In 2006, Eran Levin entered an abandoned bunker on the Israel-Jordan border and saw a colony of bats hanging from cables and from metal shelves full of old cigarette packs.

Levin had found his missing link.

Then a PhD student, he was studying bats in the Judean Desert. He knew that after mating in April, greater mouse-tailed bats begin migrating north to the Sea of Galilee and Hula Valley.

But where did they stop on the way? He and Aviam Atar from the Israel Nature and Parks Authority (INPA) decided to look for roosts in the Jordan Rift Valley.

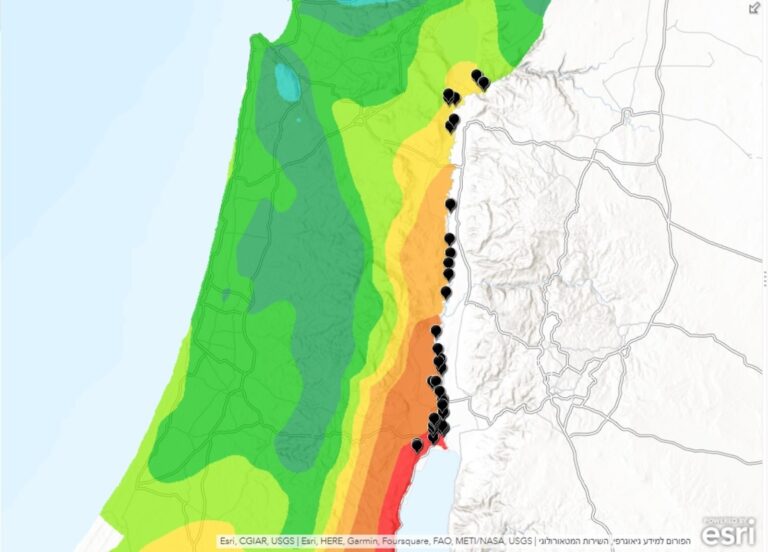

More than 40 Israel Defense Forces bunkers lie under a narrow strip of no-man’s land between the border fence and the Jordan River, stretching 60 miles from the Dead Sea to Sea of Galilee.

Abandoned after Israel and Jordan signed a peace treaty in 1994, these roughly 13-by-40-foot underground shelters have become a haven for thousands of diverse bats in a model of peaceful coexistence.

“This is the only place in the world where you find tropical, desert and European species of bats together in one group,” Levin tells ISRAEL21c.

“It’s really peace in the Middle East. Any bat expert who sees this picture cannot believe it. What makes it possible is the very specific conditions in these bunkers.”

Bunkers into bat houses

Those conditions weren’t perfect until Levin and Atar intervened.

Normally, bats hang from cave ceilings. With more and more caves disturbed by humans, Israel’s dwindling bat population found shelter in the concrete bunkers. But the ceilings weren’t right for roosting, leaving the flying mammals clinging to cables and shelves.

“It really looked uncomfortable,” says Levin, now director of the Nutritional Ecology Lab at Tel Aviv University’s School of Zoology.

“Our idea was to transform these bunkers into bat houses. All the authorities were against this idea at first. But finally we got permission from the IDF and support from Bat Conservation International’s Global Grassroots Conservation Fund.”

First, they cleared away trash and objects obstructing the entrances so that more bunkers could be inhabited by bats. (One bunker that was unblocked only in 2016 is now home to 100 bats.)

Then they covered the slick metal ceilings with bat-friendly materials that give the animals a rough surface they can grasp securely.

“We did this by applying plaster mixed with gravel, attaching plastic mesh, installing simple wood structures, stretching ropes or spraying a layer of lumpy, polyurethane foam,” says Levin. “And immediately they started using these structures.”

The only successful artificial bat roost

The bat population in the bunkers has been rising steadily. The first counting in 2014 totaled 2,311. By 2021, the bats numbered 7,380.

“This is the only known project of artificial bat roosts that is really working,” Levin tells ISRAEL21c.

“A whole ecological system has developed around them. Snakes feed on the bats and many invertebrates feed on the bat feces.”

Moreover, the bunker bats provide natural pest control for farmers on both sides of the Jordan River. Except for the Egyptian fruit bat, all the species here eat insects.

The project also has gotten support from the Society for the Protection of Nature in Israel (SPNI), INPA and the Jerusalem Biblical Zoo.

A LiDAR scan video recorded inside one of the bunkers was shown in the Israeli Pavilion at last year’s Venice Architecture Biennale.

Goldmine of data

Bunker bat colonies provide a goldmine of data for scientific study.

“There are endless questions we can ask about competition, evolution, physiology. My specialty is understanding how animals adapt to their environments,” Levin tells ISRAEL21c.

“The bunkers are built along a climate gradient from rainy in the north to extreme desert in the south, but they are all exactly the same – built underground with tunnels — so that makes it interesting for research.”

The 10 species inhabiting these bunkers range from critically endangered to vulnerable. Among them is the only known colony of Egyptian slit-faced bats in Israel. Lesser mousetail bats, the most common species in the bunkers, use their very long tails like a visually impaired person’s white cane to feel their environment.

“We’ve been ringing them – attaching bands to their feet — for the past 15 years so we know they live at least that long because we keep catching the same bats,” says Levin. “We’ve also learned a lot about their social structure and foraging behavior and diet. Now we’re now doing genetic research.”

The Nature Defense Force

The bunker bat project is one of about 60 under the umbrella of Nature Defense Forces, a partnership formed in 2014 by the IDF, SPNI, INPA and the Israel Antiquities Authority to encourage army commanders to take responsibility for the environment in military zones throughout Israel.

SPNI’s Guy Saly manages this initiative. He says commanders can “create an actual change in the territories they’re responsible for” by reducing hazards to wildlife such as forest fires, bird strikes and illegal poachers.

He explains that areas allocated for Israel’s security needs take up over half of state lands, and IDF bases and firing zones are often sanctuaries for endangered species.

Saly says the commanders in the military zone between the border fence and the Jordan River assign soldiers to help Levin’s team do annual population surveys of the bats.

Since commanders change frequently, sometimes it’s challenging for Levin to get permission to access the bat bunkers. On the other hand, the bats are safe from unwanted human visitors on either side.

Saly invited Jordanian army officials to see the project and then the Israelis were invited to Jordan to look for roosting bats there.

“We went to Jordan to look for bat bunkers, but the Jordanians never built underground bunkers, just trenches,” says Levin. “So all the bats are on the Israeli side, but they go to feed on the Jordanian side.”

“It’s a nice example of cooperation between the two armies,” concludes Saly. “The bats don’t know there is a border.”