New evidence found in ancient Judean clay jars shows Earth’s geomagnetic field has been fluctuating for thousands of years and that there is no reason to be worried about its current welfare, even though it is diminishing and some scientists suspect it is about to flip.

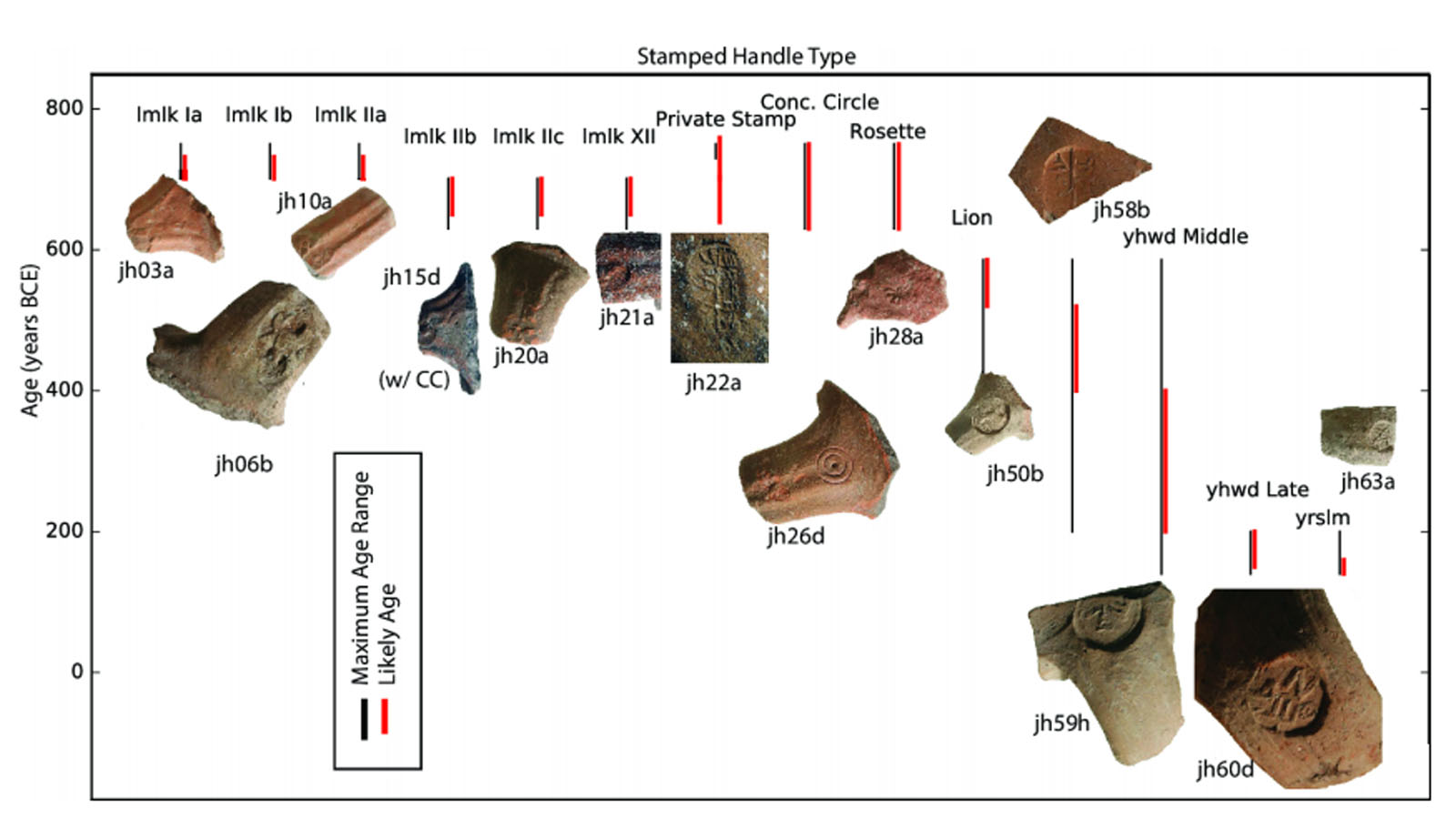

In a new study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), researchers from Tel Aviv University, Hebrew University of Jerusalem and University of California-San Diego cite data obtained from the analysis of 67 well-dated Judean jar handles.

These heat-impacted ceramic pots, which bear royal stamp impressions from the eighth to second centuries BCE, show evidence of changes in the strength of the geomagnetic field over the years.

“The period spanned by the jars allowed us to procure data on the Earth’s magnetic field during that time — the Iron Age through the Hellenistic Period in Judea,” said Erez Ben-Yosef of TAU’s Institute of Archaeology, the study’s lead investigator.

Scientists don’t entirely understand the function of the geomagnetic field, but some suspect there’s a correlation between magnetic pole flips, which leave the planet vulnerable to cosmic radiation, and mass extinctions.

“This new finding puts the recent decline in the field’s strength into context. Apparently, this is not a unique phenomenon – the field has often weakened and recovered over the last millennia,” said Ben-Yosef.

“The typology of the stamp impressions, which correspond to changes in the political entities ruling this area, provides excellent age estimates for the firing of these artifacts.”

The field was shown to peak during the eighth century BCE, which Ben-Yosef said “corroborates previous observations of our group, first published in 2009, of an unusually strong field in the early Iron Age. We call it the ‘Iron Age Spike,’ and it is the strongest field recorded in the last 100,000 years.”

Natural clay measurement

To accurately measure geomagnetic intensity, the researchers – Ben-Yosef, Oded Lipschits and Michael Millman of TAU, Ron Shaar of Hebrew University and Lisa Tauxe of UC-San Diego — conducted experiments at the Paleomagnetic Laboratory of Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC-San Diego, using laboratory-built paleomagnetic ovens and a superconducting magnetometer.

“Ceramics, baked clay, burned mud bricks, copper slag — almost anything that was heated and then cooled can become a recorder of the components of the magnetic field at the time of the event,” said Ben-Yosef.

“Ceramics have tiny minerals – magnetic ‘recorders’ – that save information about the magnetic field of the time the clay was in the kiln. The behavior of the magnetic field in the past can be studied by examining archaeological artifacts or geological material that were heated then cooled, such as lava.”

Advanced dating method for archaeological artifacts

The researchers say their new findings will benefit both the fields of archaeology and earth science.

They show, in their study, how changes in the geomagnetic field can be used as an advanced dating method complementary to radiocarbon dating.

“The improved Levantine archaeomagnetic record can be used to date pottery and other heat-impacted archaeological materials whose date is unknown,” said Ben-Yosef.

A deeper understanding of “proxies like the magnetic field, which reaches more than 1,800 miles deep into the liquid part of the Earth’s outer core,” say the researchers, will give “a clearer picture of the planet and its inner structure.”

The researchers are currently working on enhancing the archaeomagnetic database for the Levant, one of the most archaeologically rich regions on the planet, to better understand the geomagnetic field and establish a strong dating reference.