Walking through Machane Yehuda Market in Jerusalem with Tali Friedman, head of its merchant’s association, is a slow progression. Vendors want to say shalom, register a complaint, give her a hug.

“What a good heart you have!” exclaims Aliza, the grandmotherly owner of one of the myriad fresh produce stalls, as Friedman embraces her.

The market just kicked off its centennial year with concerts, a chef competition, art installations and the inauguration of the International Markets Association attended by market heads from Florence, Barcelona, London, Berlin, Kyoto, Mexico City and Tbilisi (see box).

Friedman, a 47-year-old chef and mother of four, plans more cultural events to celebrate 100 years of this place she calls “a museum of life, where you meet all of Israeli society.”

Machane Yehuda is her second home. Its vendors and patrons are like family.

But she’s facing a challenge: How to retain the market’s warm, old-timey vibe even though it’s become a wildly popular culinary and nighttime club-and-pub scene.

In fact, Machane (pronounced “makh-a-neh”) Yehuda is now one of the top tourist spots in Israel.

Its narrow lanes are crowded with shoppers, diners and tourists taking tastes and shooting selfies amid the tantalizing mounds of produce, spices, ethnic foods, bakery items, meat, fish, halvah and so much more.

“The new life of the market is also beautiful. We just need to find a balance. We are over capacity and don’t know how to handle it,” Friedman says while grabbing a noontime sandwich and java at the jam-packed Roasters coffee shop.

“It’s a beautiful place and we want to preserve it first as a market, where you see the old lady with her cart buying her fruits and vegetables and cilantro and parsley, and you can almost smell what she’s cooking.”

100 years ago

Hard as it is to imagine, the lively market was once a barren lot at the edge of a Jerusalem neighborhood named Machane Yehuda (Camp of Yehuda) in memory of the brother of one of its founders.

In the early 20th century, local Arab farmers began selling their produce in the lot and cobbled together some stalls and storage sheds as a makeshift shuk (Arabic for market).

The Etz Chaim Yeshiva next to the market built a row of shops and rented them to merchants. Today, the abandoned yeshiva building is being refashioned into a hotel.

A 40-meter centennial mural was just unveiled on the wall between the properties, marking the 1922 official British recognition the market, which then had about 40 vendors.

Friedman laughs when I ask how many vendors are now in the shuk. She tells me that it houses about 620 businesses, but the total number of Jews and Arabs earning their livelihood here is “a thousand, maybe double that. We’ve never counted.”

In September 2020, despite the pandemic, 82% of the multiethnic mix of merchants came out to elect a new leader. Friedman won 86% of the votes.

Culinary hotspot

She had big shoes to fill. Her predecessor, the late Eli Mizrahi, himself the son of a Machane Yehuda merchant, began transforming Machane Yehuda into a hotspot in 2002 with the opening of Café Mizrahi.

This was a bold move, considering that the market was reeling in the wake of deadly terrorist bombings in 2000 and 2002.

But as Mizrahi told ISRAEL21c 12 years ago, the market’s woes were as much the product of municipal neglect as Arab terror.

He got the leverage he needed when city officials sought his cooperation in planning Jerusalem’s light rail, which eventually opened in 2011 and runs past the shuk. Mizrahi told them that the merchants association “would only cooperate if they renewed the market.”

The cleanups and fixups encouraged new businesses to enter the shuk, bringing in younger crowds for food and drink, even after hours.

Friedman says, “When Eli Mizrahi opened his first coffee shop here, he started a new life in the market. Highly regarded chefs, who already were shopping here, now had a place to sit and talk. And the culinary aspect of the market took off.”

This led to ventures such as the Machneyuda Group, which flourished into a global enterprise under chefs Assaf Granit and Uri Navon and partners.

Friedman pioneered culinary tours of Machane Yehuda 18 years ago and established her atelier in the market about 14 years ago. The cooking classes are now mostly led by her brother, Yosef Hillel.

A family affair

Machane Yehuda is a family affair. Friedman says most of the businesses are run by the third or fourth generation of original owners, including the extended Mizrahi family.

Friedman notes with pride that these vendors have always adapted to changing customer needs and expectations.

The renowned Basher Fromagerie began in the shuk in 1956 as a modest reseller of soon-to-expire dairy products at rock-bottom prices. Large, impoverished ultra-Orthodox families from nearby Meah She’arim came daily to purchase these bargains, Friedman recalls.

The original shop, expanded and owned by the third generation of the Basher family, now stocks hundreds of Israeli and European cheeses, fine wines and other imported delicacies. Branches were established across Israel.

Does this mean the local gentry no longer shop at Basher? Not at all, says Friedman. “The grandma with the cart will not buy the [French] Gruyere but she can buy the [Israeli] Hameiri.”

This gets back to Friedman’s insistence that Machane Yehuda remain true to its essence.

“For my business to exist, I need the market to stay an authentic market. The chef restaurants here are built on the produce in the market. The bars and nightlife are also beautiful but we have enough of them and I don’t want to see more,” she says.

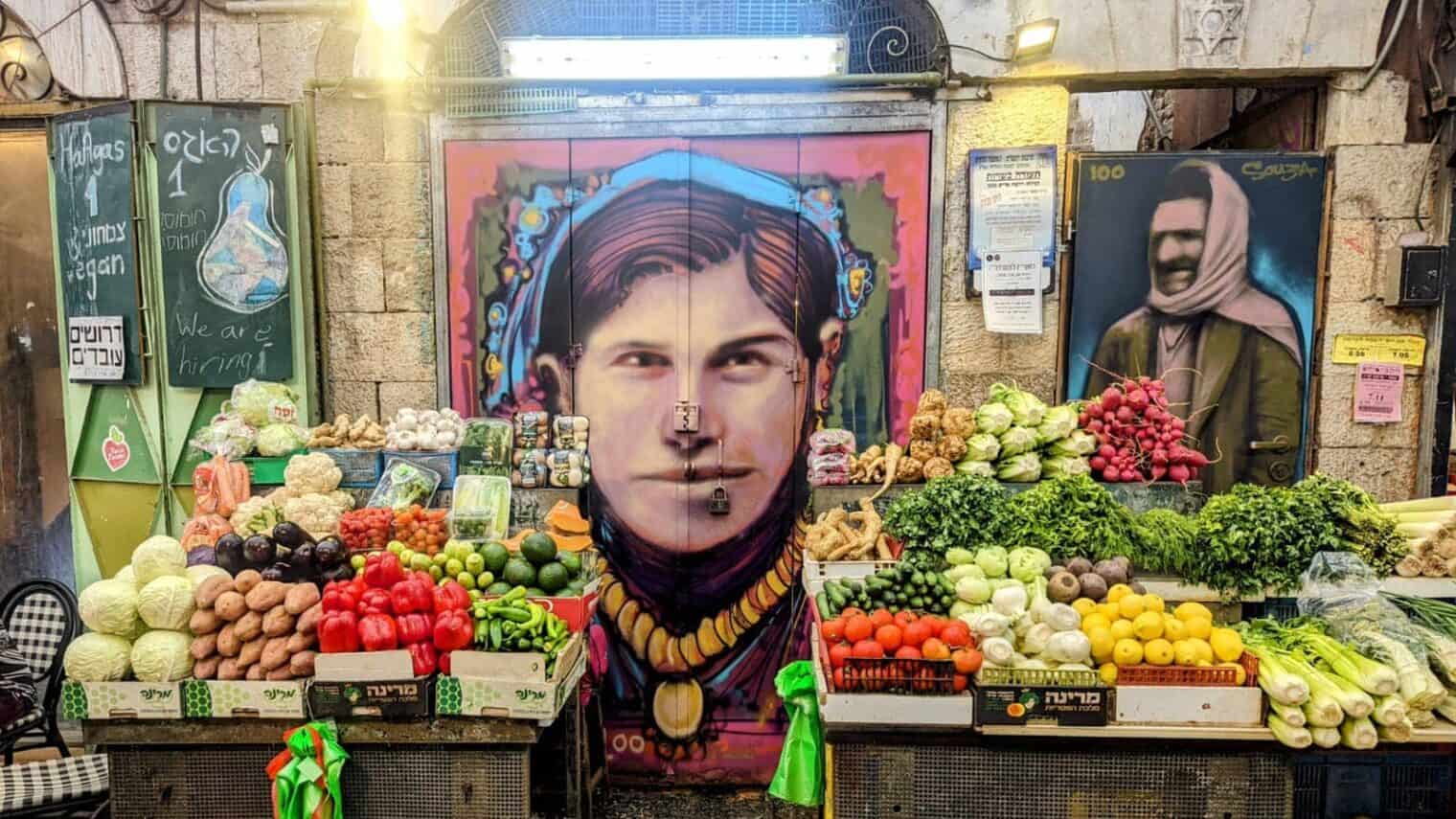

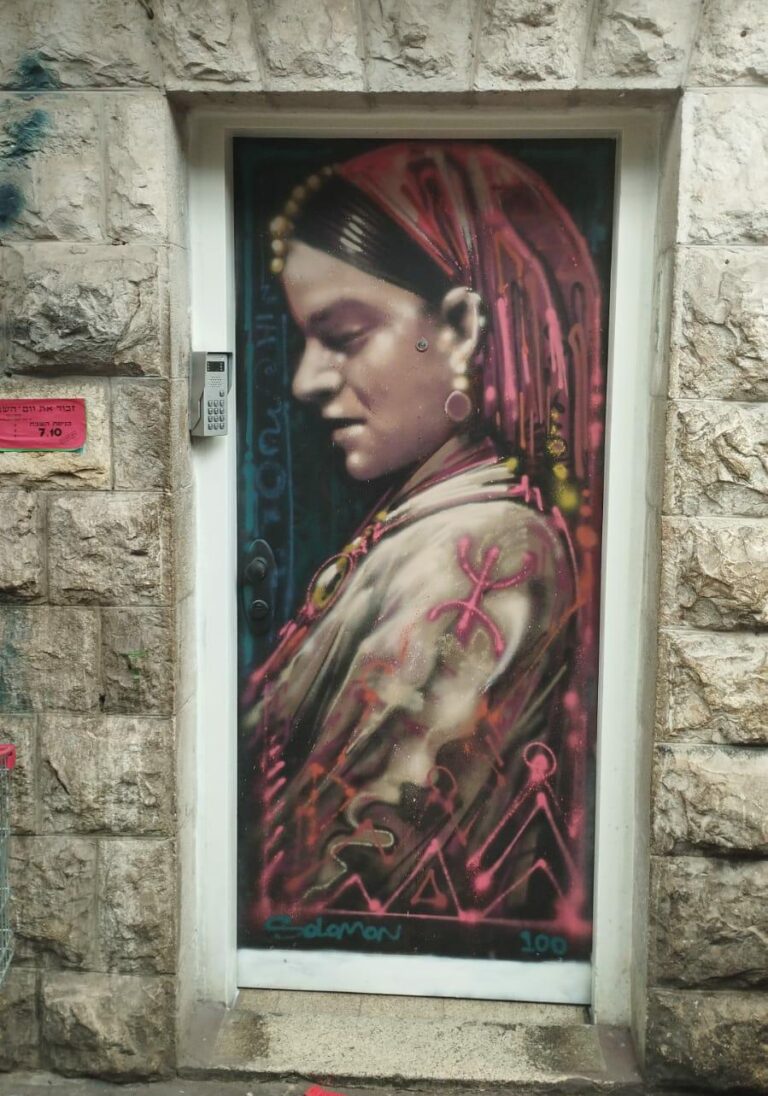

Street art in the shuk

Underlining her respect and gratitude to the original vendors and creators of the market, Friedman hired street artist Solomon Souza to paint 250 portraits of Machane Yehuda notables on the walls and doors of the market.

Souza won worldwide recognition for spray-painting fanciful animals, biblical scenes and portraits of pioneering personalities of the past on 60 shutters of the shuk’s stalls in 2015.

Also planned are new exhibitions, including a rehanging of Israeli art photographer Eyal Granit’s exhibition of vegetable still-lifes first installed at the market in 2020.

“I always want to combine art and culture with the people,” says Friedman. “We have many talented artists in Jerusalem and if we can get more budget I want to give it to them.”

She’s also seeking a budget for a new roof and flooring for the closed part of the shuk, as well as more bathrooms to accommodate the ever-increasing visitors. In the past four years she has implemented improvements such as daily cleaning (done at 3 in the morning before delivery trucks start arriving at 4).

Machane Yehuda, says Friedman, is “the main anchor of the city and for all of Israel.”