At age 14, “Nathan” was living on the streets of his Israeli working-class town. Academically crippled by ADHD, he eventually attended a therapeutic boarding school and served in the army.

His employment future looked bleak until he heard about a Google certification program in digital marketing run by JDC-Tevet, a partnership with the Israeli government for the advancement and inclusion into the Israeli workforce of vulnerable populations — Arab-Israelis, ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) Jews, women, people with disabilities, Ethiopian immigrants, workers over 45, and other disadvantaged citizens like Nathan.

Now 22, Nathan is employed as a digital marketing manager and has lectured at his former boarding school to inspire other students.

JDC-Tevet is one of many private and public initiatives training underemployed populations to address a shortage of skilled workers for Israel’s burgeoning high-tech arena.

The problem is so acute that several companies recently launched BETA (Be In Tel Aviv), an alliance offering attractive relocation packages for overseas tech professionals.

But many experts believe the gap can and should be filled domestically.

“There’s a shortage of 10,000 high-tech workers in Israel today, and the answer is right under our nose,” says Stuart Hershkowitz, vice president of Jerusalem College of Technology (JCT), which runs special programs preparing Haredi (ultra-Orthodox) and Ethiopian Israelis for high-tech careers.

These populations suffer from a lack of STEM (science, technology, engineering and math), English and higher-education opportunities. Only the brightest and most motivated can successfully catch up to their peers via an intensive one-year preparatory program.

Yet JCT currently has 553 Haredi women and 402 Haredi men studying computer science and engineering (plus hundreds more studying professions such as nursing and business), on separate campuses. Israel’s Council for Higher Education found that two-thirds of the 1,000 Haredi computer science students in 2017 were at JCT.

On average, high-tech wages are 50 percent higher than in other Israeli professions.

“Of all the Israelis in high-tech earning 17,000 shekels and above [per month], 0.3 percent are Haredi men and 0.4 percent are Haredi women. That means they’re not part of the startup nation and that has to change,” Hershkowitz tells ISRAEL21c.

In a few years, he predicts, “a very large percentage of Orthodox women will be computer engineers.”

In 2013, two students in the Haredi men’s track founded the WishTrip travelers’ app. JCT houses the startup, which now employs 25 graduates.

“There’s a shortage of 10,000 high-tech workers in Israel today, and the answer is right under our nose.” — Stuart Hershkowitz, Jerusalem College of Technology

The business partners came to JCT from full-time Talmudic studies in their late 20s because they wanted to better provide for their growing families even though it meant learning English and math from scratch.

“We are so very grateful to Stuart and JCT for giving us this opportunity,” cofounder Bezalel Lenzizky tells ISRAEL21c – in English.

Among other Israeli programs integrating the ultra-Orthodox into high-tech are KamaTech, which supports startup entrepreneurs; and Temech for Haredi women.

High-tech for Arab-Israelis

According to a 2017 Israeli Innovation Authority report, approximately 270,000 Israelis work in high-tech. Arab-Israelis comprise just 3% of that sector. A variety of governmental, philanthropic, corporate and academic programs aim to raise that number to 20%, reflecting their proportion in the general population.

Hebrew proficiency is one hurdle in reaching this goal, says Prof. Bertold Fridlender, president of Hadassah Academic College in Jerusalem, which offers pre-academic programs for Arab, Haredi and other disadvantaged students.

Next year HAC will implement a mandatory Hebrew class as part of the first-year studies for Arab students who don’t need an extra year of pre-academic Hebrew, enabling them to graduate faster.

Software developer Musmar Walaa was one of many students from Nazareth to study computer science at HAC on a full scholarship. He says he struggled the first year to get his Hebrew up to par, but now he communicates easily with coworkers – first at Intel and now at NICE Actimize.

Muhammad Massalha, 24, also earned a degree in computer science at HAC. He did full-stack software development at HP for 18 months and now works at a four-person startup in Caesarea. “I am part of the team and a stakeholder, too,” he tells ISRAEL21c.

It wasn’t easy getting that first job, he says, not because of prejudice (“Big companies don’t look at Arabs and Jews, just at grades and expertise”) but because Arab-Israelis generally don’t serve in the army and therefore lack the work experience and social network that many Israeli soldiers gain by serving in technological units. So Massalha did a lot of networking at high-tech hubs in Jerusalem.

“You need to go the extra mile,” he says. “I had a lot of friends in the high-tech community and they helped me send around my CV.”

Fridlender says the percentage of HAC graduates working in their field of study actually is the same (85%) for Jews and Arabs. Arabs comprise about 19% of the 4,000-student population.

“Our Career Center helps all our students find jobs and we have an Arab-speaking adviser, an alumna of our college, working there to help close the cultural gap for job-seekers,” Fridlender tells ISRAEL21c.

Nonprofit organizations such as Tsofen also work with the Israeli government to integrate more Arabs into the high-tech sector, mainly in the North. Sadel Technology is providing high-tech jobs to Bedouin Arabs in the South.

Ethiopian-Israelis

Several Israeli institutions of higher learning, including HAC, JCT and Ono Academic College,for example, offer subsidized pre-academic and academic programs for Ethiopian-Israelis, many of whom come from low-income families.

Specifically focusing on preparing them for high-tech jobs is the non-governmental organization Tech-Career.

Established in 2002 — when there were only four Ethiopian-Israelis working in the high-tech field – Tech-Career now boasts hundreds of graduates and plans to build a new headquarters in Lod.

Director Takele Mekonen reports that less than four months after the completion of Tech-Career’s latest courses in Web and Java full-stack development, graduates received job offers from Oracle, AT&T, Intel, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Briefcam, Smarti and Checkmark.

“Two graduates have just signed contracts at Orbotech and Bynet. IBM, a company that has long provided guidance and mentorship, has hired its first Tech-Career graduate,” Mekonen said.

Tech-Career continually adds courses on skills demanded in the market, including Android applications, data security and quality assurance. A new software development course is planned in partnership with the Israel Innovation Authority.

Upskilling

Sigal Shelach, CEO of JDC-Tevet and deputy director of JDC Israel, says the partnership is piloting a new program in cooperation with the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, retraining and upskilling 45- to 75-year-old engineers from the high-tech industry to fill freelance positions in domestic and overseas companies.

“People of this age find it difficult to get into new fields or continue working past forced retirement,” says Shelach. “These are talented, experienced people who only need to refresh their skills.”

Infinity Labs R&D, another program retraining high-tech workers, was launched by Matrix, Israel’s largest software house, in 2014. Infinity has graduated about 450 people and currently has 150 students at its Ramat Gan and Haifa locations.

About two-thirds of Infinity’s students hold college degrees in STEM subjects but aren’t qualified for more than entry-level high-tech positions. The rest come from unrelated fields — rabbi, veterinarian, lawyer and farmer, for instance.

“We’re now looking at a few great people with no higher degree whatsoever, including minority and periphery populations,” Infinity co-CEO and founder Steven Harari tells ISRAEL21c.“No matter what they learned previously, we train them to be excellent developers capable of adapting quickly to new technologies.”

Infinity’s intensive seven-month program provides 1,800 to 2,000 hours of mentor-led training equaling more than two years of work experience, says Harari.

“Customers visit us two months before students finish training, find the person they want and tell us what they’ll need to know on the job.”

Participants receive a small stipend during the program and then become Infinity employees at one of 120-plus partner corporations doing jobs normally requiring a computer-science degree and several years of experience. After two years they may be employed directly.

The Labor and Social Services Ministry recently launched We Code, a free eight-month training and job placement program in programming and computer science for Arab-Israelis, Ethiopians, people with disabilities, Haredim and other marginalized populations between the ages of 25 and 30 in collaboration with JDC-Tevet and the private college IDC Herzliya (IDC). Graduates who integrate into high-tech for a year will be entitled to continue on for an undergraduate degree at IDC.

Israelis with disabilities

Israel also has programs that prepare citizens with disabilities to fill high-tech positions.

The SHEKEL organization for inclusion of people with disabilities runs employment programs for high-functioning people on the autism spectrum.

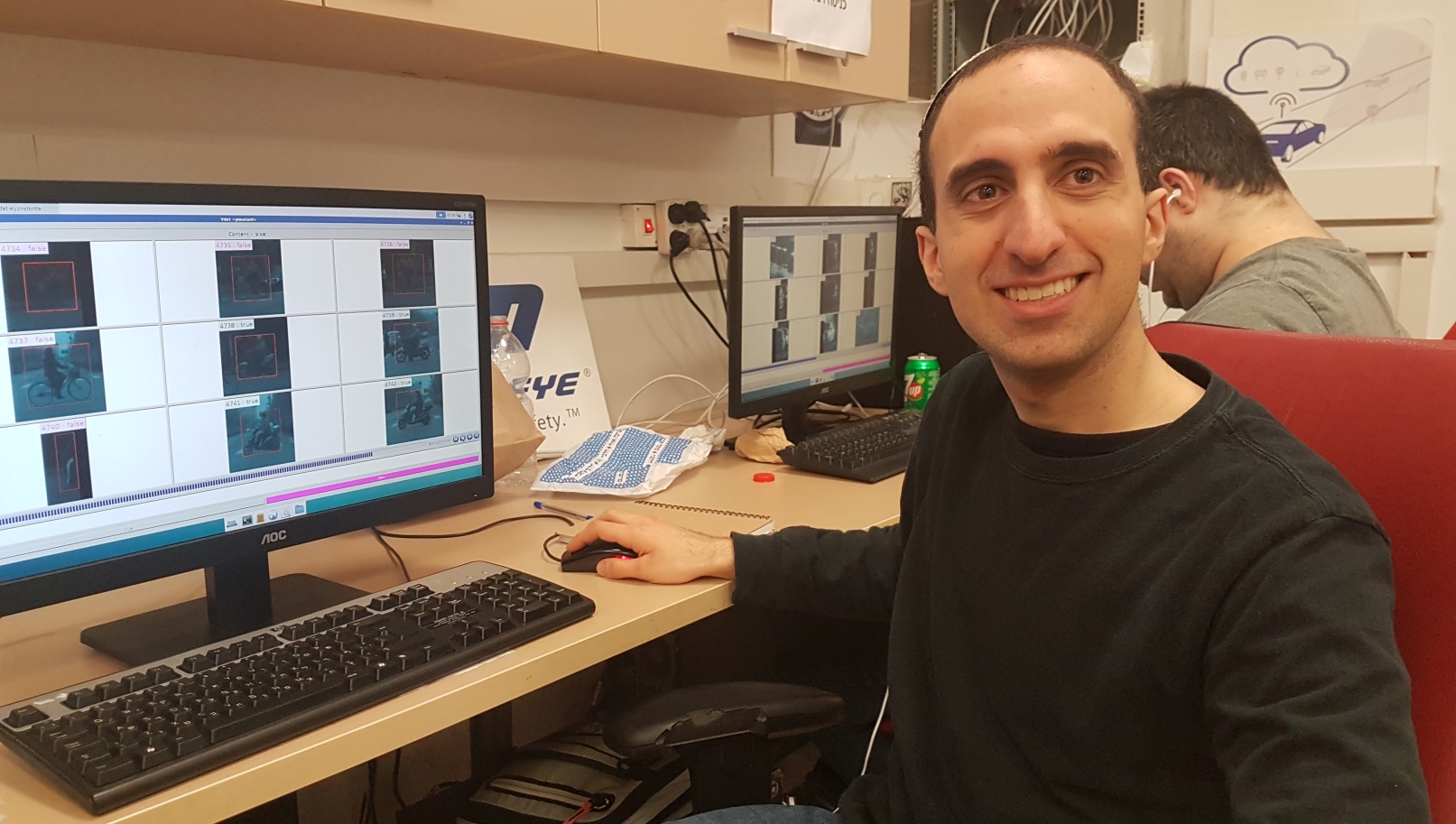

One of these programs teaches individuals with keen visual perception how to analyze video clips from roads across the world for Mobileye, the Jerusalem-based computer-vision giant that makes driver-assistance systems.

This groundbreaking partnership, begun two years ago, marks the first employment program for people on the autism spectrum in Israel’s corporate high-tech sector. Graduates of the eight-month course become full-fledged Mobileye employees.

Jonathan Trauner, 24, is in the current training cohort.

“I can’t tell you how terrific it is to be part of this project. It has taught me to be proficient and dedicated through effort,” he tells ISRAEL21c. “I enjoy the work immensely; it is so rewarding. You can grow up with adversity, such as Asperger, and use it to be the best you can be.”

Avi Hershkovitz, Mobileye QA team leader, says the project was developed at first in order to help the community and eventually became an inseparable part of Mobileye.

“We have reached a situation in which the SHEKEL team helps us a lot in the daily work and manages to improve the performance of the system,” he tells ISRAEL21c.

“We have already decided to keep growing and hiring more people to the SHEKEL team not only because we are satisfied with the team’s work and the cooperation with SHEKEL, but also because it is important for us to build a large enough team in order to meet with the broader demands and needs of Mobileye in its race for the autonomous vehicle.”