For the millions of Israelis who took shelter against Iran’s massive attack on April 14, it’s probably incomprehensible that once upon a time, El Al ran a daily flight from Tel Aviv to Tehran. But that used to be the case, before ties between Iran and Israel took a sour turn.

To make sense of these tumultuous relations, ISRAEL21c spoke with Prof. David Menashri, professor emeritus at Tel Aviv University and a leading Israeli scholar on Iran.

Born in Tehran, Menashri immigrated to Israel at the age of five. In the 1970s, he spent two years at Tehran University doing research and has since published extensively on Iranian education, politics and foreign policy.

“After Israel was established [in 1948], we made ties with what we called the periphery countries – Turkey, Iran and Ethiopia – which are the neighbors of our neighbors, or the enemies of our enemies,” he explains.

Iran, while a Muslim country, isn’t Sunni (like Saudi Arabia, for example) but Shi’ite. Neither is it Arab, making it a perfect fit for this goal.

In the 1950s, Menashri points out, newborn Israel needed “all sorts of things that we could get from Iran, like oil.”

By the 1960s and 1970s, Iran had undergone a process of modernization, secularization and Westernization. Israel became attractive to Iran, among other things, because of the influence the Shah of Iran believed the Jews had in Washington.

In what possibly constituted one of the weirdest nights in the country’s history, Israel faced a massive UAV and missile attack launched by Iran on the night of April 13.

With millions of people awake in the middle of the night, watching the skies or their TVs, it was a historic event that was thankfully thwarted in a most magnificent manner.

“Iran saw in Israel an ally in order to improve its relations with the United States, but especially an ally in its battle against the Arabs, that were also Iran’s enemies,” Menashri explains. “Israel’s very existence and its continued war with the Arab world also took a load off Iran. Iraq, for example, was busy with Israel instead of with Iran.”

In those two decades, Iran-Israel relations were warm yet unofficial. There were daily El Al flights from Tel Aviv to Tehran. An Israeli school in Tehran catered to the children of Israeli families who made the Iranian capital their home while on business.

Turning point

The relationship began turning colder with the Islamic Revolution from 1978 to 1979.

“For the first decade after the revolution, there was war between Iran and Iraq, from 1980 to 1988, and Iran was busy with that. It even held negotiations with Israel and bought American weapons though Israel. Iranian leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini said that when you’re drowning, you’re allowed to hold on even to the tail of a snake to survive,” says Menashri.

The first Gulf War in the 1990s, Menashri notes, saw the US dismantle the strength of Iraq, Iran’s main nemesis in the region, enabling Tehran to turn into a regional power.

In 2002, the US invaded Afghanistan, and a year later toppled Iraq’s Saddam Hussein. Again, Iran became a leading power in the region.

“After the revolution, everything that was in the days of the Shah was considered bad, and everyone who was considered well in Iran was now viewed negatively,” Menashri says.

“Israel and the US were friends beforehand, and therefore not good any longer.”

An outsider

“After the revolution, the view was that Israel is an outsider in the Middle East, that it doesn’t have the right to exist, and certainly not the right to exist in Palestine, on the lands of the Palestinians, and certainly not with Jerusalem as its capital,” says Menashri.

“This is then mixed in with politics. If you want to become the leader of the Muslim world, you must wave the Palestinian flag, even if only in a tactical manner. For Iran, which is Shi’ite and not Sunni, the raising of the Palestinian flag and becoming the vanguard of the struggle against Israel provides it with legitimacy in the Muslim world in which it wishes to be dominant.”

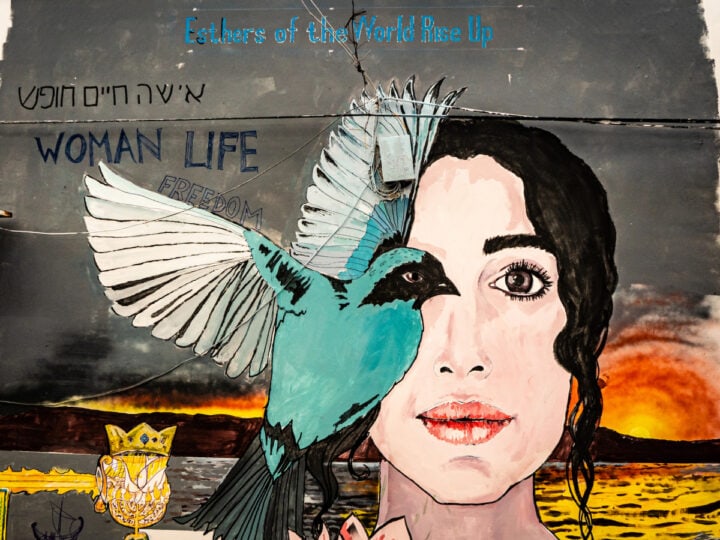

These views, Menashri stresses, are not necessarily shared by the general public, which often resents Iranian involvement and subsequent loss of life abroad, and also criticizes the regime for its actions at home. An example is the 2022 demonstrations against Iran’s treatment of women.

To maintain itself, Menashri explains, the Iranian regime established several guards, including the Revolutionary Guards that spawned the Quds Force led by Qasem Soleimani. Soleimani, Menashri says, built the proxy network that is now servicing Iran against Israel, from the Houthis in Yemen and the Shi’ite militias in Iraq to Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in Gaza.

Before dawn on April 14, the Islamic Republic of Iran launched approximately 170 attack drones, 130 cruise missiles and 120 ballistic missiles at Israel.

The Israel Defense Forces intercepted 99 percent of them with help from the military forces of the United States, Britain, Jordan and France. A few ballistic missiles got through, causing minor damage at Nevatim Airbase in southern Israel. The only Israeli casualty was an Arab Bedouin girl wounded by shrapnel.

“These proxies are meant to come to the aid of Iran and not for Iran to come to their aid. That’s why, a day after October 7, the Iranians said that since they weren’t notified of the upcoming attack, Iran isn’t committed to it and won’t take part in it,” he says.

“In the meantime, its proxies have taken part in it. The Yemenites are busy in the Persian Gulf, the Iraqi militias are shooting toward Israel and so is Hezbollah, but none of them are really taking a part in the war,” he adds.

“For Iran, it was convenient that its proxies were doing what they were doing – it took a load off them, spared them casualties and allowed them deniability.”

All this changed, of course, on the night of the Iranian attack in April.

“On that Saturday night, Iran launched UAVs and missiles at Israel. Even before they reached Israel’s borders, Iran was busy celebrating its victory, the fact that they managed to scuttle Israelis into shelters,” Menashri notes.

“They announced that for them the fighting was over, and that if Israel will attack, they’ll retaliate with greater force. They didn’t wait to see what would happen. They thought that it was within the lines of what’s permitted.”

Israel then had a dilemma about how to respond “in a way that wouldn’t demand an Iranian response, not to mention opening a direct front against Iran. Israel doesn’t have a clear interest to do that – when it’s stuck in Gaza, entangled in Lebanon, dealing with Iraq, Syria and Yemen,” says Menashri.

War would mean US, Russian and Chinese involvement

“To open a front against Iran would mean the United States entering the situation, and perhaps following that also active Russian involvement and some Chinese involvement,” he says.

“As for the Israeli response, we only know what we know. It’s unclear what the scope of the activity was, and Israel didn’t take responsibility for it, and neither did Iran blame Israel or say there’d be a response to the Israeli action. This is despite the Israeli retaliation hurting them – it hit things accurately and got past their defense systems, which perhaps the Iranians didn’t think was possible.”

This, Menashri believes, is because Iran doesn’t want a full-fledged war with Israel, which would be challenging and further expose Iran’s proxies to an Israel threat. Furthermore, Iran would have to rely on Russian and Chinese support in the face of confrontation with the United States, all while trying to promote its nuclear program.

“Iran is claiming restraint; Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei calls it ‘strategic restraint.’ That’s why I think that Israel, for lack of choice, should also show some restraint.

“Can we release the hostages, go into Rafah, return our citizens to their homes on the Gaza border and northern border, open up a front against Lebanon and continue to fight Iran’s proxies, and add to that a direct confrontation with Iran? Any reasonable person will tell you there’s no way to do it.”

Strategic opportunity

The Iranian attack, Menashri says, has created a strategic opportunity never seen in the Middle East: a potential US-led axis of Israel, Saudi Arabia and other moderate Muslim countries such as Jordan, Egypt and the Emirates.

“The Iranian threat is just as threatening to them as it is to us, and that’s why in more regular times we should have snatched up this opportunity to join this axis, that could calm down the region and lead to Israeli-Saudi relations, followed by relations with other Muslim countries. The problem here is that for this, you’d need to pay in Palestinian coin – that is, pay some lip service or do a gesture regarding the Palestinians.”

Menashri thinks this would prove difficult, yet Israel should not leave itself outside of the new order being created in the Middle East. The US and Saudi Arabia, he notes, are warming their relations whether or not Israel will join this move.

“The US is going to allow Saudi Arabia to attain nuclear energy and military capabilities. It’s better for us that we’ll be a part of this equation than outside of it,” he concludes.