Artificially activating the “reward system” in the brains of mice with two types of cancer led to a dramatic reduction in the size of their tumors, according to authors of a study conducted at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology.

“The relationship between a person’s emotional state and cancer has been demonstrated in the past, but mainly in relation to negative feelings such as stress and depression and without a physiological map of the action mechanism,” said Assoc. Prof. Asya Rolls of the Technion Rappaport Faculty of Medicine, who supervised the study.

“Several researchers, for example Prof. David Spiegel of the Stanford University School of Medicine, showed that an improvement in the patient’s emotional state may affect the course of the disease, but it was not clear how this happened. We are now presenting a physiological model that can explain at least part of this effect,” she said.

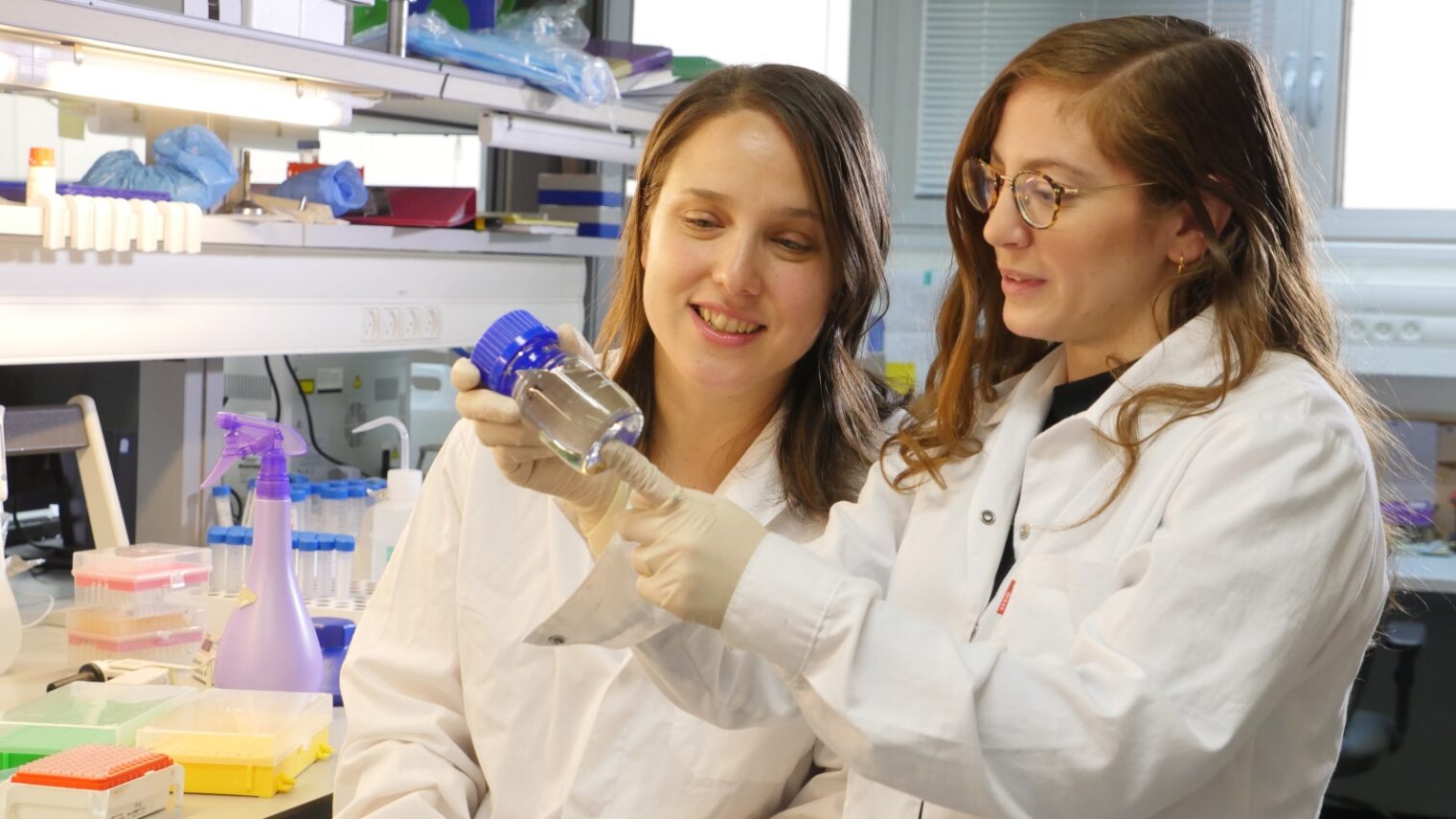

The results were published in the journal Nature Communications by Rolls along with doctoral students Tamar Ben-Shaanan and Maya Schiller, as well as Hilla Azulay-Debby, Ben Korin, Nadia Boshnak, Tamar Koren, Maria Krot, Jivan Shakya and Michal A. Rahat, and Technion Asst. Prof. Fahed Hakim, medical director of the Scottish EMMS Hospital in Nazareth.

According to Hakim, “Understanding the brain’s influence on the immune system and its ability to fight cancer will enable us to use this mechanism in medical treatments. Different people react differently, and we’ll be able to take advantage of this tremendous potential for healing only if we gain a thorough understanding of the mechanisms.”

The authors emphasized that the study is preclinical and that they tested only two cancer models (melanoma and lung cancer) and only two developmental aspects – tumor volume and weight.

However, this breakthrough may allow doctors to realize the physiological role the patients’ mental state plays in the development of malignant diseases. By artificially activating different parts of the brain, in the future it might be possible to encourage the immune system to block development of cancerous tumors more effectively.

Rolls explained that although the immune system has been proven able to fight cancer effectively if given the right tools, “the immune cells’ involvement in cancerous processes is a double-edged sword, because certain components in these cells support tumor growth. This is done by blocking the immune response and creating an environment that is beneficial to growth.”

Rolls has been studying the brain’s effect on the immune system for several years. In a study she published in 2016 in Nature Medicine, she showed how the immune system can be stimulated to work more effectively by manipulating the brain’s reward system – which operates in positive emotional states and in anticipation of the positive.

The main breakthrough in the present study is the dramatic contraction of cancerous tumors in response to the activation of the brain’s reward system.

Rolls cautioned, however, that the findings are not necessarily applicable to all types of cancer and that the experiments have not been done on humans at this point.

The artificial manipulation that worked on mice “most probably works differently” in humans, she said, “especially because other systems are also involved. For example, stress may counteract these reward system effects.”

Rolls said it’s not as simple as thinking positively to get better. “People are very different in their reactions, and until we fully understand how this works, it merely offers a potential.”

The study was supported by the Adelis Brain Research Award, a $100,000 research grant won by Rolls in June 2017. The prize is intended to encourage excellence in the field of brain research in Israel and to translate the research into global impact for the benefit of all humanity.