Tiny “barcodes” made of synthetic DNA can help determine the suitability of specific anticancer drugs to a specific patient before treatment even begins, according to an Israeli study recently published in Nature Communications.

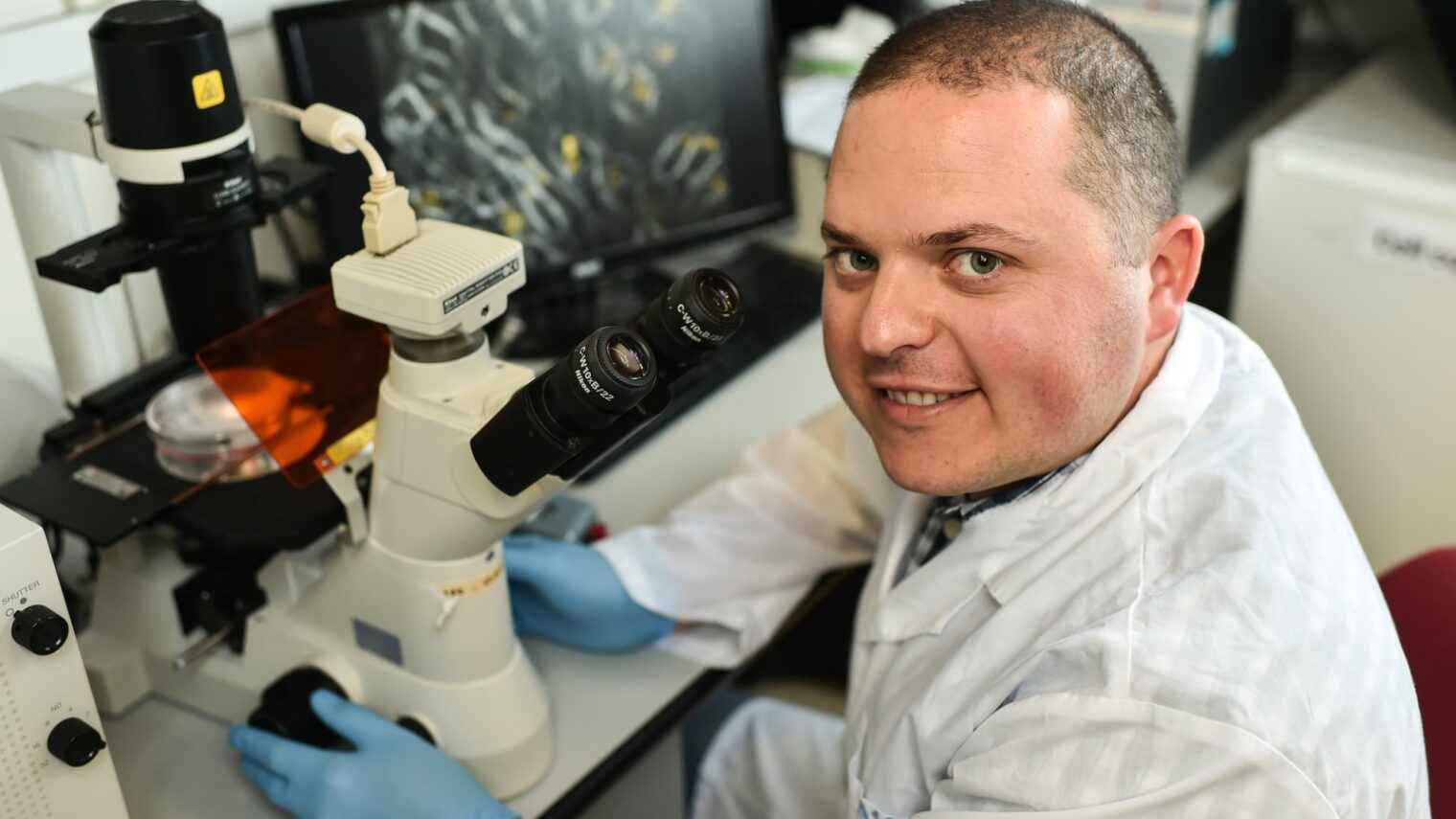

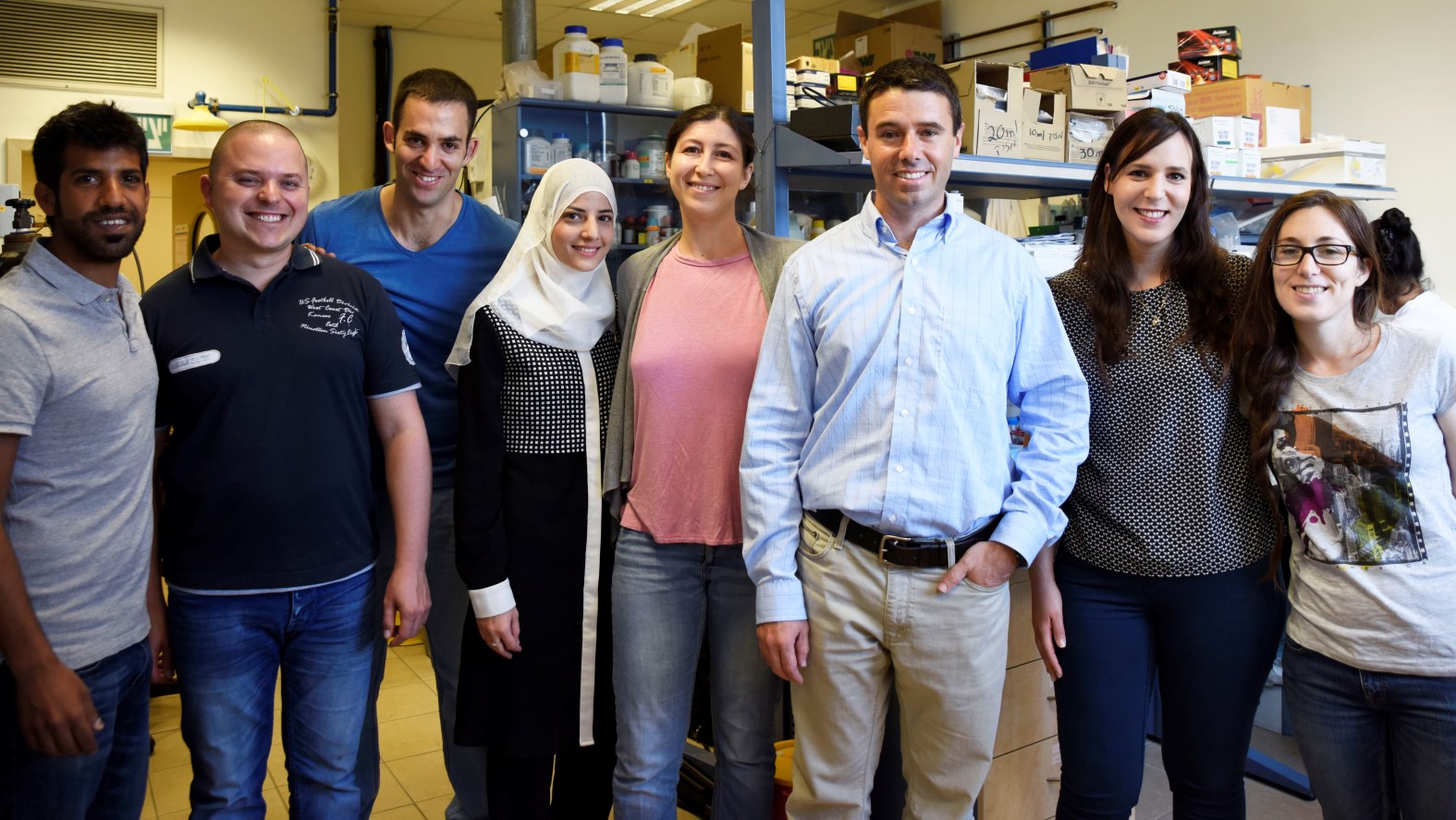

The new diagnostic technology was developed by Technion-Israel Institute of Technology researchers led by Assistant Prof. Avi Schroeder of the Faculty of Chemical Engineering and the Technion Integrated Cancer Center.

“The medical world is now moving towards personalized medicine, but treatments tailored only according to the patient’s genetic characteristics don’t always grant an accurate prediction of which medicine will be best for each patient,” explained Schroeder. “We, however, have developed a technology that complements this field.”

Together with doctoral student Zvi Yaari and other researchers, Schroeder created what amounts to a safe, miniature lab in each patient’s body to examine the effectiveness of a specific drug in that individual patient.

They attach synthetic DNA sequences to minuscule quantities of anticancer drugs, which they then pack inside specially designed nanoparticle vehicles for delivery to tumors. After 48 hours a biopsy is taken from the tumor and the tags serve as “barcode readers” of each drug’s activity in the cancer cells, showing how many malignant cells were killed.

The researchers are currently working with drugs registered as anticancer drugs, but in principle, they can test a battery of drugs for each patient and find out which is the most effective drug to treat his or her disease.

“It’s a bit like testing for allergies, where simple tests provide us with a specific person’s allergy profile,” Schroeder explained.

“Here we developed a simple test that provides us with a profile of the patient’s response to the designated drug. This method makes it possible to test the effectiveness of several drugs concurrently in the patient’s tumor, in minute doses not felt by the patient, and which do not pose any danger to him or her. Based on the test results, the most effective drug for the specific patient is selected.”

A few years to commercialization

The experiments were performed on lab mice with triple-negative type breast cancer, which does not respond well to standard treatment and presents difficulties for doctors to find the most effective drug for each patient.

“This technology provides a new window into fundamental insights about the mechanisms of cancer and resistance to various drugs,” said Schroeder. “But my thoughts are also practical: how our research could help people.”

The new technology was patented and now there are discussions regarding its commercialization. “It’s true that it’ll take a lot more work to turn our development into a product that’s available to the public, but I believe that we’ll see it at the clinic within a few years,” Schroeder predicted.

The study is being funded by a grant from the European Union and by the Israel Science Foundation and the Israel Cancer Association.

“We are proud to have supported such an important and promising research that could provide a customized solution for patients and lead to more efficient, precise and accurate treatment,” said Miri Ziv, director-general of the Israel Cancer Association.