When I first moved to Israel from the UK in the early 1990s, Christmas was a difficult time of year for me.

Israel may be the birthplace of Christianity, but you’d never have guessed it. In the 1990s, this was a land without Christmas. No carols, no trees, no celebrations of any kind, and definitely no corny Christmas movies on TV, or songs about reindeer playing in every shop.

While I’m not a religious Christian, the holiday of Christmas was a central part of my year and I missed it terribly.

What made it worse was the knowledge that I was “other.” In a land primarily of Jews and Muslims, I felt I didn’t belong. It’s hard in any society to be different, but in those days Israel was still a nation of strict conformity and you had to fit in. I most certainly didn’t and it was a lonely experience.

So as Christmas approached each year, I headed straight back to England, often with my Jewish husband, heading joyfully back to all those symbols of the holiday that everyone else in the UK loves to complain about.

As I started to have children, the trip got harder. Then came one year that I couldn’t go. We had two small children by then, and the thought of making Christmas for them here, alone, without any kind of support, was a daunting prospect.

I phoned my mum.

“It’s the mother who makes Christmas,” she told me. “It’s not the kindergarten teachers, or the school, or all that razzmatazz in the stores or on TV.”

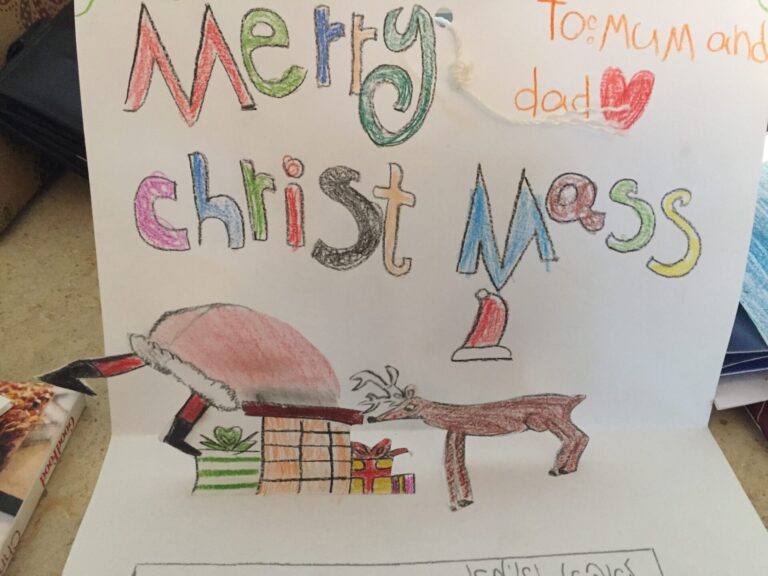

I took her at her word. As December progressed I started making Christmas decorations with the children. We made cards and lanterns and snowman-shaped cookies. I found an old tape of Christmas songs and played it repeatedly.

My husband and I found a Christmas tree and decorations in Jaffa, and on the day itself we took a day off and celebrated with stockings and presents and whatever Yuletide food I could make.

It felt strange at first, but the children embraced it with passion and a tradition began.

As my confidence grew, I started making more and more of the traditional English Christmas dishes – searching for ingredients in Israel or bringing them from England in the months beforehand, much to the bemusement of the Israeli security guards at Heathrow, who would search my suitcase and discover black treacle, marzipan, royal icing, and mixed spice.

Mince pies, brandy butter, stuffing, bread sauce, I started to master it all, even the rich brandy-laden Christmas cake that has to be prepared weeks in advance and which my Israeli friends call “old cake,” as in “You made that cake two months ago!”

In the years since then a transformation has taken place in Israel. Though still vastly outnumbered, I no longer feel quite so alone. You can buy Christmas trees in Toys R Us. Christmas decorations are on sale in the malls. The supermarket chains sell chocolate Santa Claus candy and stockings stuffed with sweets.

There are also Christmas celebrations in Jaffa, Jerusalem, Haifa and Nazareth and people of all faiths come out to enjoy Christmas events around the country.

The change is mostly due to the massive Russian immigration of the 1990s, when more than one million Russians and Eastern Europeans flocked to Israel, boosting the country’s population by 20 percent in just a few years. Many – like my children — have mixed heritage. A small percentage are registered as Christian, but around 270,000 are not Jewish according to Jewish law.

After decades of communism, many do not celebrate either Christian or Jewish holidays. Instead they celebrate Novigod on January 31st and use all the symbols of Christmas, the trees, presents and Santa Claus – reincarnated as the grandfather of ice — to celebrate.

I’m not going to pretend it’s always easy. Not everyone in Israel is open or welcoming, and there are always some who complain about public displays of Christian symbols – including a colleague at a different newspaper who told me that she hoped I kept my curtains shut so no-one could see my Christmas tree.

There are also those who have something negative to say about mixed marriages, but in my world in Israel, these people are a tiny minority

My Jewish husband, his family, our friends and neighbors embrace our celebrations, and embrace our differences.

Many years Hanukkah coincides with Christmas so we often hold a Hanukkah-Christmas party for friends and neighbors where we light candles, eat sufganiyot and “old cake,” singing Hanukkah songs next to the Christmas tree.

Our boys, three of them now, aged 16, 21, and 25, identify as Jewish, even though in the complicated way of things in Israel they are not, but they celebrate Christmas as enthusiastically as they do the Jewish holidays.

Is that a problem for them? Is it confusing? Once I picked up an exercise book of one of my kids when they were still young and found that he had described himself as a “little bit Christian.”

I used to worry about it, but I don’t anymore. Years ago I interviewed a young Palestinian who had teamed up with an Israeli to try to race formula cars in Britain. His mother was Christian and his father Muslim.

“And how is that?” I asked, thinking of my own boys.

“I’ve been brought up to have two religions,” he said. “We celebrate both Muslim and Christian holidays. I think it’s the best. It makes you far more open-minded.”

I look at my own boys and see how they traverse their Jewish and Christian roots, and I’m proud of them.

Christmas comes next week, and we will celebrate as we always do here. We all take the day off from work or school, and have a small, intimate family day with stockings, a walk on the beach, back home for Christmas lunch with all the traditional foods and of course that quintessential part of an English celebration – Christmas crackers.

Our Christmas in Israel is a modest affair, free of the overblown consumerism that affects the US and Britain. It’s a family day, a day out of step with the rest of society here, and that somehow makes it even more unique and special. While everyone else is going about their daily lives, we are enjoying a quiet day together.

Girlfriends are joining the celebrations now and that’s even more wonderful.

Somehow our Christmas, here in the land where this holiday is really not supposed to happen, is actually closer to what I always hoped Christmas would be.