Hidden in plain sight, the Israeli jazz scene is exploding.

New York City’s Greenwich Village jazz scene – dominated in the 1960s by Afro-Cuban and Brazilian rhythms – now reverberates with the sounds of classically trained Israeli jazz musicians playing standards from the American songbook and creating their own style of jazz.

Bass player, bandleader and jazz educator Avri Borochov explains: “To become an Israeli jazz musician, I had the teachers, but there was also something here that is more than jazz — it is the Israeli culture.

“The geographic context, our neighboring countries, the sounds, the instruments, the oud, the different flutes, the drums, the story of the Jewish people, the sounds of my family.”

“It becomes Israeli jazz when our influences seep into our jazz. You want to really acknowledge where it comes from and you want to pay your dues,” says Avri’s brother, international jazz artist Itamar Borochov, who won the Rising Star Jazz Award in 2021.

Trombone player Yonatan Voltzok notes that Israel is a mishmash of cultures in which musicians try to define their identity and have an opportunity to express their roots through jazz.

“When I met jazz masters in New York they could recognize the things behind the notes that are more important than the notes themselves. Jazz is about paying respect to something higher, something that integrates,” he says.

New Israeli jazz orchestra debuts

Voltzok is CEO of the Pannonica Jazz foundation established by Yael Hadani in Tel Aviv in 2018 to encourage, assist and document Israeli jazz musicians.

Named for beloved 1960s New York City jazz patron Pannonica, granddaughter of the first Baron Rothschild, the foundation organizes concerts and international events and creates opportunities for musicians to represent the Israeli jazz scene abroad.

“Jazz in Israel has produced some of the greatest musicians I can think of,” Voltzok says.

The first project of Pannonica Jazz was assisting in the launch of a professional big band with original arrangements and a lot of original compositions.

Housed in the Lin and Ted Arison Israel Conservatory of Music (ICM) in Tel Aviv, the 18-piece Yonatan Voltzok Big Band orchestra debuted at ICM on November 17.

So many flavors

“You have so many flavors in Israeli jazz, and it is still evolving,” says Tel Aviv-based producer and jazz singer Neta Silbiger.

“Now, other non-Israeli musicians are trying to recreate these songs, which is great.”

Whenever Silberger speaks to people in the jazz industry abroad, they always ask her: “Do you know [trumpetist] Avishai Cohen? Do you know [saxophonist] Eli Degibri?”

She smiles. “And of course, I know all of them; they are my teachers and my colleagues. We sit here and talk whenever they are around [and they perform here].”

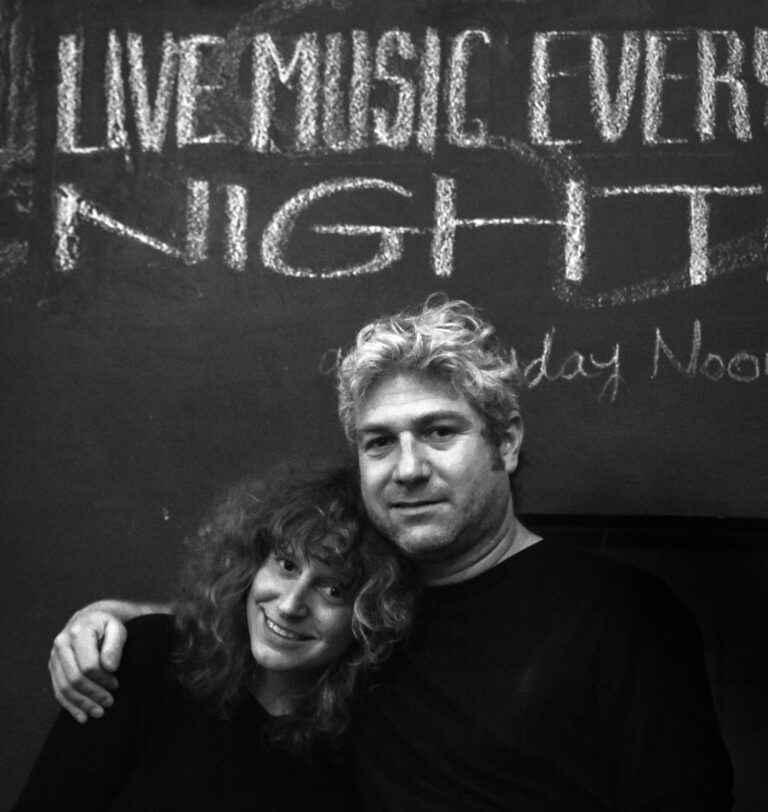

The “here” Silberger refers to is Tel Aviv’s Beit HaAmudim, where she spoke with ISRAEL21c along with Hadani, who helped Beit HaAmudim owner Eran Kol transform his café into Israel’s “jazz temple” in 2011.

The club marked its 10th anniversary on December 13, 2021, with a recreation of “A Great Day in Harlem,” an iconic 1958 group portrait of 57 New York jazz musicians.

Jazz sets at Kol’s café became weekly and then daily events. Every night, from Saturday to Thursday, there are three sets played, divided into two ensembles. On Fridays, sets are played at 1:30 and 3pm.

On the Sunday evening ISRAEL21c visited Beit HaAmudim, the Dan Gottfried Trio was playing.

Gottfried, one of Israel’s jazz pioneers, became obsessed at age 16 with the then-current sound of 1950s vinyl recordings of legends such as Canadian jazz pianist Oscar Peterson.

With no one in Israel to teach him, Gottfried learned by imitating what he heard, and by 1980 had become a renowned jazz pianist.

He went on to found the jazz department at the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance and initiated the still-popular annual Red Sea Jazz Festival in Eilat, which he ran for just over two decades.

ABCs of Israeli jazz

Today there are no barriers to studying jazz in Israel because there are plenty of trained Israeli musicians wanting to “give back.”

“If I know the ABC, my obligation is to teach it,” Voltzok says. “In jazz we have an obligation to share knowledge, to pass it on.”

In June, Pannonica organized a community fundraiser to create a fully funded jazz program for 14- to 19-year-olds in memory of the late Erez Barnoy, world-renowned saxophonist and director of the Center for Jazz Studies at the Tel Aviv Conservatory.

The Center for Jazz Studies has an academic collaboration with the New School in New York thanks to the late great saxophone player Arnie Lawrence, founder of the New School’s jazz department, who moved to Jerusalem in 1997.

Similarly, the Rimon School of Music in Ramat Hasharon has an academic collaboration with the Berklee College of Music in Boston thanks to a group of Israeli Berklee graduates who returned to Israel to found the Rimon School in 1985.

One member of that group, jazz saxophonist Amikam Kimelman, now directs an elite jazz program at Nofei Habesor, a high school in the Negev that has graduates going straight into the second year at Rimon or the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance.

“Jazz is a niche because the musicians have to be classically trained,” says Kimelman, who is musical director of the Tel Aviv Jazz Orchestra, the Jaffa Jazz Festival and the record label Jazz 972.

Making jazz Israeli

Gaby Frank, one of the Israelis who had immersed themselves in the Greenwich Village jazz scene and started moving back to Israel in the late 1990s to form bands and teach jazz, was Itamar Borochov’s first trumpet teacher.

In his early 20s, he was playing gigs at Hagada Smalit, (LeftBankTLV), where Israeli jazz greats such as bassists Omer Avital and Avishai Cohen, trumpetist Avishai Cohen and clarinetist Anat Cohen played.

“Every time they would come to Israel, we would go to see them perform there,” says Itamar.

Itamar’s brother Avri recalls listening to returning jazz musicians such as Jess Koren, Mamelo Gaitanopolous and the late Amit Golan playing in Tel Aviv cafés.

“They then became my teachers,” he says. “All of a sudden, my friends and I were listening to Blue Notes records and American saxophonists Charlie Parker and James Brown. We transcribed them and fell in love with the language.”

Avri began to explore incorporating Eastern and African sounds into jazz, and then he heard an Avishai Cohen album and understood there was already a “very Israeli accent and Israeli approach with Eastern and cool harmonies.”

In 2005, inspired by Cohen and Avital, Avri departed for five years of study in New York City.

Itamar, too, finished his musical education at the New School in New York, where he attended workshops led by jazz pianist Barry Harris, whose former students included Kurt Cobain.

“I was trying to learn music at the source,” says Itamar. “Black influence, US history, all the nuances that go along with it.”

The brothers discovered that their own heritage had something to offer. Itamar and Avi’s father, renowned jazz and world musician Yisrael Borochov, had infused them with knowledge of other musical disciplines, such as melodies from the synagogues of Uzbekistan.

Incorporating those influences into his original compositions, says Itamar, “builds jazz bridges.”

Click here to see French photographer Raphael Perez’s portraits of Israeli jazz musicians, soon to be released in book form.