How did Israel, a country that is more than half desert, frequently hit with drought, and historically cursed by chronic water shortages, become a nation that now produces 20 percent more water than it needs?

Water demand from Israel’s rapidly growing population outpaced the supply and natural replenishment of potable water so much that by 2015, the gap between demand and available natural water supplies reached 1 billion cubic meters (BCM).

Recovering from such a scenario seems highly unlikely, yet Israel managed it by pioneering an unprecedented wealth of technological innovation and infrastructure to prevent the country from drying up.

Nationwide turnaround stories like this are in short supply these days given the momentum of global warming and the world’s unwillingness to scale the solutions needed to thwart its irreversible effects in time.

Some 4 billion people –– two-thirds of the global population — now experience extreme water scarcity for at least one month out of each year due to the climate crisis.

But thanks to its national prioritization and seven decades of relentless determination, Israel has become a lifeline and source of hope for other water-deprived countries.

Israeli organizations like MASHAV, KKL-JNF, EcoPeace Middle East and the Arava Institute actively disseminate Israel’s expertise, technologies and policy strategies with neighboring and distant communities suffering from endemic water crises.

Breaking ground

Israel’s leadership in sustainable water management began with finding solutions to the country’s first and foremost problem: the uneven distribution of freshwater throughout the country –– an issue that Zionist thinker Theodor Herzl recognized in his 1902 book Altneuland with a “fantasy plan” to transport water great distances.

That fantasy began morphing into reality soon after Israel declared its independence in 1948 as waves of new immigrants lacked sufficient water for drinking and farming.

To supply the growing demand, Israel’s national water company Mekorot, began constructing the National Water Carrier.

This water transportation network was designed to pump water from the northern Lake Kinneret (Sea of Galilee) and transfer water from existing regional water projects to central and southern Israel.

But upon its completion in 1964, 80% of the water transported by this system was allocated for agriculture. Clearly, the National Water Carrier alone could not satisfy both agriculture and household needs.

Luckily, a solution was already in development thanks to the innovative genius of Simcha Blass and his son Yeshayahu, who began developing a drip irrigation technology in 1959. Their revolutionary method slowly applies water directly to the roots of crops through a network of tubes, valves and drippers.

Because this delivery method avoids the full brunt of evaporation, plants absorb 95 percent of the water applied to them – much more than sprinkler irrigation, surface irrigation or flood irrigation. With drip irrigation, less water could be allocated to farms without compromising agricultural output.

By 1965, the year following the completion of the National Water Carrier, Blass and his son began distributing their novel drip irrigation system throughout Israel and established Netafim, still a world leader in the field.

Today, drip irrigation waters 75% of Israel’s crops, but only 5% of farms worldwide currently utilize the technology due to financial barriers.

Using the unusable

Despite the transportive advantages of the National Water Carrier and the conservation benefits of drip irrigation, both innovations drew water solely from Israel’s very limited freshwater sources, which were being pumped faster than they could be naturally replenished.

Plus, the share of freshwater devoted to agriculture still vastly outweighed the amount allocated for drinking. By the mid-80s, agriculture was using 72% of Israel’s safe water supply.

Israeli engineers realized it’s not just about conserving available freshwater but also taking advantage of water sources previously considered unusable, such as treated municipal wastewater and stormwater.

In 1985, Israel began sending treated, recycled wastewater through its National Water Carrier to farms, greatly reducing the gap between consumer demand and available water.

This is because wastewater from our sinks, showers and toilets is not dependent upon climate fluctuations or seasonal weather patterns, but rather on population growth and living standards.

By 2015, Israel had managed to treat and recycle 86% of its wastewater for agricultural operations, leading the world in wastewater reclamation. Second to Israel in that same year was Spain, recycling just 17% of its wastewater.

Through Israel’s tertiary treatment processes, recycled wastewater is cleaned to near drinking-quality levels before reaching crops to avoid contamination.

The goal is to recycle 95% of wastewater for agriculture by 2025, leaving that much more fresh drinking water for the communities that need it.

Reclaimed and desalinated water

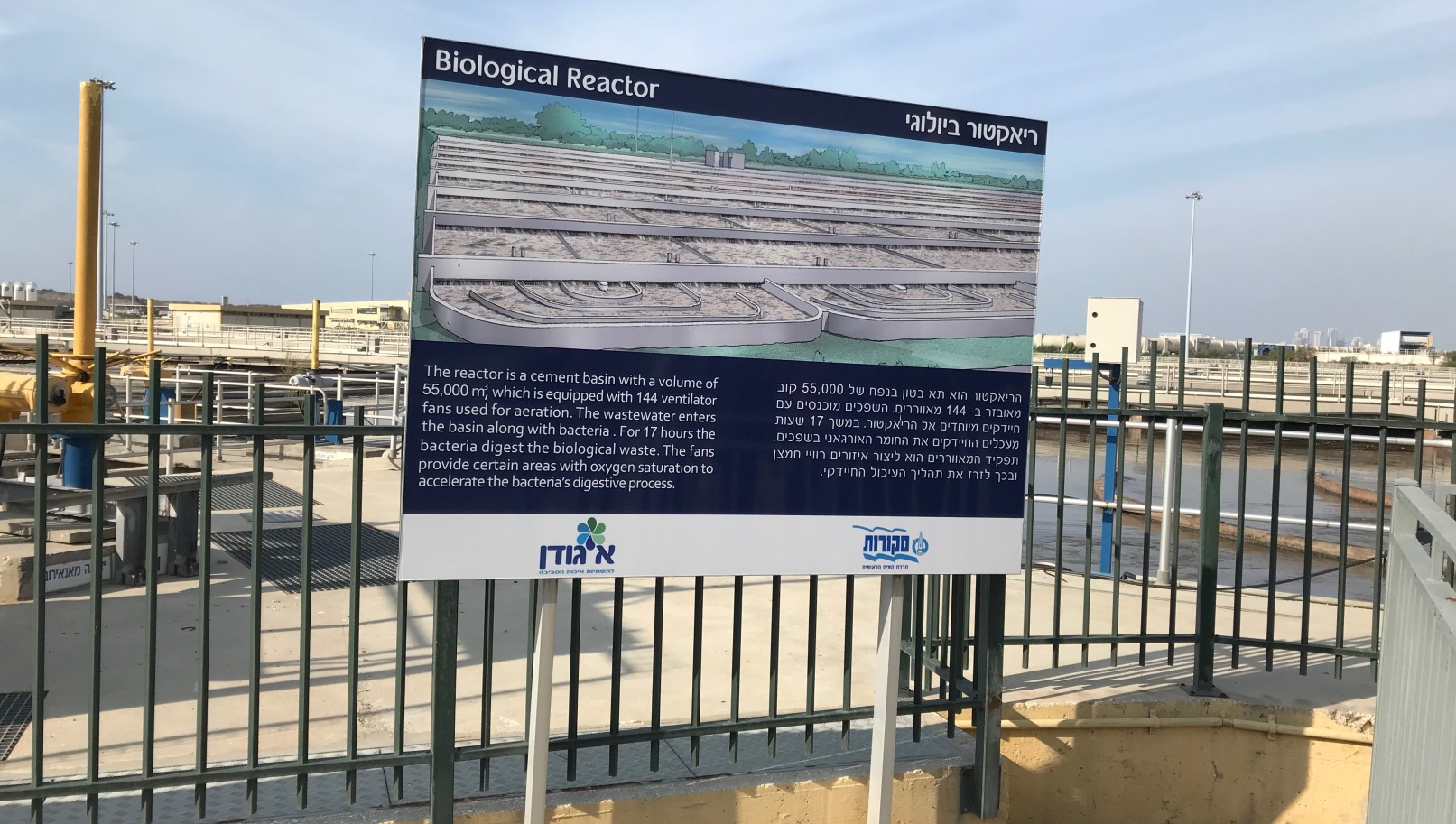

With a daily influx of roughly 470,000 cubic meters of raw sewage, the Shafdan treatment facility, Israel’s largest wastewater treatment facility, provides about 140 million cubic meters (MCM) of clean, reclaimed water to Negev desert farms for irrigation annually. In fact, more than 60% of agriculture in the Negev is supplied by Shafdan alone.

On top of that, the Israeli green development organization KKL-JNF constructed 230 reservoirs that store treated wastewater for agricultural use. Every year, these reservoirs add upwards of 260 MCM of water to Israel’s water economy.

KKL-JNF also established several biofilter projects in which plants remove nearly 100% of pollutants from urban stormwater runoff to enable an additional source for non-drinking municipal water and agricultural irrigation.

By 1997, Israel had managed to reduce agriculture’s share of water to 63 percent, yet persistent droughts in the mid-90s made Israel turn its attention to the surplus of seawater along its Mediterranean coast.

In 1999, the Israeli government initiated a long-term, large-scale seawater reverse osmosis desalination program that culminated in the establishment of five operational desalination facilities: the Ashkelon Plant (2005) capable of producing 118–120 MCM of potable water per year; Palmachim (2007), which now produces 90-100 MCM of water per year; Hadera (2009) capable of producing 127 MCM of water per year; Sorek (2013), which produces 150 MCM of water per year; and Ashdod (2015), which produces 100 MCM of water per year.

Israel has two more desalination plants in development, one of which is aimed to be operational by 2023. They will have a combined capacity of 300 MCM per year.

Upon completion of the seventh facility, desalinated water will cover up to 90% of Israel’s annual municipal and industrial water consumption.

To remain resilient in the drought-projected years to come, the Israeli government in 2018 updated its desalination with a target to produce 1.1 BCM of desalinated water by 2030.

Israel’s per capita consumption of renewable fresh natural water shrank dramatically from 504 MCM in 1967 to 98 MCM in 2015 — the year that desalinated and recycled water accounted for nearly half of Israel’s water consumption.

A cultural innovation

Israel continues to improve the efficiencies, filtration and production capacities of its water conservation portfolio with many upgraded technological systems and regional agreements.

But technology must be accompanied by controlled consumption habits, or else a country could risk exhausting its resources or incurring a shortage no matter how sustainably it supplies its water.

Because Israel’s chronic water struggles were felt by Jewish settlers even before the foundation of the state, the value of saving water quickly became second nature.

In the midst of consecutive droughts throughout the 2000s, the Israel Water Authority launched awareness campaigns via TV, radio and Internet urging the public to save water.

One such campaign was aimed at children through a series of cartoon television programs that taught the importance of saving water through simple means, nurturing generations of conscientious citizens.

The most significant awareness campaign came in 2009 and featured Israeli celebrities Ninet Tayeb, Bar Rafaeli and Moshe Igvy speaking honestly about the declining water levels of the Kinneret and the dire need to consume water in moderation.

As they spoke, their facial features began to crack and peel. This made water scarcity personal and led to an 18% reduction in water consumption in urban areas.

The combination of high-tech solutions and national cultural awareness truly distinguishes Israel’s water conservation program from so many others.

Israel succeeded in securing its water economy because the gravity of the situation was understood by all, from Israel’s leaders to its citizens.

Although it will likely be more expensive and difficult to scale similar infrastructure and solutions in areas like California, which needs more than 11 trillion gallons of water just to catch up with its current deficit, Israel shares its expertise internationally.

For countries struggling to expand or even begin water conservation strategies, Israel is a key global player in helping the world make the most of its water supplies.