For the first time ever, nearly 200 of the rarest biblical manuscripts and texts are displayed at the Bible Lands Museum in Jerusalem, through October 2014.

“The Book of Books” exhibition includes original fragments from the Septuagint, the Vulgate, the Gutenberg Bible and the Cairo genizah, along with medieval illuminated manuscripts, Torah scrolls and other biblical relics. At the end is a working replica of the 15th century Gutenberg printing press that revolutionized the availability of the Scriptures.

“The exhibition is about the Bible as a book, not about theology,” says curator Dr. Filip Vukosavović as he takes ISRAEL21c through the show. “We cover over 2,000 years of the existence of the Bible as a physical item, and how it developed chronologically, geographically and linguistically throughout the world from Israel, where both the Hebrew Bible and New Testament originated.”

Since opening in October, the show has drawn so many visitors that its six-month run was extended.

One reason for its popularity is that “Book of Books” is not just artifacts displayed under glass. Using iPads installed throughout the exhibition, viewers can “open” the priceless works, magnify and browse through images of all the pages, and click on bullet points to learn additional information. Audio-guides are available in Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, Hebrew, English, Arabic, Russian, German and Dutch.

Vukosavović shows ISRAEL21c how infrared light technology lets visitors discover, via the iPad, hidden layers of erased text on the pages of the Codex Climaci Rescriptus. Some of the scriptures inscribed in the sixth century in Greek and Christian Aramaic were “repurposed” by ninth-century Syriac scribes for a translation of Greek texts by John Climacus, a seventh-century abbot.

Every item in “The Book of Books” is original aside from facsimiles of Dead Sea Scrolls fragments and the 11th-century Khabouris Codex.

Earliest biblical evidence

The exhibition grew out of the Green Collection, some 40,000 biblical antiquities accumulated in the past four years by the Green family of Oklahoma. The Greens, who are Christian, plan to install the items in a future Museum of the Bible in Washington, DC. For now, a traveling exhibit is crisscrossing the world, with Jerusalem and the Vatican two significant stops.

According to Bible Lands Museum Director Amanda Weiss, “The Book of Books” took nearly two years of work by scholars in Jerusalem and Oklahoma City, “with the vision of creating a broad exhibition on the development of the Bible, its canonization and dissemination through the centuries. Sensitivity to presenting an equally respectful representation of the Bible as the source for both Judaism and Christianity was a primary goal from the start.”

“They approached us because they wanted an exhibition in Israel,” says Vukosavović, a Montenegro native with a doctorate in Assyriology from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. “Despite the fact that we are the biblical land, there was never an exhibition of this type here before.”

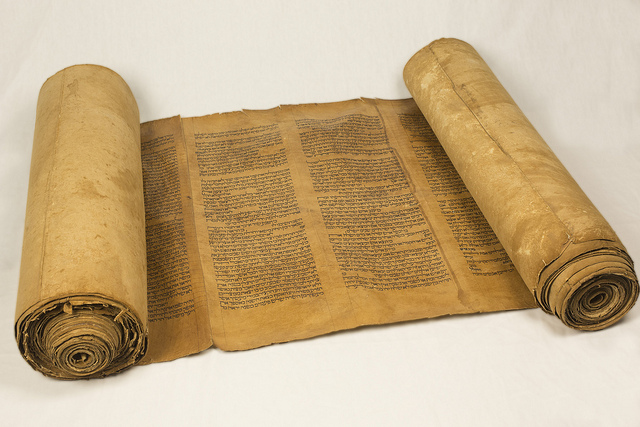

“The Book of Books” begins with items dating from the Second Temple period, from the third century BCE to the first century CE. “This is the era from which we have the earliest physical evidence of the Bible,” says Vukosavović. “We are not going into when it was written and by whom. That’s not the point of this exhibition.”

Papyrus pages of the Septuagint, from third to fourth century Egypt, bring to life the Talmudic legend that the first Greek translation of the Hebrew canon was ordered by King Ptolemy II and carried out by 70 or 72 Jewish sages who worked separately for 70 days yet produced exactly the same translation.

Vukosavović points out that while this is only a legend, “it shows the importance of translating the work into Greek, because by that time, up to one million Jews were living in exile in Egypt and did not know Hebrew.”

There may have been earlier translations into Aramaic, but the Septuagint became the Old Testament for Christians and is here displayed for the first time.

Also from Egypt are very early fragments of Christian Scriptures, including papyrus versions of the Gospels that weren’t canonized with the other four; and fragments of the 300,000 Jewish documents hidden away for 1,000 years in the Cairo Genizah.

The Bible moves through history

The floor of the exhibition is a map, taking visitors from Israel through the sands of Egypt, through the Middle East and on to Southern and Western Europe as the Bible spread across the world.

Ancient illuminated manuscripts from Armenia underline the fact that the Armenian Church was established in 301, 79 years before Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire. Vukosavović notes that churches from early Armenian, Syrian, Greek, Coptic and Ethiopian traditions exist to this day in Israel, mostly in the Old City of Jerusalem.

Two early copies of the Vulgate, from Italy and France, represent some of the first Latin versions of the entire biblical canon in one volume.

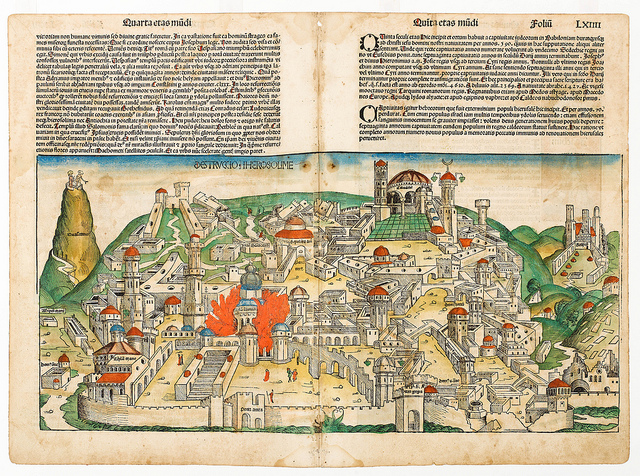

“Chronicle of Biblical History,” a five-meter-long, 14th century Latin treatise by an Italian friar and inquisitor, uses words and pictures to link Adam to Jesus, and lists kings, emperors and popes through 1346. The purpose of the unusual work, says Vukosavović, was to use the Bible to support or question the legitimacy of both secular and ecclesiastical rulers.

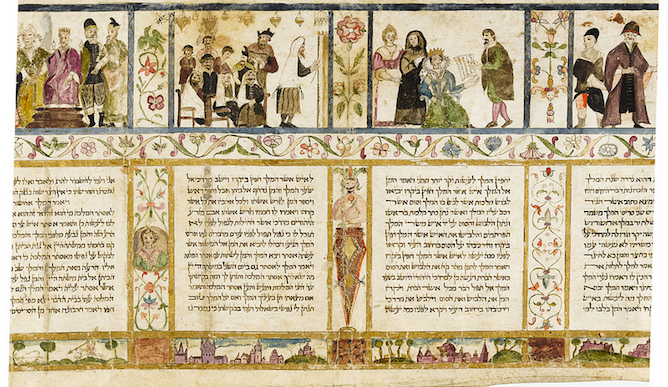

An Italian 17th century illuminated Scroll of Esther scroll employs comic-book-style illustrations that sometimes suggest commentary to the text. Vukosavović points out that the villain Haman is clothed as a Turk while everyone else is in current Elizabethan garb. At the time, the Ottoman Empire posed a serious threat to Europe, he explains.

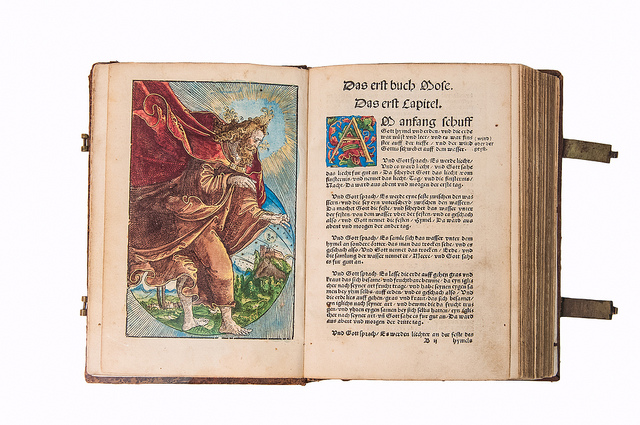

Martin Luther’s 16th century German translation and King James’ 17th century Old English translation are on display along with polyglot Bibles containing as many as nine languages on the same page so that scholars could compare translations.

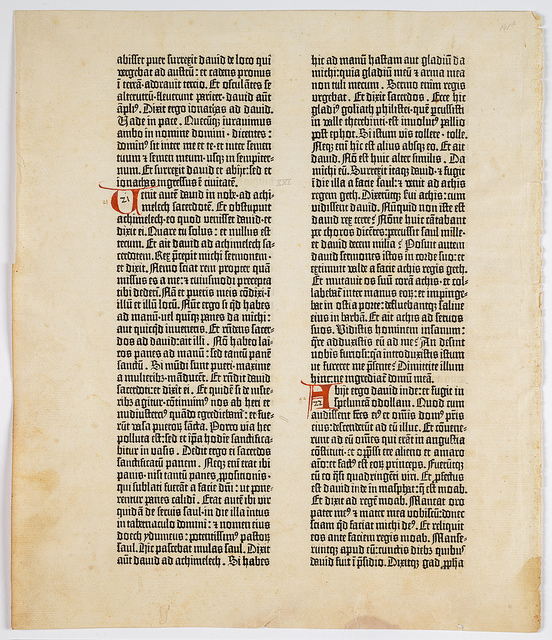

Two leaves of the 1450 Gutenberg Bible are also displayed. The Gutenberg Bible represents a turning point in biblical history.

“This is the real book of books,” says Vukosavović. “The Gutenberg Bible is the most expensive printed book in history. [German craftsman Johannes] Gutenberg printed about 180 copies, and only about 50 exist today.”

By the end of the 15th century, thousands of publishing houses in Europe were printing millions of Bibles. “Can you imagine the impact in terms of availability? You didn’t have to go to synagogue or church anymore to hear the Bible. You could read it at home,” says Vukosavović. “Gutenberg’s effect is immeasurable.”

Mass printing enabled the Bible to become the world’s best-selling and most widely distributed book. Guinness World Records estimates that some five billion copies have been printed since the 19th century, in 2,500 languages.

For more information on “The Book of Books,” see http://www.verbum-domini.com/?q=bookofbooks.