For cancer patients undergoing treatment, the ups and downs can feel like living through one of those B-level movies where the zombies just never seem to die: Victories of remission can quickly end in disappointment as the cancer returns once more.

Why this happens has long puzzled scientists around the globe, but a new multi-center team in Israel whittles the problem down to the roots of where cancer begins.

Spread the Word

• Email this article to friends or colleagues

• Share this article on Facebook or Twitter

• Write about and link to this article on your blog

• Local relevancy? Send this article to your local press

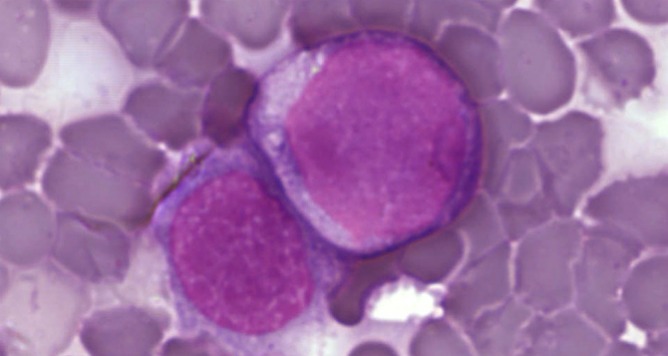

The Israeli researchers built a unique “family tree” of leukemia cells from living cancer patients to understand more about how cancer cells divide, spread and can outlast chemotherapy treatments.

This world’s-first will likely have profound implications for the way leukemia and other cancers are treated in the future, the researchers expect.

In the medical journal Blood, Israeli researchers — including Noa Chapal-Ilani, Prof. Ehud Shapiro and Dr. Rivka Adar from the Weizmann Institute of Science and Dr. Liran Shlush from the Technion-Israeli Institute of Technology — explain that tracing cancer stem cells back to where they began sheds light on how cancer reappears.

Until now there have been two main theories about why some cancers return after treatment. The Israeli study results may just put this debate to bed.

One theory is that chemotherapy can’t kill each and every cancer cell. The few cancer cells left behind eventually divide out of control again, leading to a relapse. The other theory is that while chemotherapy may be good at killing run-of-the-mill cancer cells that divide rapidly, it fails to vanquish slow-dividing cancer stem cells. This second theory was supported by the evidence.

It’s all in the family tree

Investigating the genetics of leukemia cells with the aid of computational biology, the researchers came to a new conclusion: “We know that in many cases, chemotherapy alone is not able to cure leukemia. Our results suggest that to completely eliminate it, we must look for a treatment that will not only eliminate the rapidly dividing cells, but also target the cancer stem cells that are resistant to conventional treatment,” said Shapiro.

Looking at how genetic information in leukemia cells is passed on as the cancer divides, they systematically reconstructed the cell lines – “family trees” of leukemia cells – from two patients to better understand how the cancer evolves.

One cell lineage was from a patient just after diagnosis. The other was from a patient who had undergone chemo and was suffering a relapse. The younger cells were shown at the tips of the branches, and the original or oldest cells at the base of the tree. Knowing that genetic material undergoes changes during cell divisions that get passed on to future generations of cells, the researchers were able to trace and compare mutations in order to pinpoint where the common ancestor, or the deadliest cancer stem cells, originated.

The leukemia-cell family tree demonstrated that cancer returns not from rapidly dividing cells that failed to be obliterated, but from slow-dividing cancer stem cells that are resistant to the typical kinds of chemotherapy that target rapidly dividing cells.

According to the researchers, this new finding can help lead to a new approach aimed at completely rooting out the cancer stem cells. Since chemotherapy most commonly targets only rapidly dividing cells, this would represent a paradigm shift in attacking cancer.