All is not well in the Mediterranean Sea as indigenous species and habitats are being decimated by foreign species crossing the Suez Canal.

The 2015 expansion of the Suez Canal, one of the world’s most important corridors of commerce, is the main reason marine life in the Mediterranean Sea has taken a dangerous downturn that could cause human health issues, said Prof. Bella Galil of the Israel National Center for Biodiversity Studies at Tel Aviv University’s Steinhardt Museum of Natural History.

“The Mediterranean Sea is the most invaded marine basin in the world,” said Galil, lead author of a study published recently in Management of Biological Invasions.

In 2015, a green glowing phosphorescent jellyfish, usually spotted in Japan, was observed for the first time in the Mediterranean Sea during a routine survey by Israeli marine scientists. Its arrival showed evidence of non-indigenous species in the Mediterranean Sea.

“The number of non-indigenous species greatly increased between 1970 and 2015. 750 multicellular non-indigenous species were recorded in the Mediterranean Sea, far more than in other European seas, because of the ever-increasing number of Red Sea species introduced through the Suez Canal,” said Galil.

This raises concerns about the increasing introductions of additional species and associated degradation and loss of native populations, habitats and ecosystem services.

In their new study, the authors present data that marine-protected areas in the eastern Mediterranean, from Turkey to Libya, have been overwhelmed by non-indigenous species and serve as veritable hot spots of bio-invasion.

A hope for effective intervention

Galil says the development and implementation of a management policy have been slow, despite a century of scientific documentation of marine bio-invasions in the Mediterranean Sea.

The Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment and the Coastal Region of the Mediterranean, part of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Regional Seas Programme, adopted an “Action Plan concerning species introductions and invasive species in the Mediterranean Sea” in 2003.

But the UNEP has “shied away from discussing, let alone managing, the influx of tropical non-indigenous biota introduced through the Suez Canal. So far no prevention and management measures have been implemented,” say Galil and her associates.

Biotic communities are already fragile due to manmade stressors such as pollution and overfishing. Non-indigenous species redistribute nutritional resources and remove important actors in the ecosystem, rendering these communities even more susceptible to extinction.

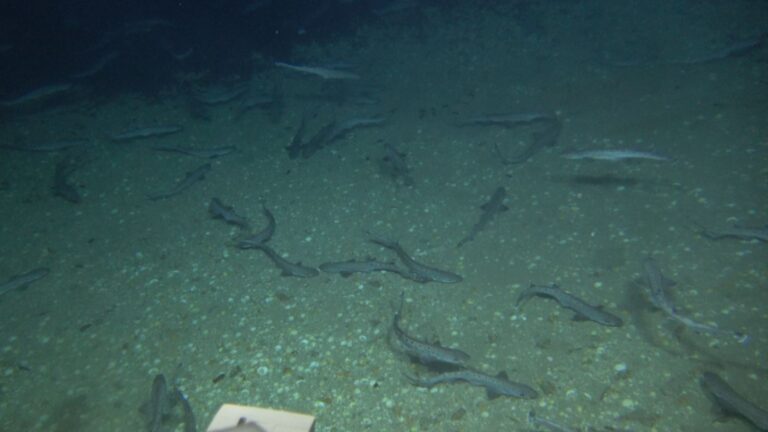

In the eastern Mediterranean, which contains the world’s oldest oceanic crust still in place at the bottom of the sea, algae-dominated rocky habitats have been decimated by large populations of herbivorous fish introduced through the Suez Canal.

The two voracious grazers, Siganus luridus and S. rivulatus, have transformed lush rocky reefs into “barrens,” dramatically reducing habitat complexity and altering the community structure and food web.

In addition, a small Red Sea mussel has replaced the native mytilid along the entire Mediterranean coast of Israel, forming dense “carpets” of nearly mono-specific species.

The authors of the study raised their concerns on effective management of non-indigenous species introductions into the Mediterranean Sea at a EuroMarine workshop in Ischia, Italy, last year.

The discussion resulted in the “Ischia Declaration” that laid down principles for an effective, science-based, transboundary management. The declaration was approved by the general assembly of EuroMarine, a network of 73 research institutions and universities, funded by the European Union.

“We hope that this new research will be used to construct a science-based effective management of marine bio-invasions and prevent, or at least minimize, the influx of additional non-indigenous species into the Mediterranean,” said Galil. “Time will tell whether these aims are achieved or legislators and management continue to put off confronting this difficult issue and pass the environmental, economic and social burden to future generations.”

The researchers are currently investigating pollution and other factors related to non-indigenous species.