“You shall live in booths seven days; all citizens in Israel shall live in booths, in order that future generations may know that I made the Israelite people live in booths when I brought them out of the land of Egypt” (Leviticus 23:42–43).

The holiday of Sukkot is one of three pilgrimage festivals when Jews went up to the Temple in Jerusalem to worship together as one nation. Then, as now, the Exodus from Egypt was memorialized by erecting a temporary structure, the sukkah (“booth” or “tabernacle”), and living within it under the stars, as did the Children of Israel.

Maintaining the Sukkot tradition in the Diaspora was not always easy, whether due to cold weather – so different to the pleasant fall harvest season of the Land of Israel – or to religious persecution that prevented Jews from honoring the holiday openly.

Small wonder that in modern-day Israel, immediately with Yom Kippur’s end, wooden tabernacles would spring up – like so many boxy declarations of religious liberty – in private and, more significantly, public areas where people can sit and eat in the mystical tradition of ushpizin or hosting guests.

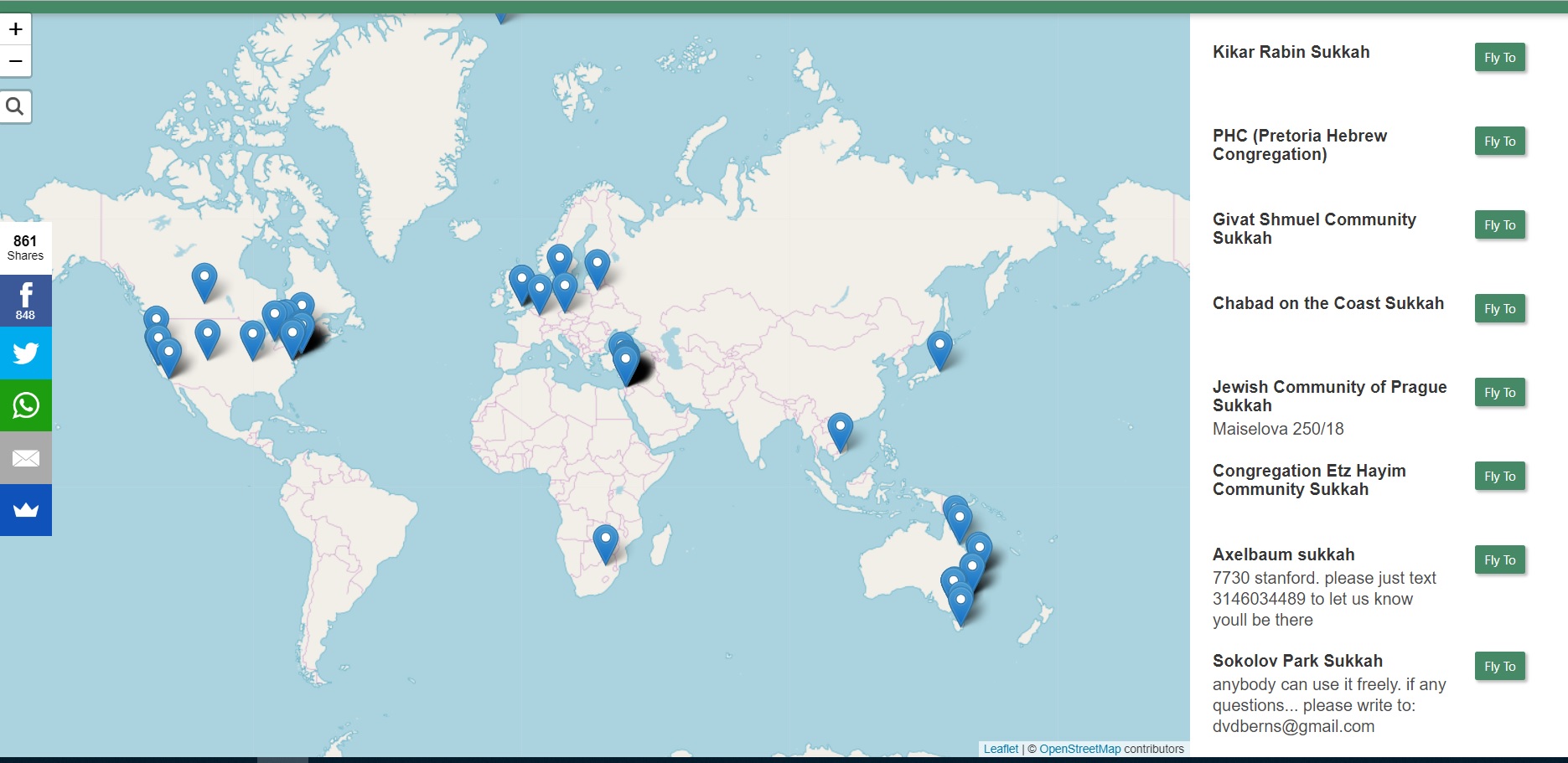

There’s even an app for that: Open Sukkah was launched last year by Canadian-Israeli computer programmer Aaron Taylor as a social database of sukkah locations around the world. Users can double-click on the Open Sukkah map to offer their sukkot to guests or to find a sukkah to host them.

But even before the advent of such high-tech solutions, there were ways for people to find a common place outside the home for fulfilling the commandment of sitting in the sukkah.

Between 1881 and 1934, the Photographic Department of Jerusalem’s American Colony — an independent, utopian Christian sect formed by religious pilgrims from the United States and Sweden – photographed every aspect of the Holy Land and its residents. This included documenting the sukkot built by the Bukharan, Yemenite and Eastern European Jews of Jerusalem.

During the Sukkot holiday of October 1934, an American Colony photographer documented the interior of the fabulously decorated sukkah at the Goldsmit House Hotel. According to the Encyclopedia of the Founders and Builders of Israel, the proprietor, Avraham Zvi Goldsmit (also Goldschmidt), was one of the pre-state pioneers of physical education. He turned hotelier with the advent of the British Mandate. His sukkah hosted guests of the hotel and its restaurant.

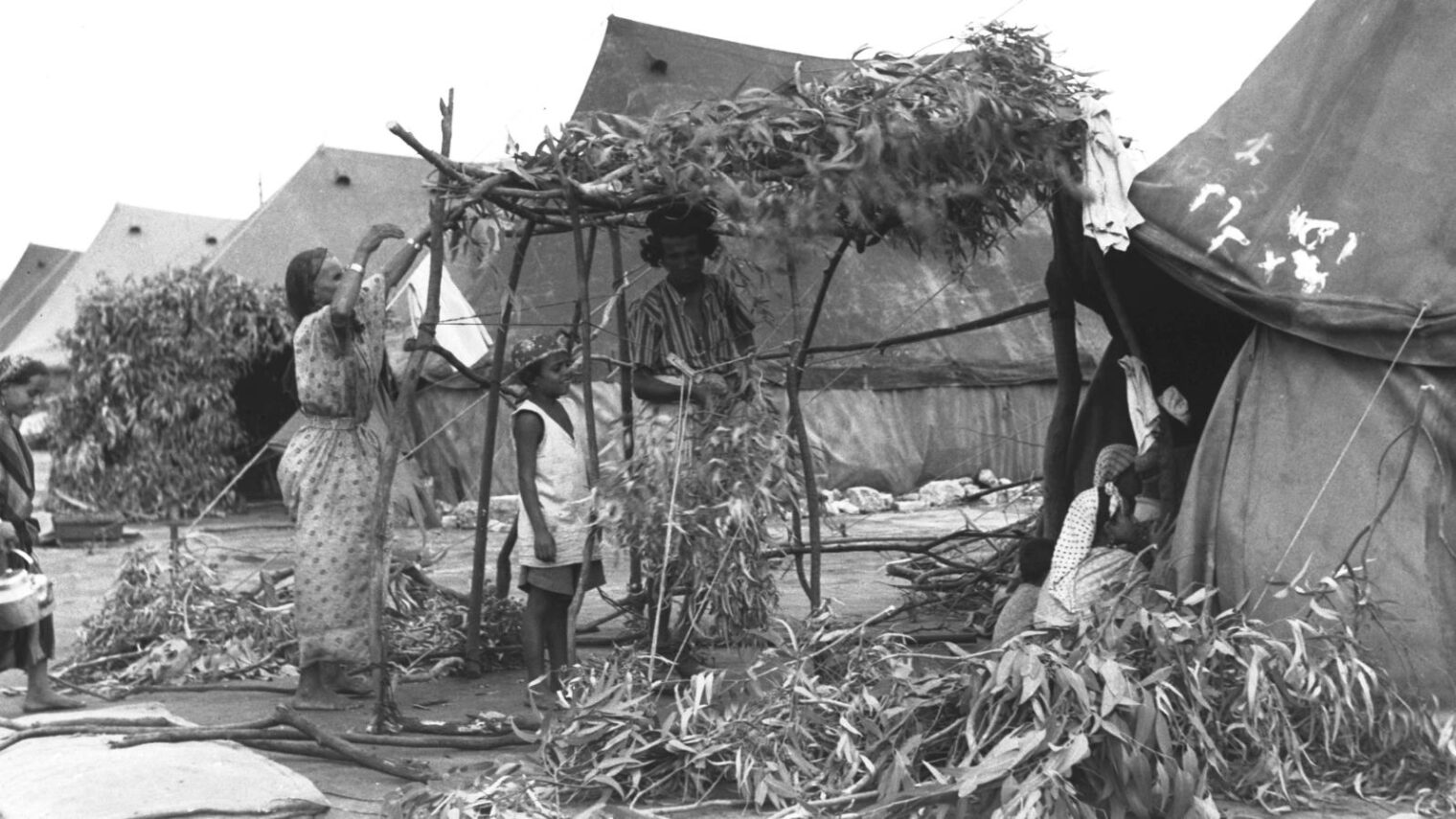

As the newly founded State of Israel struggled to absorb large numbers of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, North Africa and the Middle East, many ended up in shanty-towns (ma’abarot). Ironically, these newcomers celebrated their first Sukkot in Israel by building huts only slightly more flimsy than the provisional ones allotted to them.

As a communal harvest holiday, Sukkot was a natural fit for the kibbutz movement which, even in its most anti-religious phases, built sukkot adjoining their dining halls. Children built sukkot at their schools, and apartment-block residents often got together to build a neighborhood sukkah.

Till this day, one of the State of Israel’s nicest official Sukkot rituals is the annual President’s Open Sukkah.

Not to be confused with the ritual, now in its seventh decade, of tabernacle-centric political back-slapping and photo-ops, Open Sukkah offers an opportunity to visit the sukkah at the Presidential Residence in Jerusalem and possibly shake the hand of the beloved national figure.

The founders of co-working space pioneer WeWork were inspired by the kibbutz and by the North American communal movement of the 1960s. In that spirit, and to mark both the holiday and the opening of its first Jerusalem location, this year WeWork constructed a co-working sukkah in Jerusalem’s historic First Station.

The WeWork sukkah provides an “office away from the office” including free Wi-Fi access, lounge area, and two conference rooms. In keeping with the informal vibe, there’s a coffee bar and barista, and in the evenings, a bartender and DJ for some real “Sukkah hopping” action.

Much like Airbnb, Sukka2Go appeals to Israelis who may be away from home for the holiday, leaving their sukkah unused. They are invited to share the location as well as find hospitality via the Sukka2Go website.

A high-tech solution to fulfill an ancient commandment – there’s nothing more Israeli than that.

![Elections 1977 – Likud posters] In 1977, Menahem Begin led an election upset as Israel’s first non-Labor prime minister. Credit: GPO Elections 1977 – Likud posters] In 1977, Menahem Begin led an election upset as Israel’s first non-Labor prime minister. Credit: GPO](https://static.israel21c.org/www/uploads/2019/09/Elections_1977___Likud_posters_-_GPO-768x432.jpg)