A unique material that gels with body heat –– already safely used in toothpaste, eardrops and medicine capsules –– is now the basis of a new product from Israel’s Theracoat to help cure bladder cancer and incontinence.

The substance formulated by Israeli scientists is known to the world of chemistry but was previously not used for treating conditions of the bladder, says Theracoat CEO Gil Hakim.

Some 15,000 people in the United States die every year from bladder cancer. About 73,000 new cases are diagnosed here every year, according to the American Cancer Society.

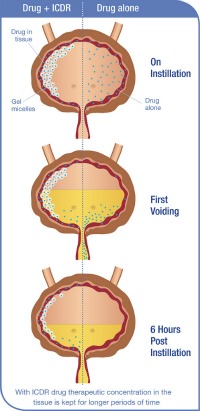

The substance in development by Theracoat takes novel chemistry from existing materials on the market to make something new: a drug delivery system called Intra Cavity Drug Retention (ICDR) that stays liquid outside the body at room temperature, and becomes a sticky gel only once it’s inside the body.

The gel defies some basic scientific laws regarding the behavior of materials. Normally, gels become liquid with heat, not the other way around. But this oddity can benefit humankind and is already undergoing advanced clinical trials in Europe, where Theracoat’s material is classified as a medical device.

“This discovery is like many others — when you find something in one field like in chemistry, and one can find other uses in other fields, like medical,” Hakim tells ISRAEL21c. “The founders of the company joined these two worlds of chemistry and medicine. In cancer, there is a big unmet need.”

This is especially true in bladder cancer, where there are high rates of reoccurrence.

A more pleasant patient experience

When people are going for rounds of chemotherapy to treat bladder cancer, they have to move around “like a barbecue” to make sure the bladder walls get coated with the cancer drug, says Hakim. This uncomfortable treatment takes a long time, and often a larger dose than necessary is given in order to make sure it coats the entire area.

Delivering the drug with the ICDR system requires using less active drug, and making what’s catheterized into the bladder stick onto the target tissue of the bladder walls. A person can pop in for a treatment and then leave the clinic right away; no gymnastics necessary.

“It is too early to say just how much better we can treat cancer,” says Hakim, but he hopes when clinical results come in, the company will be able to stand behind some impressive data. The material is already available in Europe with a CE mark for drug companies to license. Theracoat is hoping to sell it as a platform to help existing pharmaceutical companies provide a new and better way for delivering their drugs to any cavity in the body.

Theracoat’s material can be a novel solution to any kind of treatment where a drug needs to be piped in and stay put inside a cavity, such as for drugs that target malignancies in the uterus, the colon, the bowel, the stomach, the eye or the sinus, says Hakim.

But the company had to start somewhere and bladder cancer was a good place due to the unmet need.

In this regard, in the United States the company is working toward an orphan status drug indication for treating upper urinary tract urothelial cell carcinoma, a rare kind of cancer that is usually treated by removing a kidney –– not an optimal solution.

“Now we might be able to give the option of killing the cancer, because the gel stays there and releases the drug. This is a much worse cancer for people to have than if the cancer is in the bladder,” says Hakim.

Overcoming the nature of things

Orphan status is given to drugs that could help rare conditions, and as such they are pushed past the Food and Drug Administration’s regulatory hurdles much faster than other new drugs that must be tested more thoroughly. The rationale is that people might die waiting for a solution, so an orphan drug at least might give them a chance to live longer.

The big questions that healthcare professionals have are just how effective is Theracoat’s gel to help deliver drugs to internal cavities, and does this make a difference in outcomes for patients?

In fact it was a urinary oncologist in Israel who approached one of the Theracoat founders, Asher Holzer, about 10 years ago. The doctor was treating people for bladder cancer, and asked Holzer if there was a material that could help cancer drugs stick better to the bladder wall.

Due to the nature of things, our bladders are constantly voiding liquids so it’s not a trivial matter keeping active compounds in the bladder for the time needed to treat effectively. Holzer asked a chemist friend of his, Dorit Daniel, if there was anything on the market that might help and she knew of some materials. That got them thinking, and this was the precursor to Theracoat.

Incorporated since 2004, Theracoat has pretty much been off the biotech news radar until now because it had been operating on stealth mode. Based in Ra’anana, it has a team of 15 running on about $8 million. The company is now closing a new round of funding but is always open to financial inquiries, Hakim says. It also currently seeks strategic partnerships with pharmaceutical companies interested in testing out the Theracoat formulation.

The company is testing its material in bladder cancer chemo in Europe and is about to start trials in Israel; and is also testing it with drugs against overactive bladder in both locations. Solutions for bladder cancer and for incontinence are expected to be ready in 2014.