Oh Jerusalem! The city is holy to the three major monotheistic religions but lurking under the surface is another Jerusalem that harbors unholy mysteries, perhaps even ghosts.

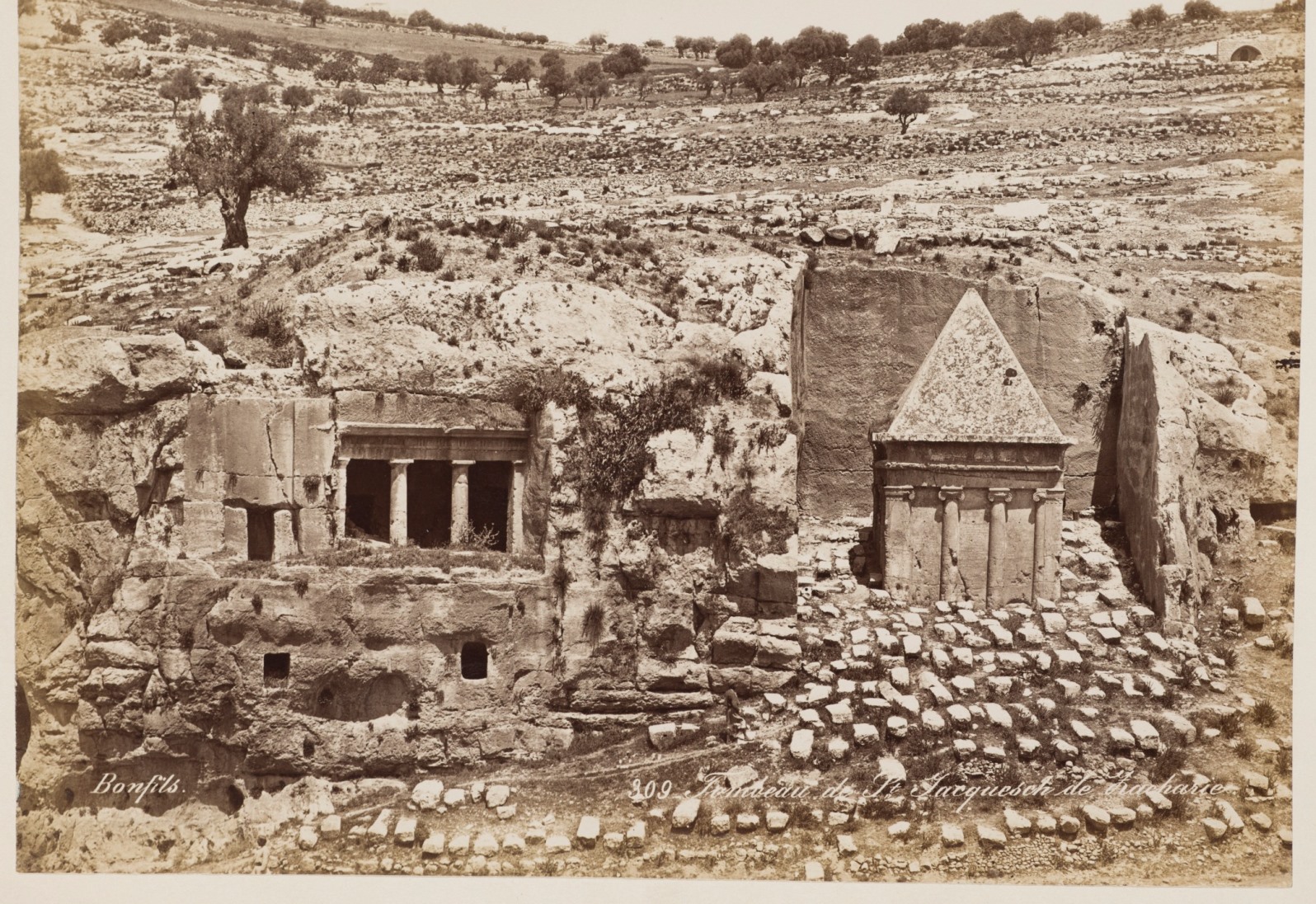

The dark underbelly of Jerusalem dates back to biblical times when the Valley of Hinnom outside the city walls was a place of pagan child sacrifice. Little wonder that the place, whose Hebrew name Gai ben Hinnom (transmuted to the Latinate “Gehenna”), became analogous to the concept of “hell” and was considered cursed.

The valley served as a necropolis for an ever-expanding number of cemeteries from the Judean Kingdom (7-8th century BCE) through the Byzantine period (4-7th centuries CE). A Crusader-era structure (12-13th century CE) has been identified as a burial place for Christian pilgrims who died in the Holy Land. Its nickname: “House of Bones.”

Perhaps because the Torah forbids communicating with the spirit world, Jerusalem’s spooky places are not so much haunted by spirits as they are subject to being cursed by humans. Nonetheless, Jerusalem has its stories of apparitions, mystics, dybbuks and their rabbinical expulsions.

Old-time Machane Yehuda residents swear that as late as the 1970s some neighbors peered through a window to witness an exorcism when a flame shot out of the toe of a young girl possessed by a demon. And that’s just one of the city’s ghostly legends…

Montefiore’s Carriage

British-Italian financier, banker, activist and philanthropist Sir Moses Montefiore made seven trips to Palestine between the years 1827 and 1875. In 1834, he rode in his own carriage to visit Jewish communities throughout Europe, Russia, the Ottoman Empire, Morocco and Palestine.

After Montefiore’s death, the carriage changed hands and was brought back to Jerusalem by Boris Schatz, founder of the Bezalel Academy of Art & Design, where it stood in the courtyard and eventually fell into disrepair. In 1963, the carriage was renovated and, in 1967, placed in the Windmill Plaza of Mishkenot Sha’ananim, the neighborhood Montefiore established in 1860 as the first settlement outside the Old City walls.

In his song “Sir Moses Montefiore’s Carriage,” songwriter Haim Hefer imagined Montefiore’s last years and recounted a bit of local Jerusalem lore:

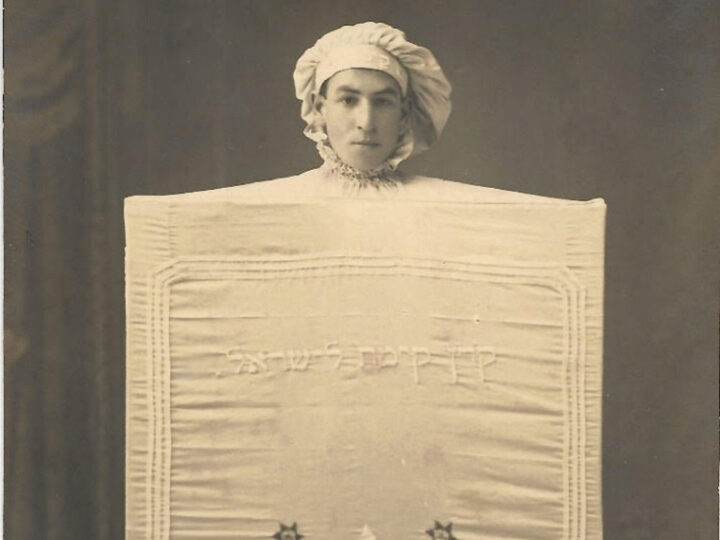

“Wrapped in a silk prayer shawl and resting in a casket / Sir Moshe ended his final journey / But there are those willing to swear that sometimes at night, surrounded by darkness / They’ve seen Montefiore next to the chariot / And he boards the carriage…”

The municipality restored the carriage and put it on permanent display next to the Montefiore Windmill in 1976. The carriage was destroyed by fire in 1986. At the initiative of the Jerusalem Foundation in 1990, the carriage was reconstructed using fragments that remained of the original and reinstalled in its glass case. Since then, there have been no more reports of ghostly sightings.

The Dead Groom’s House

From 1891 to 1917, the Municipal Hospital on Jaffa Road was the city’s central healthcare facility. But it stood empty for 10 years prior, reviled as “The Dead Groom’s House.” Bertha Spafford-Vester, daughter of the American Colony founders, told the tale in her memoir, My Jerusalem:

“It was being built, about the time we arrived [in 1881], as the future home of a couple about to be married. The young man was the only son of an Arab Roman-Catholic family who lived near our home in Haret-es-Sa’ad-ieh. Before the wedding took place, he died. …

“The mourners gathered in the room where the dead man was propped up in a chair and his lovely young bride was brought up to him, gorgeously decorated with jewels and flowers and wearing an elaborate brocade dress and the customary wedding veil. The ‘joy shout’ was raised by the mourners, or guests, and his mother danced before the couple with a lighted candle in each hand, the traditional dance the mother and relatives perform before a bridal pair.

“‘It is my duty to dance,’ she repeated, and the guests joined in, ‘Yes, it is your duty.’

“As she finished her dance she tore her clothes, gave the terrible death cry, and snatched the veil from the bride’s face. Then the corpse was laid in the coffin and the funeral ceremony held.

“Mother came home shaken by the spectacle. The violent demonstration of grief evidently killed the mother, for she died soon after. So, one more house stood unfinished for many years in Jerusalem.”

Since the British Mandate, the building has served as the Ministry of Health’s district office.

The Russian Hospital

One of the oldest districts outside the Old City walls, the Russian Compound was built between 1860 and 1890 to provide Russian Orthodox pilgrims with a mission, consulate, hostel and hospital that also housed a funeral home and morgue. The latter function may have been the reason for rumors that the place was haunted.

In 1948, the building was used for wounded Israeli troops and became known as AviHayil. Today, the building serves as municipal office space, but it took years for it to shed its ghoulish past.

In a 2010 article, Jerusalem-based reporter Omri Maniv wrote about his visit to the Russian Hospital building: “I go with Uziel, who works there, down the steep staircase to a stuffy basement. In the cellar, on the bookshelves stand black binders that appear to contain various and strange magic spells. As a whole, the place is reminiscent of a medieval library.

“Uziel claims that the priests are forbidden to enter the building, even for work. The terrifying isolation there gave rise to his decision to bring in a quorum of ten guys to perform a rending of garments [ceremony] for safety’s sake. We asked for forgiveness in all cases, just as is done before a funeral, when preparing the body, cleansing and honoring the dead person. When Jerusalem’s Municipal Square was being built, the workers objected to working in the accursed building because it was haunted. A rabbi was called in to solve the issue; he said, ‘The city of Jerusalem is sacred, let not your hearts be troubled’ and conducted prayers there.

“‘Security guards are afraid to do late-night patrols because they think there are ghosts here,’ says one worker. ‘There used to be people who didn’t want to work here because the building was cursed and had all sorts of diseases. There was one female security guard working here at night, and the alarm sensor went off. She went in but found nothing. Rumor has it that she left, vowing never to return.’”

Orient House

The magnificent East Jerusalem stone mansion known Orient House was built in 1897 as the residence of the al-Husseini family. Orient House has, in recent years, became synonymous with Palestinian nationalism, but the building’s infamous reputation began in 1898 with the visit of Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany to Jerusalem.

As the story goes, the al-Husseni family was preparing to receive the Kaiser and his wife, Augusta Victoria, when a tragedy occurred. Ruwaida, daughter of the Ottoman Minister of Education in Jerusalem, had been chosen to present the queen with a gift. While she helped the servants light the rooftop lanterns, the child’s gauzy white dress caught on fire and she burned to death. The official visit went on as planned, under the shadow of the horrific incident.

Over the years, the family continued to receive important guests, such as Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia after his exile in 1936. Between 1948–1950, the building was headquarters of the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). Two years later, the owners turned it into a luxury hotel but following the 1967 Six-Day War and the capture of East Jerusalem by Israel, the hotel closed and the building went neglected.

Starting in 1983 , Orient House served as the Palestine Liberation Organization’s de facto headquarters. Subject to periodic closures by the Israeli government, in 2001, following the Sbarro pizzeria bombing, Israel closed the Orient House; it remains shuttered to this day.

The Enchanted Road

During more peaceful times, for many years the road running downhill through the Arab neighborhood of Jabel Mukaber was a destination for curious visitors who drove to a particular spot, put their cars into neutral, released the brakes, and then squealed in delight as their vehicles appeared to roll uphill against gravity.

The road, known locally as the “magic” or “enchanted road,” is among several of Israel’s “gravity hills” — places where surrounding landscape produces an optical illusion.

The Cursed Building of Agrippas Street

The most famous of Jerusalem’s “cursed” buildings is Eini House at 111 Agrippas Street. It’s well-known throughout the city that any business opening there will fail, doomed by a curse placed five decades ago by Rabbi Shalom Sharabi, head of a kabbalist house of study.

Legend has it that Sharabi was angered when the building, then under construction, rose to the height where it blocked out the rising sun, thus preventing him from saying his morning prayers on time. When the contractor, one Meir Eini, refused to accommodate Sharabi’s (somewhat unreasonable) demand to cease construction, he and his building fell victim to a curse.

From the outset, turnover was high. Office spaces went unrented. Apartment units did not sell. One after another, businesses that opened in Eini House lost money, went bankrupt or were forced to close – including the headquarters of the far-right Kach Party, which was removed from the building by court order.

Other buildings on the street are said to have been affected by the ricocheting curse: the failed Shukanyon covered market at 88 Agrippas and another white elephant, the Clal Center at the corner of Agrippas and Kiah streets.

Of course, there may be simpler explanations for these unsuccessful ventures – bad business decisions and bad locations, for instance.

But in a city where talismans and amulets to ward off the evil eye are sold at every kiosk, where everyone just happens to know someone who reads coffee grounds, tarot cards or horoscopes, and even the supermarket checkout guy has a second gig as a giver of blessings, well, there just may be some other-worldly forces at work in Jerusalem.

This article was first published on October 30, 2019.