“Deep-sea coral gardens that took thousands of years to grow could be gone with one swipe of a fishing net.” Hadas Gann-Perkal, SPNI

Sunlight does not reach the Palmahim Slide, a rare geological formation deep in the Mediterranean Sea about 30 kilometers (19 miles) off the coast of Tel Aviv.

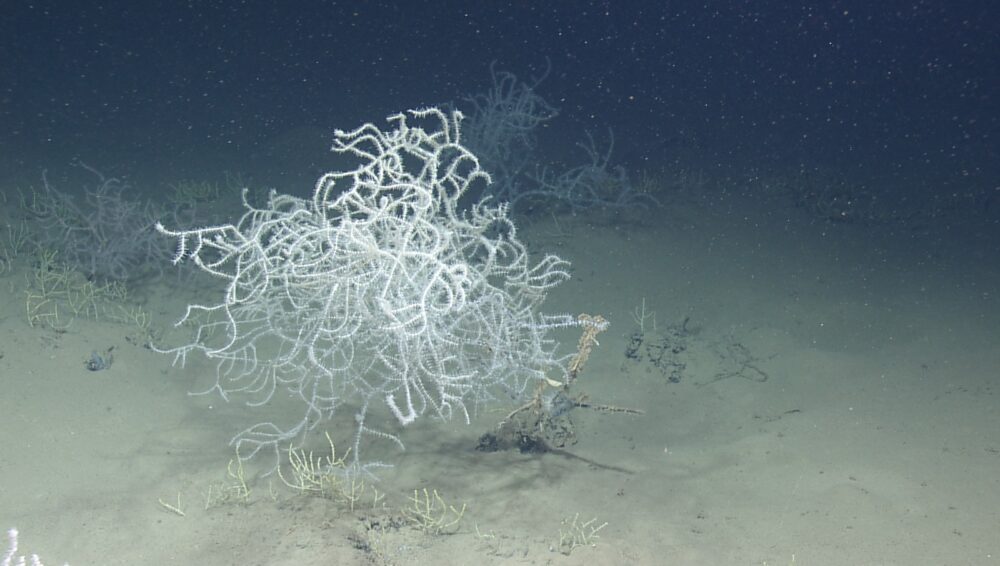

And yet unique creatures flourish in this pitch-black, 1,000-square-kilometer (386-square-mile) hilly habitat of coral gardens, methane seeps, brine pools and other underwater wonders.

Formed in antiquity by a gradual landslide onto the seabed, the Palmahim Slide is a biodiversity hotspot where blackmouth catsharks breed and bluefin tuna spawn, according to international studies led in the past decade by Yizhaq Makovsky of the University of Haifa and the Israel Oceanographic and Limnological Research.

In July, the Palmahim Slide (also called a Disturbance) became the first Israeli Hope Spot designated by Mission Blue, oceanographer Sylvia Earle’s organization dedicated to exploring and protecting significant marine areas.

“The diversity discovered there is nothing like anything seen before in the southeastern Mediterranean Sea,” said Earle, who was the first female “aquanaut” on Jacques Cousteau’s legendary ocean explorations.

Mission Blue has identified 144 Hope Spots deemed critical to the health of oceans and seas.

Earle urges Israeli policymakers to “follow in the Hope Spot’s steps in declaring 850 square kilometers of the Palmahim Slide as a no-take, give-back marine reserve large enough to protect the marine life that is there and allow no destructive activity in the reserve and its vicinity.”

Earle’s endorsement provides a spot of hope for marine projects coordinator Hadas Gann-Perkal and marine ecologist Ateret Shabtay of the marine program of the Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel (SPNI).

Together with the Israeli Nature and Parks Authority, Gann-Perkal and Shabtay have been advocating with Israeli and international authorities, such as the Italy-based General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean, to declare most of the Palmahim Slide a protected area.

“Getting international recognition for the fact that this spot should be protected has already helped in our talks with the decisionmakers responsible for the marine environment,” Gann-Perkal says.

They want to shield it from habitat-destructive oil and gas exploration and deep-sea fishing, while preserving it for scientific research that ultimately would benefit humankind.

Like exploring outer space

“Deep-sea coral gardens that took thousands of years to grow could be gone with one swipe of a fishing net,” Gann-Perkal tells ISRAEL21c.

“If the Palmahim Slide is declared protected, these beautiful ecosystems could continue growing and provide a whole new frontier for research and exploration. With submersibles and robots, we can get pictures and videos of what goes on there,” she continues.

“As Sylvia Earle says, we can’t protect what we don’t know.”

Using new technologies, she says, “we can now find out tons of stuff about the deep sea. Fifteen or 20 years ago, you’d see this vast blue sea and not understand the amazing biodiversity it contains and how this affects our life here on Earth.”

One way it affects us is that the deep sea is a carbon sink, absorbing and sequestering some of the environmentally harmful carbon we create. A better understanding of this function could have implications for climate-change research.

“Instead of vast areas of sand and mud as you might expect, this area of deep sea with unique geological features is a complex area with different kinds of habitats where each animal can find its own niche,” says Gann-Perkal.

Life is slow-paced down here. Without the photosynthesis of the sun, plant life is nourished by chemosynthesis — nutrients carried gradually deeper on streams of water starting from the surface of the sea.

She notes that the Mediterranean covers about half of Israel’s area — 4,000 sq. kilometers of territorial waters and 22,000 sq. kilometers of exclusive economic zone (EEZ) waters. If the Hope Spot is declared a national marine reserve, it would be the first in Israel’s EEZ.

“The deep sea hasn’t been studied well, so it’s very exciting,” says Gann-Perkal. “It’s like exploring outer space. We need to bring back information from 1,000 meters under the sea.”