The eye-catching gold ring on Miriam Siebenberg’s finger is a replica of a 2,000-year-old bronze key-on-a-ring excavated from underneath her home in Jerusalem’s Jewish Quarter. What did the key open? Siebenberg can only guess.

The ring was just the first indication that Theo and Miriam Siebenberg’s house, built on a hill in 1970, was sitting above an archeological site like a tiny cherry atop a layer cake filled with tantalizing ancient relics.

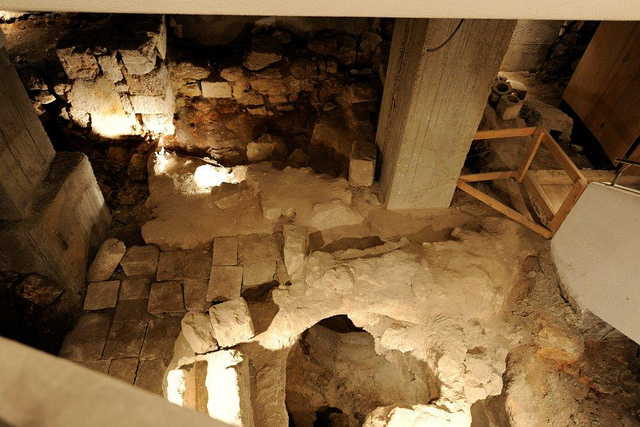

Underneath the four-story modern house, 18 years of digging revealed what Siebenberg calls “the perfect continuation of Jewish history in one place.” The base layer has emptied burial caves from the era of King David and King Solomon some 3,000 years ago.

Above that are the remains of a Hasmonean mansion inhabited by children of the Maccabees – the heroes of Hanukkah fame — who ruled Judea from 142-63 BCE after liberating it from the Syrian-Greeks.

This once grand abode is the showpiece of the subterranean museum that Biblical Archaeology Review called “an engineering and structural marvel,” open for group tours by appointment siebenberghouse@gmail.com.

‘Stones don’t talk’

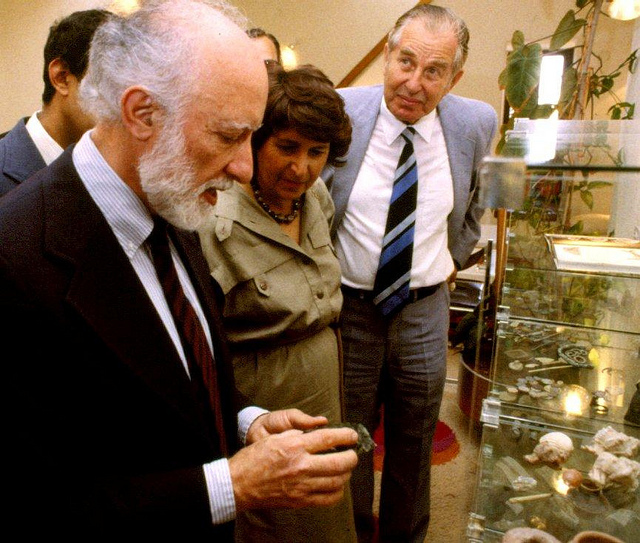

From the start, Theo Siebenberg strongly suspected that the site of his house must have been inhabited by Jews in the Second Temple period, given its proximity to the Temple Mount where the Holy Temples once dominated the skyline. He was assured that archeological surveys had not revealed anything of interest.

“But he insisted,” Miriam Siebenberg tells ISRAEL21c during a tour of the unusual museum.

Engineers advised the Siebenbergs first to support their newly built house by putting up a multi-section retaining wall with anchors each holding up to 60 tons of pressure. That process alone took eight years.

Half-hour tours of the house museum begin with a slide show depicting the ensuing excavation process.

The earth under the house was packed so densely that it amounted to five times the volume of the dug-out space, Siebenberg explains. Modern machinery couldn’t fit in the narrow alley outside, so all the dirt was lifted out manually in buckets, sifted for artifacts and carried on donkeys’ backs to waiting trucks.

The key ring was discovered first, followed by glass perfume bottles and bracelets; a device for spinning fine cotton thread; an ivory pen and inkwell; 2,600-year-old arrowheads probably made to fight off Babylonian invaders; and a glass drinking cup shaped like a horn of plenty – only seven cups like this have ever been found.

Also uncovered were two ritual baths, a large water cistern, a primitive stone faucet, a rare relief showing the three-legged First Temple menorah, a Seal of Solomon pentagram carving, and a bronze bell, which inspired the Siebenbergs to sponsor ongoing harp recitals in the space.

More than 80 TV crews have filmed stories at the site. Reporters from National Geographic, NBC and The New York Times were among those who interviewed the Siebenbergs during the excavations.

“I understood that in other archeological sites there are only stones, and stones don’t talk. Here, there was a person with a narrative,” says Siebenberg, a Tel Aviv native whose husband reached Israel 10 years after fleeing Nazi Europe.

The stones under his feet

Born in Antwerp, Theo Siebenberg always dreamed of living in the land of his forebears, but World War II stalled his plans.

At 13 years of age, in 1940, he fled Belgium with his family, eventually arriving in New York. He finally reached Israel in 1950. In 1967, when Jerusalem was reunited, he and his Israeli bride rushed to buy property in the Jewish Quarter.

“He was looking for his ancestral home,” Miriam Siebenberg says. “It was burning in his soul — not to prove anything, but to find his roots. He had the vision to see it right under his feet.”

Actual stones from the ancient mansion are piled along one wall. This is a rare cairn, she explains. Old 200-pound stones ordinarily are removed from archeological sites in pieces.

“My husband wanted to save them, so he brought special porters to carry them out to the lot next door, and when we finished the work they brought them back in to be in one place as a memorial to the Maccabee house that stood here 2,000 years ago,” says Siebenberg.

She points out black streaks on one of the support pillars erected at the start of the excavations. The streaks contain ashes from ancient dirt stirred up by the construction project and stuck in the wet concrete – presumably dating from the eighth day of the Jewish month of Elul (August 31) in the year 70 CE, when Roman legions burned down the Upper City of Jerusalem – now known as the Old City.

As for the burial crypts, they date back to when the Upper City was used as a cemetery for the neighboring City of David 3,000 years ago. In 750 BCE, when foreign conquerors exiled Jews from the northern kingdom of Israel, 5,000 refugees escaped southward and began building homes in the Upper City. They moved the remains from the burial chambers to another area, and purified the vaults to use for underground storage.

After more than four decades, Miriam Siebenberg still retains a sense of wonder about the tangible evidence of historical continuity that links her house to Jewish homeowners from 900 BCE.

“In other places you have excavations, but nobody lives on top,” she says.

For more information, click here.