The war raging between Israel and Hamas, following Hamas’ October 7 massacres and kidnappings in Israeli Gaza border communities, has brought the Gaza Strip to headlines around the world.

But though many people are seeing images of the conflict on their TVs or phones, very few know about the complicated and tumultuous history of this tiny area. Why is this region in conflict, what are the issues, and how did we get here?

ISRAEL21c spoke to two Israeli experts to help bring a bit of clarity.

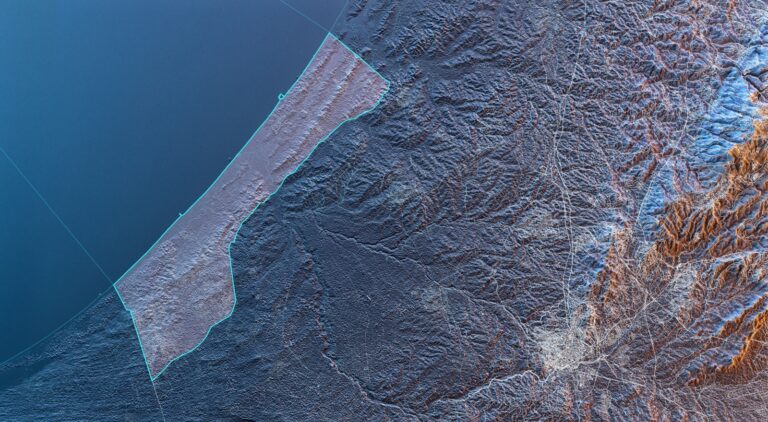

“The ‘Gaza Strip’ is a term that developed only in 1947. There was the city of Gaza, surrounded by other nearby cities and villages, and these were all part of a larger space,” explains Prof. Gideon Biger, a professor emeritus of historical and political geography at Tel Aviv University.

For hundreds of years culminating in World War I, the entire region was part of the Ottoman Empire, and in the last years of the empire it belonged to a special administrative district called Al-Quds, the Arabic name for Jerusalem, he says.

“When discussing Gaza, we’re talking about a place that isn’t exactly periphery, but it’s also not one of the leading cities in the area, such as Jerusalem, or even, to a certain extent, like Nablus, Hebron or Jaffa,” adds Dr. Michael Milshtein, the head of the Palestinian Studies Forum at the Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies at Tel Aviv University.

A line is drawn

The first step toward the present-day Gaza Strip, Biger says, was taken at the beginning of the 20th century.

“In 1906, a line was drawn between Egypt – which was then under British de facto rule – and the rest of the Ottoman Empire. It would eventually become the border between Israel and Egypt, and its northern part delimited the present-day Gaza Strip from the southwest. This is what today we call the Philadelphi Corridor between the Gaza Strip and Egypt,” Biger says.

After WWI, the area became part of the British-ruled Mandatory Palestine.

“During the mandatory period, the British decided that the 1906 line would be the border between Egypt and Palestine, and as a result, the whole area from Rafah northward became part of the Eretz Yisrael, or Palestine. There still isn’t [at that time] a Gaza Strip,” he notes.

Milshtein describes British Mandate-period Gaza as a large city “that’s almost completely Muslim, with very few Christians. It’s not notable for economic, political or even military activity. Up until 1948, the area of what would become known as the Strip is characterized by three main types of populations.

“The first is the urban population, coalesced around large families in the area. Then, there is the agricultural population, though there are very few agricultural communities. Beit Lahia and Beit Hanoun, which we now hear about on the news, were such agricultural communities. Finally, there’s the semi-nomadic Bedouin population, found especially in the center of the Strip,” he tells ISRAEL21c.

“Since there weren’t any borders at the time, Gaza’s main connections were with Beersheva, which was a completely Muslim city, and the southern Hebron Hills. There were trade ties, marriages between people from these locations and Bedouin nomads crossing them,” he says.

Partition suggested, rejected

Things changed when the British decided to return to the United Nations the mandate that it received to rule the area. This happened on May 14, 1948.

In response, the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) recommended to partition the area into a Jewish state and an Arab state. The area from Rafah to Ashdod, now in Israel, would be part of the Arab state.

UNSCOP recommended that the Arab state would go three to four miles inward from sea, giving shape to an area associated with what we know as the Gaza Strip.

But the Arab neighbors of the newly established state of Israel rejected that two-state plan and declared war, which formally ended with the 1949 Armistice Agreements.

“At the time of the agreements, the area of Gaza was under Egyptian military control, and remained so. This, in fact, created the term that we use to this day – the Gaza Strip. It was officially created in the armistice agreements in February 1949,” Biger notes.

Some small land swaps between Israel and Egypt further shaped the Gaza Strip of today. Egypt never annexed the Strip; instead, it was an occupied military area.

Synonymous with hardship

“The big story after the 1949 Armistice Agreements is what happened to the people in the Strip,” says Milshtein.

“At the end of the war, there’s nearly 300,000 people in the Strip, but almost two-thirds of them are refugees, people who didn’t live there before 1948. These are people from Jaffa and Ramla, and Bedouin from the Beersheva area,” he tells ISRAEL21c.

“Since 1948, 66 percent of the population of the Gaza Strip is not local, and a relatively small area suddenly tripled its residents. This greatly impacted the political, social and economic portrait of the Strip. Since then, the Gaza Strip is synonymous with hardship – the largest refugee camps are in the Strip – and with a constant state of unrest,” he says.

Under Egyptian control for nearly 20 years, political activity in Gaza was not allowed. After Israel defeated Egypt in the 1967 Six-Day War, Gazans were able once again to travel freely to family and friends in Israel. But Gaza also became the center of persistent political and military activity, says Milshtein.

1906: A line is drawn between Egypt, ruled de facto by Britain, and the rest of the Ottoman Empire. Its northern part delimited the present-day Gaza Strip from the southwest.

1919: The British ruling Mandatory Palestine adopt the 1906 line as the boundary separating Egypt and their mandatory territory, including the Gaza area.

“It’s not for nothing that Hamas grew in the Gaza Strip and not elsewhere. Because against the very difficult backdrop of the Gaza Strip, you get the development of radical movements, and you get the development of Hamas.”

Disengagement

Also after 1967, Israel began establishing Jewish settlements in the Gaza Strip. In 1982, when Israel returned the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt following a peace agreement signed a few years earlier, the settlements in Sinai also moved to Gaza.

“The peace with Egypt didn’t dramatically change anything, because there still wasn’t a border between Israel and Gaza,” Milshtein explains.

As part of the Oslo Accords between Israel and the Palestinian Authority in the early 1990s, Israel transferred the civil administration in the Gaza Strip to the Palestinian Authority, except for the areas of Israeli settlements.

“The story begins to change with the Oslo Accords, when for the first time a fence is erected around Gaza, and between the Jewish settlements in Gaza and the rest of the area,” says Milshtein.

In the summer of 2005, Israel forcibly removed all 8,600 Jews living in these 17 settlements. Gaza became, for the first time, an area completely Palestinian and under Palestinian control.

Border crossings

Movement between the Gaza Strip and Israel was made possible via border crossings, such as the Erez Crossing, dependent on the security situation.

“When the Palestinian attacks increased, we built a fence and carried out all these security measures that we thought would protect us – when they tried to build tunnels, we built a huge fence inside the ground,” Biger says.

Yet even after Hamas came to power in Gaza in 2007, the crossings remained open to goods and people. Humanitarian aid continues to flow through even during the war.

“Up until October 7, many Gazans worked in Israel – they came in every morning and went back in the evening. There were also goods destined for the Gaza Strip that were unloaded at Ashdod Port and transferred to the crossings. This all worked until October 7,” Biger notes.

Not a country

Aside from the crossings to Israel and Egypt, Gaza is cut off from other places.

“There’s no maritime border in the Gaza Strip because the Gaza Strip is not a state,” Biger explains.

“When we transferred autonomy there, we determined a 12-mile area in which fishermen from the Gaza Strip can fish” during times of peace. Israel patrols the coast to prevent terrorist attacks from the sea.

“The Palestinians claim that this is their sovereign area, like the territorial waters that all countries have, and they also claim an economic zone. But since they are not a country, this has no legal significance,” he says.

“There was a time when there was the idea of creating a safe passage between Gaza and Hebron, as well as establishing an airport and a seaport. There was talk about perhaps connecting the Gaza Strip and the West Bank, with a road that would pass from the northern Gaza Strip via Kiryat Gat and the Tarkoumia checkpoint so that the Palestinians could travel from Gaza to Hebron and back. None of that happened,” he adds.

Worsening problems under Hamas

When Hamas came to power in 2007, taking control of the strip from rival Palestinian faction Fatah, life in the Gaza strip began to get worse.

In the wake of its election victory, Hamas fighters took Fatah officials prisoner, and either executed them or expelled them from Gaza. At least 161 people were killed and another 700 wounded during the fighting, according to the Palestinian Centre for Human Rights.

The outcome was that the Palestinian territories were now divided into two – the West Bank governed by the Palestinian Authority, and Gaza controlled by Hamas. A division that remains today.

“Hamas has taken over the Gaza Strip and is running it as a dictatorship – one party with one politics, and brainwashing taking place in education and charity institutions,” says Milshtein.

Since 2007, Israelis harbored the hope that Hamas would “moderate and invest more in civil life, turning further away from its ideological adventures,” he says. “But unfortunately, Hamas is motivated along the lines of jihad. It’s not interested in the sewage systems of Deir al Balah or schools in Beit Hanoun. Civil and economic hardships are omnipresent. In terms of infrastructure, employment and the like, there’s ongoing and even worsening problems over the years.”

In the years since it took power, Hamas has started three wars with Israel — in 2008, 2014 and the present war– interspersed by smaller-scale conflicts and intermittent streams of rockets and incendiary devices which have rained down periodically on Israel’s southwest and center.

The Israeli response in 2008, Milshtein notes, included maneuvers inside the Strip. Had Israel wished to, it would have been able to destroy Hamas more easily back then.

Smuggling and terror tunnels

It wasn’t until 2014 that Israel became aware of the weapon-smuggling tunnels dug throughout Gaza, the majority of which reportedly remain intact today.

“The smuggling existed even before the second intifada [September 2000 to February 2005]. There were substantial tunnels between Egypt and Gaza, run by professional smugglers. Hamas smuggled whatever it needed through them, as did the Palestinian Authority,” Milshtein says.

“This all received a boost when Hamas came to power. In the first decades of the 2000s, we reached a situation where there weren’t only smuggling tunnels from Egypt to Gaza, but also tunnels that cross the border between Israel and Gaza. That’s how the kidnapping of Gilad Shalit occurred in 2006, and that’s how many attacks were carried out in the 2014 operation.”

The thousands of rockets launched from Gaza into Israel in recent months aren’t new; it’s been happening since the early 2000s.

“They began shooting Qassam rockets at Sderot, and then took things to another level when they started smuggling in pieces of Iranian Fajr rockets that can reach all the way to Tel Aviv,” Milshtein explains.

“They don’t only smuggle in whole rockets, but also the means to manufacture them – engraving mechanisms and raw materials,” Milshtein says.

“That’s how we reached this war with Hamas having an arsenal of dozens of thousands of rockets of all ranges. Their arsenal was seriously damaged, and while they still have more it’s getting harder for them to get more due to the increased Israeli control of the Philadelphi axis.”

In the past eight months, the IDF has discovered a whole underground city comprising hundreds of miles of interconnected tunnels used by Hamas to move goods and fighters, to hide in and even for its leaders to run a war from.

Biger says nobody knows the future of the Gaza Strip.

“There are all sorts of ideas. There are some who want to go and settle back there, there are others who want to return management to the residents. There are those who want international Arab management of it, and others who want to return it to the control of the Palestinian Authority,” he says.

“But at the moment, there is no decision by the government of Israel or any other body what will be done in the Gaza Strip.”