Call it what you will – Be’er Sheva, Beersheva, Beersheba, Birüsseb, or Bir Seb’a – it is the “Capital of the Negev.”

Beersheva is the largest city in the Negev desert, the center of the fourth most populous metropolitan area in Israel and the eighth most populous Israeli city, boasting a world-class university, hospital and cyber research center of international repute.

Yet it is still off the beaten track for most visitors who may not be aware of this modern city with ancient roots.

A new exhibition, “Once Upon A Time in Beersheba,” at the Negev Museum of Art presents the public with a selection of rare photographs, posters, documents and films describing life in Israeli Beersheva in its first decades, with a special focus on immigrant absorption in the 1950s and ’60s.

But the exhibition’s location is as fascinating as the images themselves.

While the Israeli city was founded a scant 70 years ago, Beersheva’s heritage is ancient. It is referred to in the Hebrew Bible numerous times as a strategic location. Archeological evidence from Tel Be’er Sheva, a dig site east of the modern-day city, indicates that the region has been inhabited since 4000 BCE.

The heart of today’s Beersheva was established in 1900 by the Ottoman Turks as a regional administrative, commercial and military outpost — again, due to its strategic location.

The building that today houses the Negev Museum was erected in 1906 as the Ottoman Governor’s Mansion, called Khonak in Arabic. Because this was a planned city – the only one of its kind under the Ottoman Empire – the building was one of a group of government edifices positioned on the main road leading from Gaza to the center of town.

During the First World War, the city was captured by the British-led Australian Light Horse brigade and the mansion became the British Army Officers’ residence.

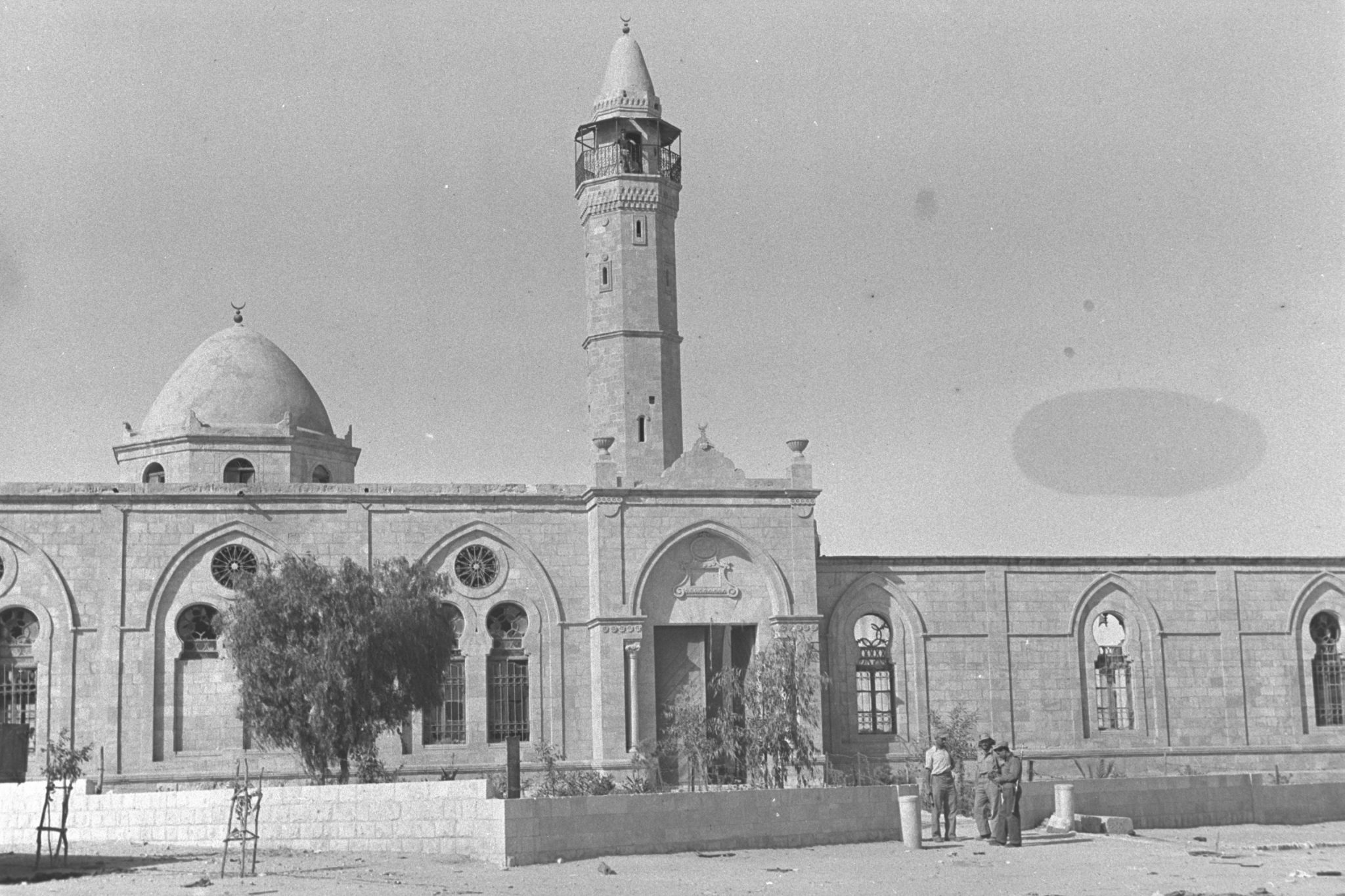

The government complex included the central administration, called the Saraya, and the Great Mosque, which was built diagonally to the course of the street to comply with the direction of prayer toward Mecca. The Great Mosque served the inhabitants of the Ottoman city: Arabs whose families came from Hebron and Gaza.

Under the British Mandate (1917-1948), Muslims formed the majority in the city and the Great Mosque continued to serve as a religious center for people from across the region.

In 1947, the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) proposed that Beersheva be included within the proposed Jewish state in their partition plan for Palestine: “The proposed Jewish State will include Eastern Galilee, the Esdraelon plain, most of the coastal plain, and the whole of the Beersheba subdistrict, which includes the Negeb.”

However, the plan was revised by the UN’s Ad Hoc Committee, which assigned Beersheva to the proposed Arab state in light of the town’s majority Muslim population.

Following the declaration of Israel’s independence, the Egyptian army stationed forces in Beersheva. In October 1948, Beersheva was conquered by the Palmach’s Negev Brigade.

Briefly used a school for Bedouin children, the Governor’s Mansion then became military headquarters for what became the Israel Defense Forces (IDF).

The neighboring Saraya building served as a detention center and the local court.

In 1950, the modern city of Beersheva was founded, and the Governor’s Mansion became its first City Hall. In 1972, the municipal administration moved to its current home, and the Governor’s Mansion became the art wing of the Negev Museum. In 1998, the structure underwent restoration. The newly refurbished Negev Art Museum was re-opened in 2004.

Far more controversial was the fate of the Great Mosque, which in 1952 had been converted into a museum of Negev archaeology and ethnography. This structure, too, fell into disrepair. The archaeological collection was removed for storage by the Israel Antiquities Authority in 1992 and restoration got underway only in 2008.

According to the museum website, “At the end of the process [in 2010], the municipality requested to resume use of the Great Mosque as an archaeological museum. However, the Association for Assistance and Protection of Bedouin Rights, the Muslim committee of the Negev, and other bodies requested that the building return to its original use as a mosque, and a public debate ensued. During the dispute, activists petitioned the Supreme Court, which in 2011 held that the building should serve as a museum ‘dedicated uniquely to the culture of Islam and the peoples of the Near East.’”

In December 2014, the Museum of Islamic and Near Eastern Cultures opened to the public. As for the Saraya, today it houses the Beersheva Police Station and the IDF Southern Command.

“Once Upon A Time in Beersheba” at the Negev Museum of Art — the one-time Governor’s Mansion – features photographs and ephemera from the Central Zionist Archives and films from the Spielberg Jewish Film Archive.

The exhibition runs through August 31 and includes meetings, walking tours and talks about the Negev and Beersheva. For more information, click here.

![Elections 1977 – Likud posters] In 1977, Menahem Begin led an election upset as Israel’s first non-Labor prime minister. Credit: GPO Elections 1977 – Likud posters] In 1977, Menahem Begin led an election upset as Israel’s first non-Labor prime minister. Credit: GPO](https://static.israel21c.org/www/uploads/2019/09/Elections_1977___Likud_posters_-_GPO-768x432.jpg)