Israeli chemist Yifat Miller and her PhD student Yoav Atsmon-Raz have found a critical link between Type 2 diabetes (T2D) and Parkinson’s disease (PD).

Miller’s research at Ben-Gurion University (BGU) of the Negev in Beersheva revealed, for the first time, the atomic structure of a brain protein fragment called non-amyloid beta component (NAC), known to trigger PD when it clumps together.

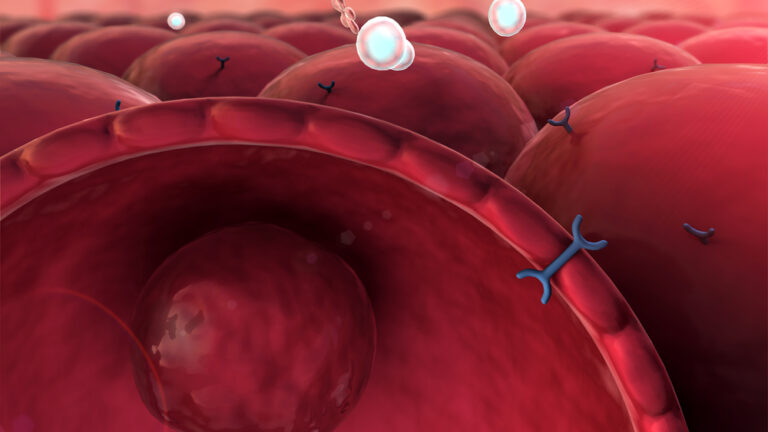

The same clumping action by an endocrine hormone called amylin harms insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas, leading to T2D. Amylin is also found in the brain, and previous studies show that its clumping there, with the aid of the peptide amyloid beta, is related to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and the death of neurons.

Miller suspected that this mechanism explains why people with T2D face twice the normal risk of developing AD later in life.

“It was known that this aggregation causes the death of neurons, but no one knows how amylin and amyloid beta aggregate at the atomic level,” says Miller, who last year did a presentation with her graduate student Michal Baram at the annual American Biophysical Society on the interactions between amylin and amyloid beta at the atomic level.

“Our findings led us to the hypothesis that if amylin is located in the brain it can also interact with other proteins and peptides in the brain,” she tells ISRAEL21c.

One of these proteins is alpha-synuclein, whose fragment NAC is toxic to neurons and thus leads to PD. Miller and Atsmon-Raz decided to map the atomic structure of NAC to study how it aggregates, revealing for the first time the mechanism behind the clumping that causes PD.

With these findings, she strongly suspected she was closing in on a groundbreaking key to understanding of the mechanism that underlies T2D and neurodegenerative diseases.

T2D increases risk of Parkinson’s

Miller’s second goal was to shed more light on Parkinson’s and other neurodegenerative diseases, as well as the reason why people with type 2 diabetes have a higher risk for developing PD and not only AD.

Miller’s hypothesis was that amylin can also interact with NAC or alpha-synuclein.

“We propose that NAC and amylin aggregate together and kill neuron cells, and these aggregates lead to PD. So, we focused on understanding how amylin and NAC interact to form these aggregates at the atomic resolution.

“When we looked at their interactions as aggregates, we found an incredible synergy. It’s amazing how each one of these peptides induces aggregates in the other,” says Miller, whose grandfather had diabetes and developed PD toward the end of his life. “This is really important and novel, with broad interest.”

This study spanned nearly three years of research using sophisticated computer simulations. The findings were then confirmed through experiments.

“We based our predictions on already published experimental studies, but we are the first to publish the NAC structure of the aggregates,” explains Miller.

PD drug on the horizon?

Miller set up her lab in BGU in 2011 after three years of post-doctoral research on AD at the National Institutes of Health in Maryland.

With her staff of four graduate students and one post-doctoral researcher, she focuses on the link between type 2 diabetes and neurodegenerative diseases.

“Not many scientists in the world are studying this topic, and therefore there is a lot of work to do,” she says, noting that the research is funded by the European Union Seventh Framework Programme.

“Publishing our results will allow other scientists to use this information to learn more about Parkinson’s, its mechanisms and possible drugs to reduce aggregation. Now one could develop a drug to prevent this interaction so the risk of diabetes will not lead to the risk of Parkinson’s.”

Miller’s lab may continue investigating this further.

“Our work provides a lot of information for new studies to understand the mechanism of PD,” she says. “Perhaps the problem of regulating insulin contributes to PD. We have some ideas of developing a drug to prevent the interactions between peptides.”