Israel will segue from “startup nation” to “self-manufacturing nation” if leaders of the non-profit Reut Institute realize their ambitious dream.

“Our vision is for Israel to lead the coming revolution of self-manufacturing,” says Roy Keidar, CEO of the Reut Institute, a Tel Aviv-based policy group established in 2004 “to make an indelibly Israeli and Jewish contribution to the future of humanity.”

Spread the Word

• Email this article to friends or colleagues

• Share this article on Facebook or Twitter

• Write about and link to this article on your blog

• Local relevancy? Send this article to your local press

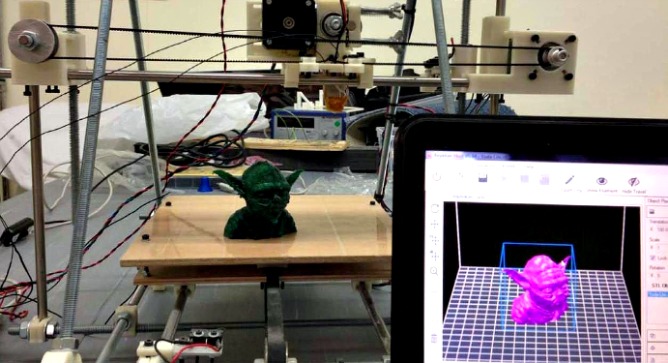

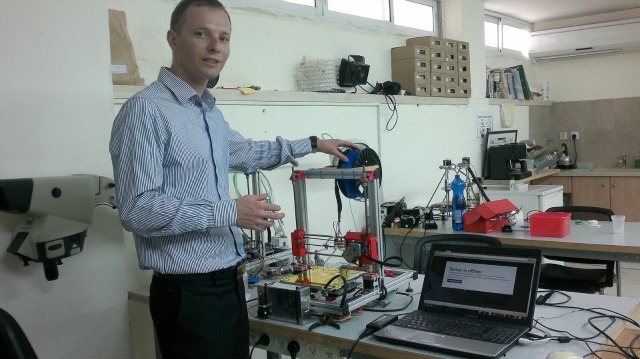

That future will see folks of all ages making their own products with inexpensive materials and open-source technologies, Keidar explains to ISRAEL21c at Reut’s first Communal Technological Space (CTS) 3D printing lab, soon to be replicated across Israel as part of Reut’s XLN (Cross-Lab Network) Initiative.

“We have such sophisticated easy-to-use tools, like 3D printers, that today it’s not a dream that you can wake up in the morning, sketch an invention, put it on your computer and then print it,” says Keidar. “I have done it myself.”

Three-dimensional printing has been making international headlines for the beneficial objects it can generate (a robotic exoskeleton, haute couture fashion) and also for its darker side (plastic handguns).

“Every technology that you can use for bad can be used for good,” Keidar points out. A knife to cut cucumbers can also be a lethal weapon, after all.

Reut’s aim is to educate ordinary Israelis to take ownership of this advancement for the benefit of humankind.

Design contest for special needs

US President Barack Obama recently announced plans to open a network of 15 self-manufacturing sites in the United States as a way of revolutionizing the economy.

“Well, Reut has been deploying a remarkably similar vision, named XLN, designed to place Israel at the leadership of this coming revolution of self-manufacturing,” Reut founder Gidi Grinstein tells ISRAEL21c.

“We have to create broad technological literacy in this area, to groom leadership and to focus this revolution, and to do it in a way that is inclusive.”

One of the first XLN projects challenged students at the Tel Aviv CTS to self-manufacture inexpensive helpful devices for people with special needs, using things like rubber bands and plastic. Milbat, an Israeli non-profit that facilitates integration of disabled and elderly people through adaptive technology, acted as consultant for the competition.

Five finalists will be judged on August 29: Industrial design student Gilad Agam’s plastic earpiece that routes sound from a phone directly to the inner ear; a rigid wrist grip for walkers by occupational therapists Orit Nahmani Asher and Yuval Naveh; a casting kit for custom-designing tableware for people with restricted hand mobility, by engineer Moshe Borocin; teenager Aya Efron’s customizable eyeglass frames for children; and an ergonomic computer-mouse add-on by industrial design student Eran Zrihan.

Production by the masses

The possibilities for self-manufacturing are infinite. All that is needed is access to the knowhow and materials.

“Barriers between producers and consumers are being broken,” says Keidar. “For the last 200 years, production was being done somewhere else and now we can do it ourselves. This is a huge economic revolution from mass production to production by the masses.”

Hardware for this field is available as never before, especially after the 2012 merger of US-based Stratasys and Israel-based Objet, two global leaders in commercial 3D printing, which then acquired desktop 3D printing company MakerBot in June 2013.

The Israeli startup Something3D is working to democratize the trend by offering an inexpensive 3D printer for home use, plus step-by-step directions for making items suggested by its community of users.

However, says Keidar: “XLN is not about making a printer but making sure we’re at the forefront of the self-manufacturing revolution. We are opening physical spaces that can serve as a place to educate the Israeli public and develop the kind of leadership that evolves to startups and companies.”

The Tel Aviv CTS, launched in June and offering two classes per week, houses a happy jumble of extruders, laser cutters, CNC routers, PCB carving tools and homemade 3D printers. Machines made of open-source components are better understood by those using them, Keidar points out. “They can change or enhance the equipment according to need.”

A global meeting point for problem solving

The XLN Initiative has opened a new CTS in Haifa, and similar labs are planned at Bat Yam’s Design Terminal and in Kiryat Shmona, Shlomi, Jerusalem, Eilat and Safed (Tzfat). The goal is to have about 40 local and regional centers across Israel, prioritizing poorer periphery areas.

“Each space is pretty much independent and will bring its unique added value, but they are all interconnected,” says Keidar. “Crossover is so important to us because it’s a meeting point to share ideas and create peoplehood.”

Someone in Jerusalem or Eilat will thus be able to collaborate on a project with someone in Kiryat Shmona or Shlomi. Reut’s long-range vision is to expand the project to Jewish communities outside Israel as well.

“The language of technology is universal,” says Keidar. “It can narrow gaps between Jews in Israel and overseas, and provide a meeting point between communities of need and communities of knowledge. Together, they can come up with innovations when someone has a specific need but doesn’t know how to solve it.”

Partnerships with municipalities, corporations and funders — such as the UJA Federation of Greater Toronto, which is sponsoring two CTS labs — keep the operating budget within reach. Eventually, the program is meant to be self-sustaining by introducing fees and revenue-generating labs.

Keidar calls the XLN Initiative “an energy boost for societal innovation. Israelis are so creative, they will take the idea and run.”