For such a small country, Israel sure boasts a huge number of ancient mosaics – some 7,000 of them, to be precise.

And those are just the ones that have been discovered and registered, with new archaeological digs or happy accidents regularly unearthing more ancient treasures.

The art of mosaics arrived in the Land of Israel from Rome around the time of Herod the Great 2,000 years ago. They were continuously created here through the 11th century, leaving us with documentation of Roman, Byzantine and early Arab culture in the area.

“Mosaics have an artistic component that tells of life during a certain period, about the mythology of the time, and there’s also a very strong element of aesthetics,” explains Jacques Neguer, the head of the Israel Antiquities Authority’s art conservation department.

“In addition, there’s also the information that appears in the inscriptions,” he says. “For example, the mosaic discovered at Megiddo Prison is probably the floor of the earliest church to have been found in the world and is a very rich source of information, both technological and artistic, as well as relaying information about the way people lived in that time period.”

The Megiddo mosaic bears many inscriptions, including the name of a lady who dedicated the altar to Jesus Christ, one of the earliest mentions of the name. The mosaic also features geometric shapes and a medallion with fish swimming at its center.

How old is it?

Neguer explains that the mosaics of the Land of Israel were influenced by the cultures surrounding it and the art coming from Egypt, Rome and Byzantium. Distinct styles emerged in different locations across the land.

Despite this great variety, many of the mosaics shared similar qualities, patterns and styles over the centuries – so much so that in many cases it’s not possible to date the mosaics based only on the artwork. Archeologists must make use of the surrounding digs and inscriptions to determine their age.

“There are many mosaics with geometrical patterns that get repeated for hundreds of years. You can recognize the same style of mosaic that moves on from a synagogue to a church and then to a public building. It’s the same sort of composition that transfers to different buildings,” Neguer says.

This repetition and transfer of style makes sense, he notes, since mosaic artistry was probably a profession passed down generations in a family.

Being a mosaic artist paid pretty well: in Roman times, a mosaic team manager earned 150 dinars a day, while a carpenter on a Roman navy ship earned only 60. The price of a chicken at the time was 30 dinars.

“They made a lot of money. They were free men and not slaves and their status in society was quite high,” Neguer says.

“But you have to take into account that making mosaics was very hard work. It included creating the materials, building the necessary infrastructure, cutting the stones, making a scale project and then the mosaic on site. By the end of the day your back would hurt.”

Another 200 years?

Fast forward 2,000 years, and the workload is now focused on preserving the endeavors of those ancient artisans.

Neguer notes that the mosaics that have been uncovered in Israel will probably last another 200 or so years until being ruined by wear and tear. Somewhat surprisingly, that’s not the end of the world as far as he’s concerned.

“First of all, you don’t preserve material, you preserve values,” he explains. “The conservation of the mosaics preserves the values and information that constitutes the mosaic and its archeological context.”

Originally, the mosaics’ condition began to deteriorate once they were put into use, for example as floors of buildings that were continuously stepped on and eroded. That ancient condition was preserved for as long as they were covered in earth. The real deterioration begins the moment they are discovered and exposed to people, climate change, vandalism, pesticides and natural erosion.

Neguer says, “Neglect is something that’s very typical to digs across the word. The right thing to do is to cover the mosaics inside the earth once again after the digs.”

Endangered by time

Back in 1994, Neguer and the Israel Antiquities Authority carried out a survey on 100 sites out of the 7,000 (encompassing around 30,000 square meters of mosaics) and determined that over 50 percent of them were in danger.

Conservation efforts since then have reduced that number to around 35%, with an additional 35% determined to be in good condition and the remaining 30% in moderate condition.

“We’ve worked very hard, for some 25 years, to reach this stage,” Neguer says.

The 50 or so mosaics that are situated in national parks are being looked after and enjoy maintenance and conservation work. The less famous mosaics and the ones in moderate condition can very quickly take a turn for the worse if they’re not cared for.

“There are less budgets for saving sites that have mosaics but that aren’t in tourist areas. Nobody’s interested in them,” he laments.

And while work is being carried out to preserve and even save sites of this kind, it requires continuous conservation work, maintenance and recovering in earth.

“The key for conservation is maintenance, it’s not only a one-time job,” he says. “You need to take care the whole time.”

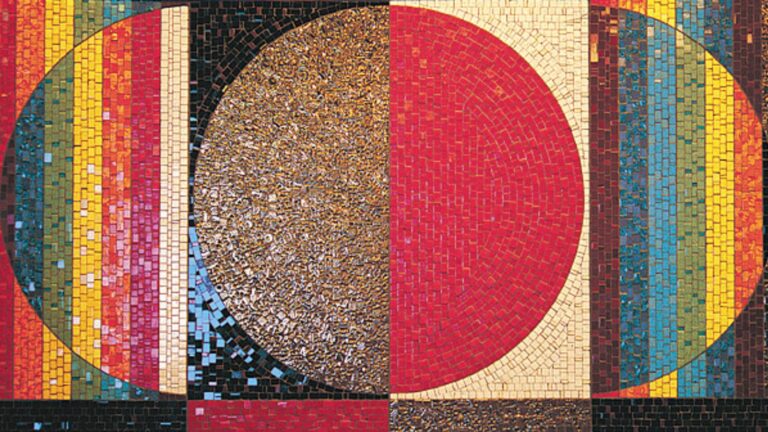

Having worked on countless mosaics throughout the country, Neguer has a personal favorite. Situated in Caesarea, it’s called the “golden table” or the “golden panel.”

The D-shaped mosaic did not serve as a mosaic floor but rather as an ornate tabletop. Its little squares and rectangles are made of thin layers of gold sandwiched between two layers of glass.

According to the experts, the glass-and-gold tabletop survived a fire that burned down the wooden table that it decorated. It was discovered lying face down on a mosaic floor at the villa.

“It’s not a big mosaic, just one meter by one meter, but it’s of such high quality. There’s simply nothing like it in the world. I enjoy being able to visit it at the Israel Museum,” he says.