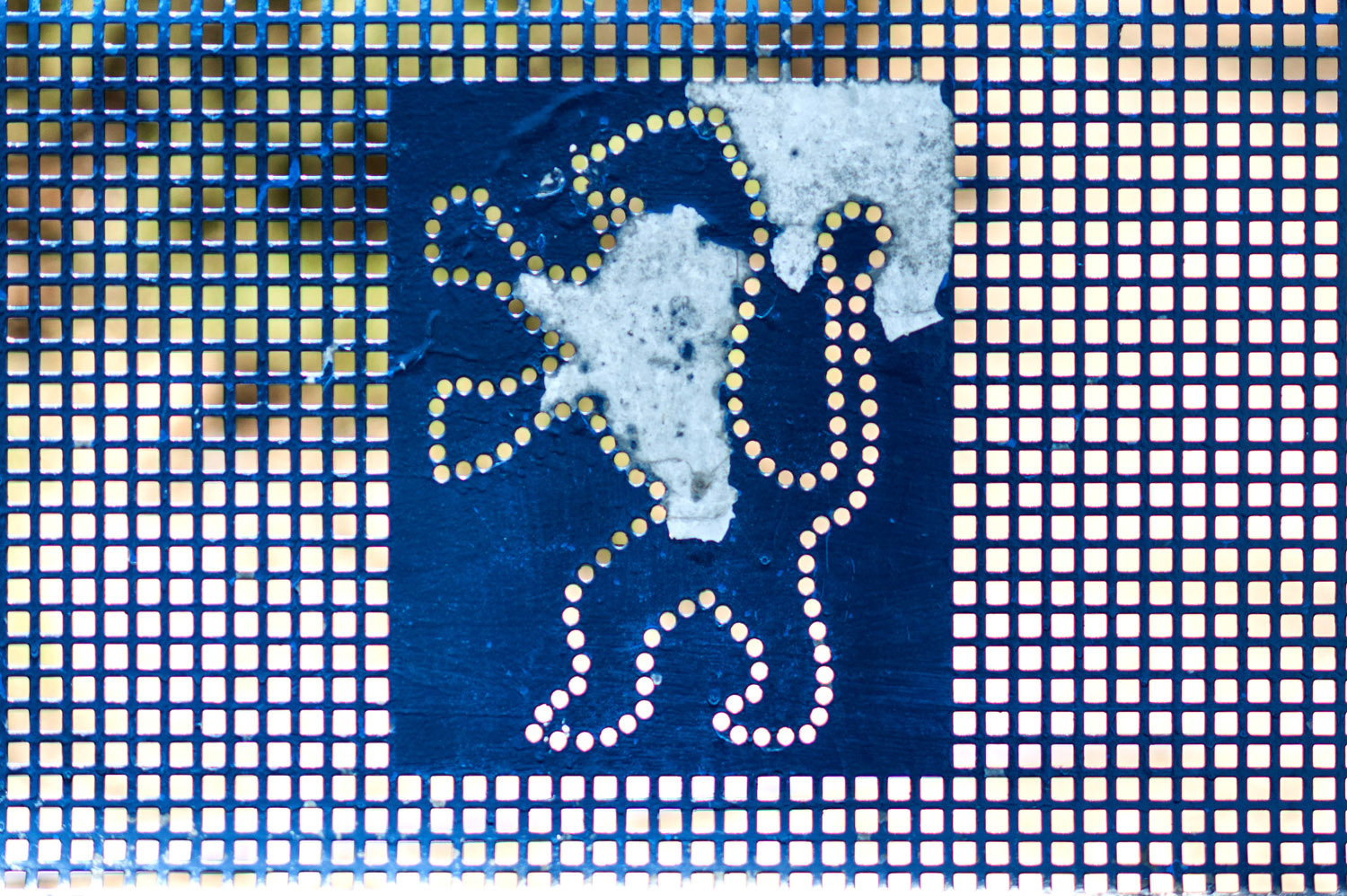

Jerusalem was the capital of the Kingdom of Judah and home to the tribe of Judah, who is blessed by his father Jacob in the book of Genesis as a “gur aryeh,” a young lion. Manhole covers, metallic park benches, and the neon-orange vests of city workers all feature the lion emblem.

A more playful version of the standing lion – seen riding a bicycle with a windblown mane and tail – adorns the many new bike-parking racks around Jerusalem.

The lion’s share (pun intended) of Jerusalem’s other lions features an eclectic remnant of the lion sculpture project launched in 2002, during which 80 lions were colorfully stylized by Israeli artists, scattered in scenic locales around the city and then sold in a public auction, with proceeds going to charity.

A decade and a half later, many of these lions are worse for the wear but remain in public view in the city center, the City Hall complex, the Jewish Quarter of the Old City and the picturesque neighborhood of Yemin Moshe, as well as on the light-rail platform in the northeast neighborhood of Pisgat Ze’ev.

Unlike the standing Lion of Judah, a large, winged lion carved from stone sits atop the roof of the Assicurazioni Generali building, an historic Jaffa Road landmark. Created by Jerusalem artist David Ozhernesky, the sculpture represents the Lion of St. Mark, patron saint of Venice and the adopted symbol of the Generali Insurance Company, whose Jerusalem branch was housed in the building from 1935-1946.

The lion is leaning on an open book inscribed in Latin with the words “Pax Tibi Marce Evangelista Meus” (Peace unto you, Mark, my Evangelist.)

A bit further east from Jaffa Road is the Lions’ Gate, built in the 16th century by the Ottoman Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. According to legend, Suleiman dreamed that he would be devoured by lions as punishment for the state of the holy city under his reign. He ordered the ruined walls to be rebuilt.

Multiple lion embossments embellish either side of the walls and give this gate its name, though there is some debate whether they are actually lions or cheetahs, a close relative to the king of the jungle.

In 1989, the West German government commissioned German artist Gernot Rumpf to design a fountain as a gift to the city of Jerusalem. His creative efforts yielded the Lions Fountain in Bloomfield Park, near the windmill of Yemin Moshe.

Rumpf’s design features a large central tree with three branches — representing the three major religions of Jerusalem — which entwine to create a “tree of life.” The tree is surrounded by bronze lions, with mice and doves at the feet of the burly beasts, depicting the longing for an ideal world of peace and coexistence.

True to the artist’s vision, the fountain has become a meeting place for a wide cross-section of residents and visitors to Jerusalem, among them Arabs and Jews who find refreshment in the cool, flowing water and take in the sweeping views of the Old City ramparts, Mount Zion and the Tower of David.

Elsewhere around Jerusalem, lions appear in murals at the Machane Yehuda market, atop a bridge connecting Kibbutz Ramat Rachel with Arnona and as sentries in gardens and doorways.

If sculpted or engraved renderings don’t appeal to you, the Jerusalem Biblical Zoo is home to more lifelike versions of big cats.