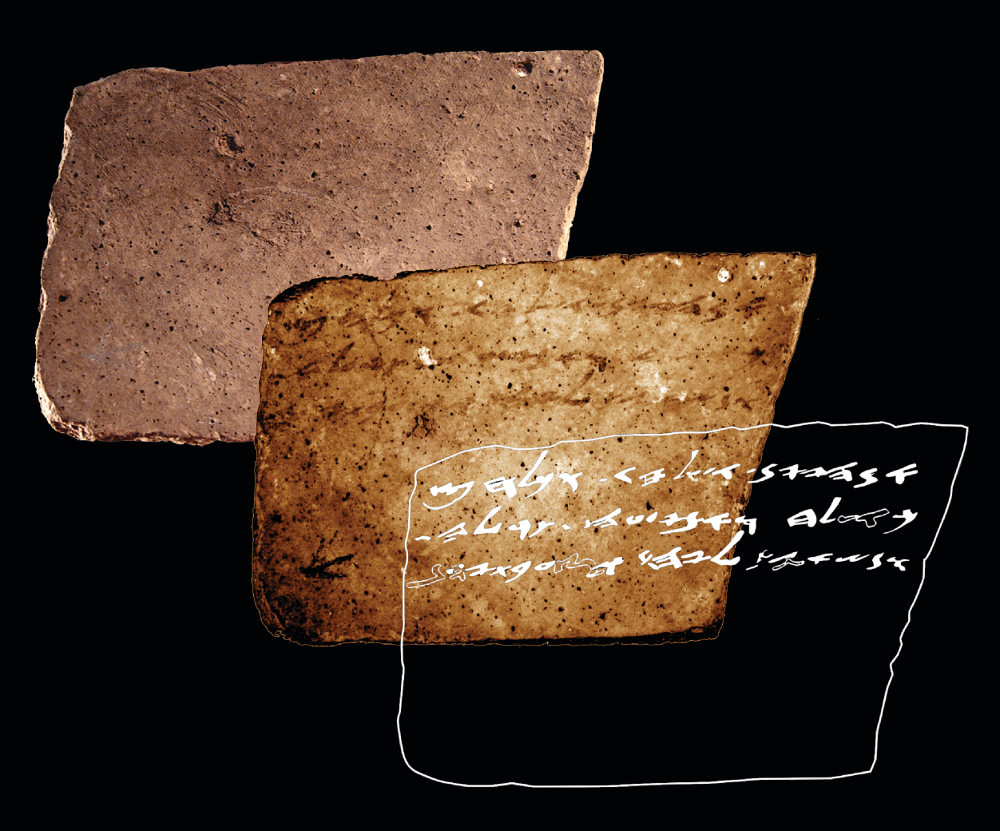

Israeli researchers have used advanced imaging technology to discover a hitherto invisible inscription on the back of a pottery shard that has been on display at The Israel Museum for more than 50 years.

The ostracon (ink-inscribed pottery shard) was first found in poor condition in 1965 at the desert fortress of Arad. It dates back to about 600 BCE, the eve of the kingdom of Judah’s destruction by Nebuchadnezzar. The inscription on its front side, opening with a blessing by Yahweh, discusses money transfers and has been studied by archaeologists and biblical scholars alike.

“While its front side has been thoroughly studied, its back was considered blank,” said Arie Shaus of Tel Aviv University’s Department of Applied Mathematics, one of the principal investigators of the study, published earlier this month in PLOS ONE.

“Using multispectral imaging to acquire a set of images Michael Cordonsky, of TAU’s School of Physics, noticed several marks on the ostracon’s reverse side. To our surprise, three new lines of text were revealed,” he said.

The researchers were able to decipher 50 characters, comprising 17 words, on the back of the ostracon. Using multispectral imaging, they were also able to significantly improve the reading of the front side, adding four ‘new’ lines. The content – administrative text – implied it was a continuation of the text on the front side.

“The new inscription begins with a request for wine, as well as a guarantee for assistance if the addressee has any requests of his own,” said Shaus. “It concludes with a request for the provision of a certain commodity to an unnamed person, and a note regarding a ‘bath,’ an ancient measurement of wine carried by a man named Ge’alyahu.”

At the time the ostracon was made, Tel Arad was a military outpost on the southern border of the kingdom of Judah, and was populated by 20-30 soldiers at a time.

“Most of the ostraca unearthed at Arad are dated to a short time span during the last stage of the fortress’s history, on the eve of the kingdom’s destruction in 586 BCE by Nebuchadnezzar,” said Dr. Anat Mendel-Geberovich, of Tel Aviv University’s Department of Applied Mathematics, who was also involved in the research.

“Many of these inscriptions are addressed to Elyashiv, the quartermaster of the fortress. They deal with the logistics of the outpost, such as the supply of flour, wine and oil to subordinate units,” she said.

“Its importance lies in the fact that each new line, word and even a single sign is a precious addition to what we know about the First Temple period,” she added.

“On a larger scale, our discovery stresses the importance of multispectral imaging to the documentation of ostraca,” said Shira Faigenbaum-Golovin, of the university’s Department of Applied Mathematics, another principal investigator of the study. “It’s daunting to think how many inscriptions, invisible to the naked eye, have been disposed of during excavations.”