How do 90 percent of advanced-stage melanomas (skin cancers) break through the blood-brain barrier and cause metastases in the brain?

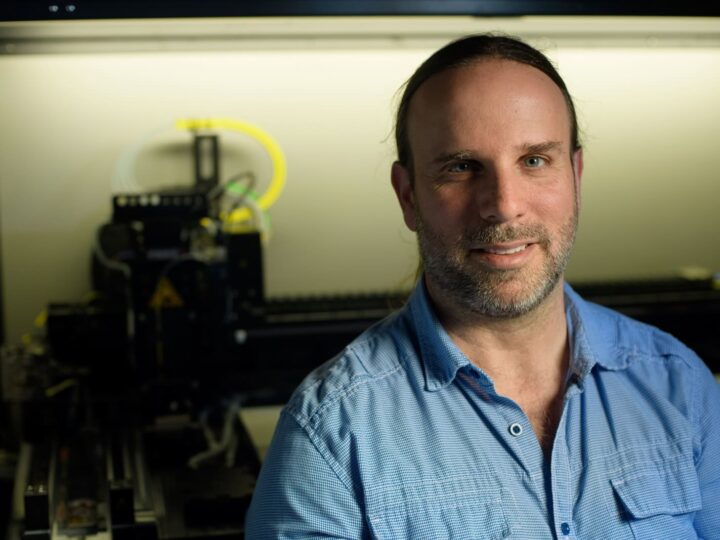

That was the question perplexing Tel Aviv University cancer biologist Prof. Ronit Satchi-Fainaro.

“This is a puzzling statistic,” noted Satchi-Fainaro. “We expect to see metastases in the lungs and liver, but the brain is supposed to be a protected organ. The blood-brain barrier keeps harmful substances from entering the brain, and here it supposedly doesn’t do the job – cancer cells from the skin circulate in the blood and manage to reach the brain. We asked ourselves with ‘whom’ the cancer cells ‘talk’ to in the brain to infiltrate it.”

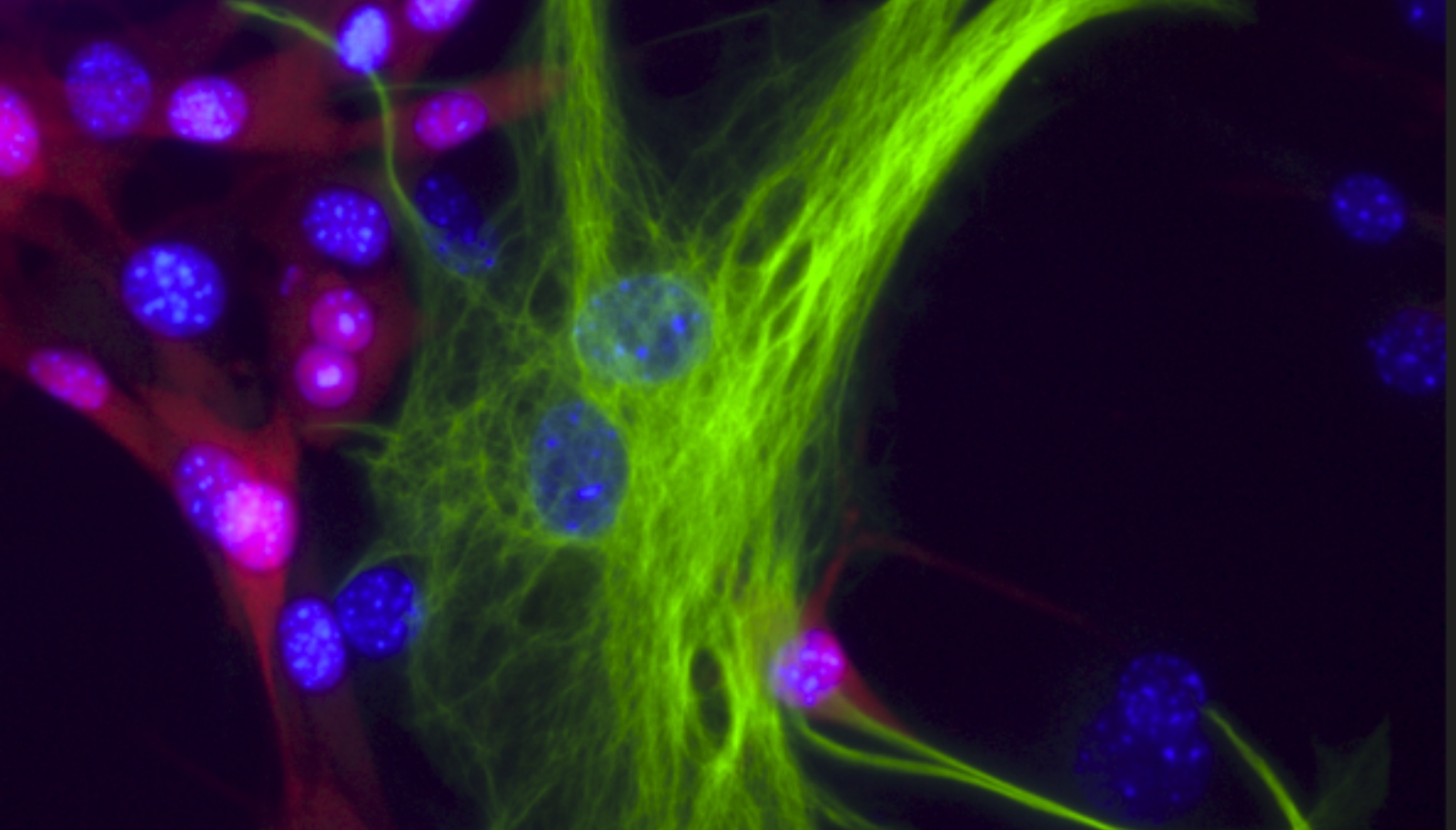

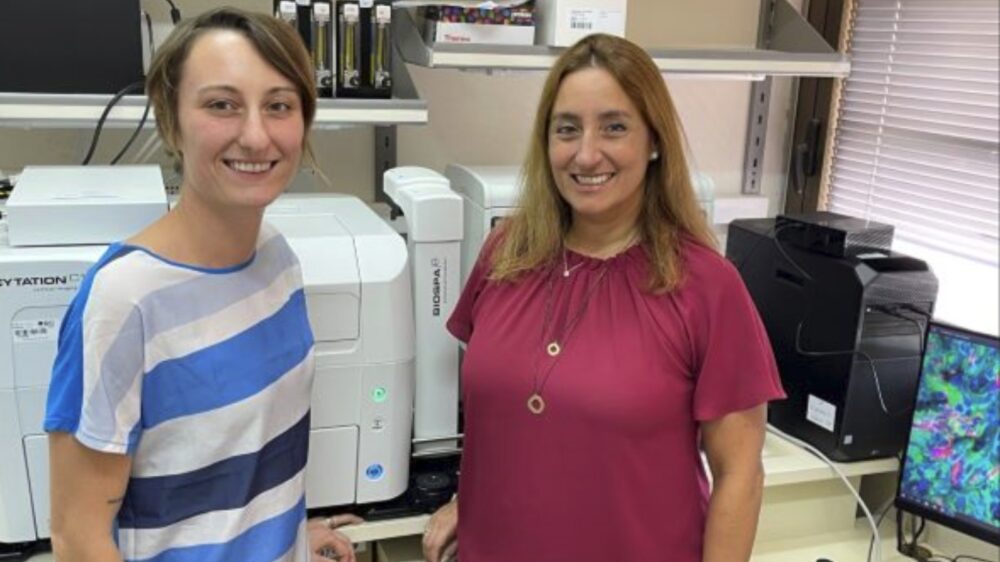

Satchi-Fainaro and PhD student Sabina Pozzi discovered that the cancer cells are talking to astrocytes, star-shaped cells in the spinal cord and brain responsible for maintaining stable conditions in the brain.

“The astrocytes are the first to come to correct the situation in the event of a stroke or trauma, for example,” said Satchi-Fainaro, “and it is with them that the cancer cells interact, exchanging molecules and corrupting them.”

When the astrocytes secrete a protein that promotes inflammation, the cancers cells begin to express receptors which, Satchi-Fainaro says “we suspected to be responsible for the destructive communication with the astrocytes.”

To test this hypothesis, the researchers inhibited the expression of this protein and the cancer cell receptors in genetically engineered lab models, as well as 3D models, of melanoma and brain metastases.

They used an antibody (a biological molecule) and a synthetic molecule designed to block the offending protein. They also employed CRISPR technology to genetically edit the cancer cells and cut out the two genes that express the relative receptors.

The result: The researchers were able to delay the spread of the metastases by up to 80%.

Their research is of critical importance, as melanoma metastases are particularly aggressive. Patients have a “poor prognosis of 15 months following surgery, radiation and chemotherapy,” Satchi-Fainaro noted.

The treatment, when applied immediately after surgery, prevented the metastases from penetrating the brain. “I believe that the treatment is suitable for the clinic as a preventative measure,” Satchi-Fainaro said.

Best of all, the antibody and the synthetic molecule already have been tested on humans and are considered safe. They are used to treat sclerosis, diabetes, liver fibrosis and cardiovascular diseases.

The research was conducted in collaboration with additional scientists and physicians from Tel Aviv University, the US National Institutes of Health, Johns Hopkins University and the University of Lisbon.

The study, published in the scientific journal JCI Insight, was funded by the European Research Council, the Melanoma Research Alliance, the Kahn Foundation, the Israel Cancer Research Fund and the Israel Science Foundation.