Ice cream may not always be headline news in other countries but occasionally it is in Israel. The latest news is that Froneri, the second largest ice cream manufacturer in Europe, will acquire Noga Ice Creams, part of the Nestlé-owned business Osem Group.

The deal, estimated at tens of millions of euros, marks Froneri’s maiden entry into the Israeli market and brings all of Nestlé’s Europe, Middle East & North Africa ice cream businesses into Froneri.

Multinational acquisitions seem a far cry from the modest beginnings of Israel’s commercial ice cream market, which today boasts international brands like Ben & Jerry’s, Häagen-Dazs, Mars, Motta,Magnum, Cornetto and others.

In fact, commercial ice cream was a staple in Israel even before the establishment of the state in 1948.

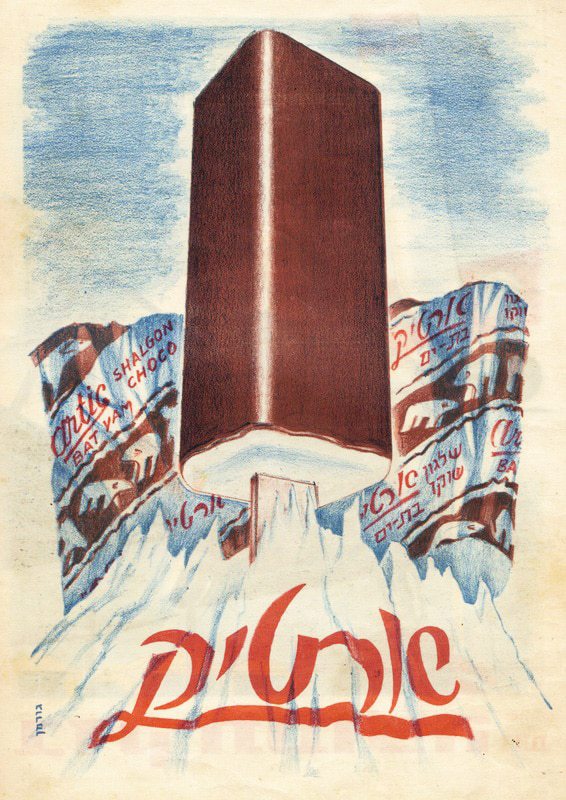

The innovation of ice cream on a stick was brought to Israel by the Artik

company, which in 1951 established a factory in Bat Yam after purchasing the rights, equipment and know-how of Belgian brand “Artic.” Having received heavy government backing and import allowances, Artik began operations in 1952.

According to a firsthand account given to the National Library of Israel,”The first ice cream… was a soft white ice cream block on a stick, vanilla flavored and about 3x3x8 cm. The ice cream was coated with a thin layer of chocolate that cracked and melted when chewed. The aluminum foil wrapper had diagonal silver and blue stripes, and on each line a series of white bears and the words‘Artic.’ This delicacy cost 15 grush which was a lot of moneyback then.”

Competition arose only a year later, in 1953, with the establishment of the Kartiv companyin Petah Tikva.

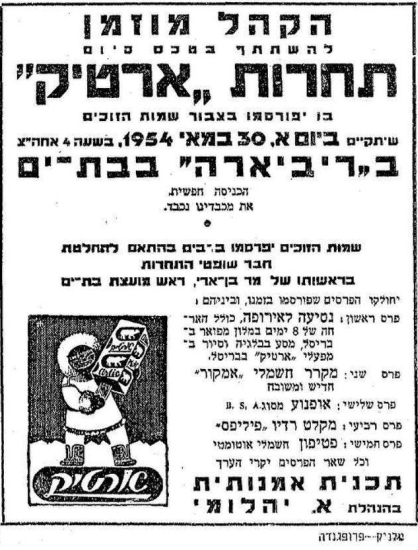

Artik launched a series of contests to promote its products against the competition. One had contestants mail in answers to the not-so-subtle question, “Why do we like one ice cream brand more than the other?” and “How can we tell the difference between ice cream brands?”

An Artik-sponsored raffle required collecting popsicle sticks imprinted with a letter; when complete, the full set of sticks would spell out the word “Artik.” The game was shut down by police, who confiscated the sticks, claiming this was an illegal lottery. In response, Artik suggested that the raid had been instigated by Kartiv. The end result was a merger of the two competitors in 1954.

In 1954, in the midst of the Tzena (austerity) period, the newly united Artik-Kartiv announced it would be raising its prices; following government objections, this was quickly followed by an announcement that it would keep prices as is.

“Artik-Kartiv” became a standard sales pitch for vendors across the young country’s beaches and movie-houses. Soon afterwards, a third Artik-Kartiv product, a round ice-cream sandwich called “Casata,”joined the rollicking rallying cry that now went, “artik kartiv shokolad banana casata casata casata!”

Today, all three of these brand names have become generic terms: artik refers to any milk-based ice cream on a stick, water-based fruit-flavored popsicles are kartivim(sometimes called eskimo, as in the Israeli cult movie Eskimo Limon), and casatot refer to ice-cream sandwiches. Israelis seldom use the official term devised by the Academy of the Hebrew Language: shalgon.

In 1956, Artik-Kartivwas granted import licenses after promising not to engage in anti-competitive activity but in reality, by the end of the 1950s, the companyheld 80-90% of the shalgon market in Israel.

In the early 1960s, however, other ice-cream manufacturers began to emerge: Whitman and Feldman both started out as popular Tel Aviv cafés (the Feldman family owned the Kapulsky chain) that branched out into ice-cream production.

At that same time, Artik-Kartiv’s management was under investigation for tax evasion and in 1963, senior managers were convicted of what was then the largest tax fraud ever uncovered in Israel.

The Strauss company had an ice-cream business as well. According to Strauss family lore, the Nahariya-based dairy entered the sector quite by accident when, in 1945, Hilda Strauss arrived in Tel-Aviv to collect money from a distributor.

“The distributor did not have cash but Hilda noticed that in the corner of the store stood an ice cream maker. She agreed to receive the machine instead of cash.” In 1962, with a new factory in Acre, Strauss was ready to take on the competition, chiefly Whitman and Artik-Kartiv.

In 1964, another competitor entered the fray. Adnir was founded by the Moshavim Movement, which licensed the most up-to-date Danish ice-cream manufacturing technology. The young and ambitious Michael Strauss was invited to manage the company.

Artik-Kartiv’s downfallwas described by Michael Strauss, who in time became chairman and president of the Strauss Group, in the book Strauss: The Story of Family and Industry by Sarit Yishai Levi.

“In contrast to Artik’s outdated and botched management, our management was creative and aggressive. Artik was not developing. They thought their success would continue automatically. While we at Adnir were constantly aware of market sentiment and the changes taking place, Artik relied on aggressiveness.

“They did not know who they were dealing with. Adnir was a strong company with economic backing and lots of money. We launched aggressive marketing campaigns with large prizes, promotions that were not considered acceptable until then. Artik was in a difficult situation. The more Adnir sold, the less they sold. In the end, Artik was sold to an English company and tried unsuccessfully to pick itself up.

“The disappearance of Artik from the landscape was one of my greatest victories.”

Something else disappeared in the 1970s and 1980s: cream. Most products sold in Israel as “ice cream” were, in fact, based on vegetable fat and not milk fat.

In an extensive 2013 Yediot Ahronot review of the sector, experts cited several possible reasons: consumer preferences for kosher non-dairy desserts, cheaper prices, and – most plausibly – a hike in the cost to manufacturers of milk fat, cream being a non-price-controlled commodity whose distribution was controlled almost exclusively by dairy monopoly Tnuva.

The exception was Snowcrest, which entered the market in the 1970s with a dairy ice cream that was distributed via ice-cream trucks exclusively. This strategy proved so successful that in 1980, Tnuva made the decision to acquire Snowcrest. Adnir was acquired by Tene-Noga in 1964, and Tene-Nogawassold to Tnuva in 1981.

In 1996, the whole of Tnuva’s ice cream business was acquired by Osem, which one year earlier had joined forces with multinational Nestlé.

Strauss continued its campaign, buying competitor Whitman in 1979. In 1991, Strauss began consolidating its ice-cream businesses and in 1996, the merger of the two brands was completed as part of the acquisition of Strauss Ice Cream by multinational corporation Unilever.

The mid-1990s ushered in a new era for Israeli ice-cream lovers, who today rank among the world’s top ice-cream-per-capita consumers.

In 2003, monolithic Tnuva underwent restructuring and in 2015, control of Tnuva was sold to Bright Food Group, the second largest food group in China.

As for Artik-Kartiv, the company went into receivership in 1971 and shut down operations in 1972. However, the brand name still exists and is still to be found on Israeli supermarket shelves, while the terms “artik” “kartiv” and “casata” are forever enshrined in Israeli popular culture.

![Elections 1977 – Likud posters] In 1977, Menahem Begin led an election upset as Israel’s first non-Labor prime minister. Credit: GPO Elections 1977 – Likud posters] In 1977, Menahem Begin led an election upset as Israel’s first non-Labor prime minister. Credit: GPO](https://static.israel21c.org/www/uploads/2019/09/Elections_1977___Likud_posters_-_GPO-768x432.jpg)