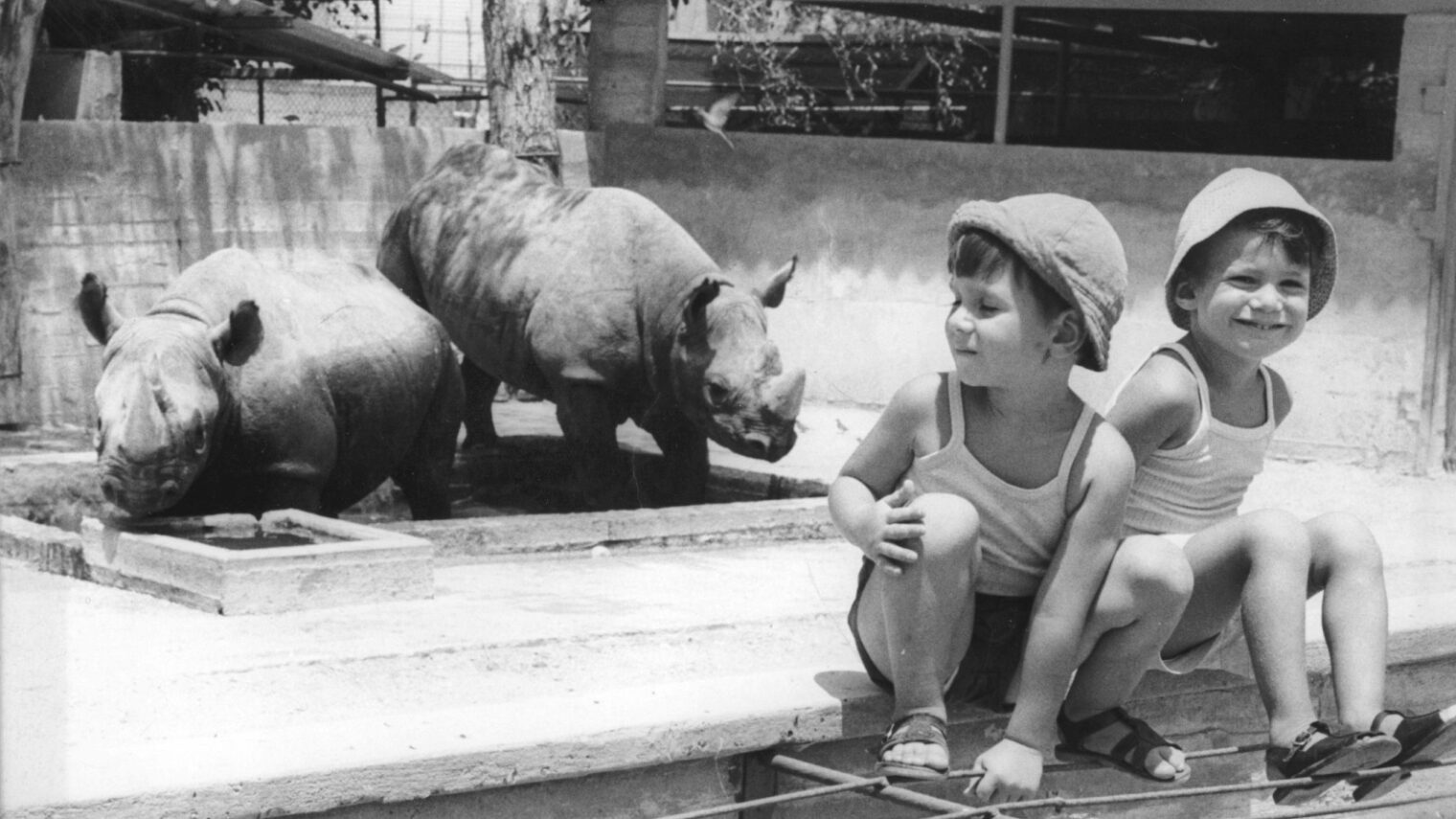

Mazal tov! A new baby white rhino was born last week at the Ramat Gan Safari. The new calf – named by popular vote Kamili, which means “perfect” in Swahili – joins her mother, Keren Peles, and sister, Kifanzi.

Kamili is the 31st rhino birth at the Safari, which is the leading European breeder of rhinoceroses in captivity. Given the Safari’s humble roots, that is nothing short of a modern-day miracle.

In 1935, a small pet shop opened at 15 Sheinkin Street in central Tel Aviv. The proprietor, Rabbi Dr. Mordecai (Max) Schornstein, the 66-year old former chief rabbi of Copenhagen, had acquired some animals in Italy while en route to pre-state Israel.

The store, called “Gan Hayot” (“zoo” in Hebrew) sold animals and bird food, and quickly became an attraction for the 120,000 residentsof the fledging city.

In 1936, he was invited to exhibit caged animals at the Levant International Fair at the Tel Aviv Fairgrounds, and the idea for a Tel Aviv Zoo was born.

In catalog notes to the 2009 Eretz Israel Museum exhibit, “Memories of the Zoo – Tel Aviv, 1938-1980,” curator Batya Donner wrote, “The extent and pace of the urban development of Tel Aviv, its vibrant streets, cultural institutions, shops, stores, and cafes made it into a city that realized the dreams of its founders. Against this backdrop, one can easily understand the decision of the Tel Aviv Municipal Committee to lease a plot of land of a dunam and a half on behalf of Dr. Mordechai Schornstein in order to build a zoo.”

Schornstein’s first zoo was located at 65 Hayarkon Street (today adjacent to the Tel Aviv branch of the US Embassy) but the ever-growing collection of animals – including donations of lions and tigers – gave rise to complaints by the neighbors, “…and thus Dr. Shornstein approached the Tel Aviv Municipality, helped by the ‘Animal Lovers Association’ and backed by a petition signed by 1,139 city residents… requested to lease a new site in order to build a zoo.”

A location was selected somewhat outside the city center, bordering on Shlomo Hamelech Street and Keren Kayemet Boulevard (today Ben Gurion Boulevard). This was the Portalis orange grove, land that had been purchased by the municipality in 1925.

When the 1936 Arab riots broke out, the grove was declared a danger zone and the trees – which did not bring in significant profit – were uprooted, and the area slated for development. The new zoo, designed by the modernist architect Leopold Lustig (who apparently provided this service free of charge), opened its gates to the public in December 1938.

In 1939, after a plan to build a municipal hospital on the site did not come to fruition, the entire area was designated a public park, called Gan Hadassah, which included a municipal swimming pool at one end and the zoo at the other.

Initially, Schornstein worried that the distant location, so far from the city center, would discourage attendance, and demanded the municipality provide free advertising on buses and billboards. His fears were unfounded as, even in its first year of operation, the zoo had some 50,000 visitors.

People came from all over the country to marvel at the animals. These included, as this 1938 newsreel declares enthusiastically, “the Himalayan-born bears [from] Calcutta, a gift of the Doctor Grilzhammer and the engineer Wolf, [have] many good attributes: intelligent, very jolly, and amuse the children with their gaiety and movements as quick as a monkey’s.”

Interestingly, the newsreel notes that the lions, Gibor and Tamar, “were born in the Cairo Zoo, and while still young were brought here as a gift from the Egyptian government.”

The native-born “sabras,” the newsreader proudly declared, were a pair of hyenas, “brought here from the Carmel mountains, a gift from the daughter of zoo director Dr. Schornstein, who is conversing with his student, the parrot.”

A strange interlude

But all did not go smoothly. Schornstein and the Animal Lovers Association had initially agreed on the transfer of ownership of the animals in return for their upkeep and housing in the new location, plus a salaried position for Schornstein as zoo director.

But a conflict arose in 1939 that led to his demanding that the contract be canceled. The association withheld his salary and the municipality forbade Schornstein from selling pets. Schornstein grabbed three lira in cash from the zoo till in lieu of salary, which then led to a police complaint, a trial for theft, conviction and bail.

Finally, in 1941, an arbitration agreement stipulated that Schornstein not sell animals and birds from the zoo. In return, he would receive a monthly stipend and free entry to the zoo for the rest of his life. He was also promised that if his behavior towards the association was satisfactory, his legacy would be perpetuated with a plaque at the zoo’s gates.

With the court case settled, Schornstein moved to the Beit Hakerem neighborhood in Jerusalem where he established a bird sanctuary. In 1947 he moved to Netanya, where the local council granted him a plot of land to establish a petting zoo. He died at the age of 80 in October 1949.

The new zoo

Schornstein’s successor, Baruch Gofer, who took over zoo management in 1942, proved as talented as his predecessor in being able to obtain new species, fundraising in the Jewish world and, after World War II, animal exchanges with European zoos in cities like Vienna, Berlin and Warsaw.

Jewish and Arab residents were also actively involved. According to Donner, “People would offer the zoo animals they hunted and caught in the Galilee and the Negev, and would consult the zoo employees about taking care of the animals. To increase the number of animals in the zoo, its employees often made unusual appeals to different people, such as Jewish Brigade soldiers who fought with the British Army in North Africa, and asked them to bring back baby predators.”

Gofer, a former police officer and commander, was an adept administrator. As it turned out, the zoo became his passion; he was a great believer in the zoo as a cultural-educational tool to teach young people about love of nature and, later in life, authored several books about his tenure at the zoo.

Over the decades, the zoo expanded to cover an area of 34 dunams (8.5 acres). According to the Encyclopedia of the World’s Zoos, “…the zoo was famous in the 1960s for its breeding flock of greater flamingos and, later, for its breeding of the Waldrapp ibis.”

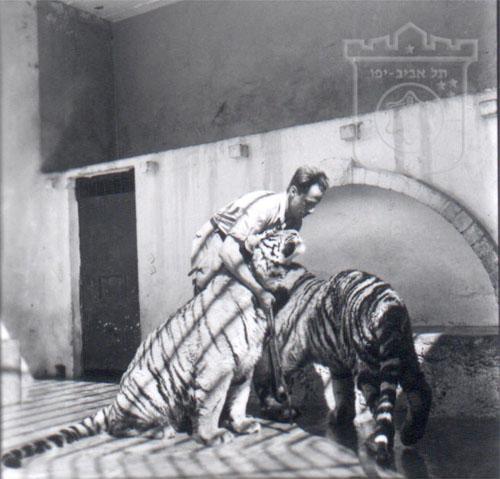

In addition to the monkeys, which were famous for their mischief, the zoo also had its share of human “characters.” The ticket vendor, known as Weinberg, plastered himself with ads for the zoo. The lion-taming zookeeper Jonny (Joachim) Souchier, a French Huguenot convert to Judaism and ex-kibbutznik, had begun working with Schornstein at the pet store.

According to the Tel Aviv Municipal Archive, “At the end of the 1940s, a small house was built for him at the zoo where he lived with his wife Nora… Jonny had a special love and attitude for the big cats, lions and tigers, and used to walk with them, enter their cages freely, embrace them and have them embrace him. Nora was especially interested in cubs and small animals like foxes, squirrels, deer and kangaroos. Medical supervision was given to Dr. Levitt, Tel Aviv’s veterinarian.”

Moving and merging

Unlike the old days when it was on the city outskirts, by the 1960s, the zoo now stood at the center of a densely-populated residential area, right next to Malchei Yisrael Square (today Rabin Square) and the newly built Tel Aviv City Hall.

Israeli humorist Ephraim Kishon joked that one day an escaped lion entered City Hall and began eating clerks one by one, but no one noticed until he ate the tea-cart lady.

It was decided to relocate the zoo to Yarkon Park but despite a cornerstone-laying ceremony, that new Tel Aviv Zoo was never built and by the 1970s, the zoo had become a liability.

The physical spaces for the animals were no longer acceptable according to modern zoo practices. Neighbors complained about noise, smell and traffic jams – especially on Saturdays when the zoo was open to the public for free. In addition, the price of Tel Aviv real estate was going up and the former orange grove was now an extremely valuable property.

Meanwhile, in the neighboring city of Ramat Gan, a small children’s zoo had been established in 1958. In the late 1960s, founding director Zvi Kirmeier was inspired by the newly developing concept of wildlife parks or safari parks, where visitors in vehicles observe freely roaming animals.

The idea to found a safari park in Ramat Gan was approved by the first mayor of Ramat Gan, Avraham Krinitzi, and followed-through by his successor, Dr. Yisrael Peled.

As told in the Encyclopedia of the World’s Zoos: “After Kirmeier, Peled and the project’s landscape architect, Zvi Miller, made trips to Africa and consulted with game experts, the [children’s] zoo at Ramat Gan was expanded in 1974, at the expense of the national park, to form the Ramat Gan Zoological Park Corporation… Eventually, the compelling logic of combining the Tel Aviv Zoo collection with the safari, rather than maintaining two competing sites, resulted in the planning of the 45-acre (18 hectare) zoo within the Ramat Gan Zoological Park.”

The Tel Aviv Zoo closed its doors in 1980 and the animals transferred to the safari park. The new zoo within a drive-through safari, designed by Israeli landscape architect firm Miller-Blum-Lederer, opened in 1981.

Today, the Ramat Gan Safari (officially known as the Zoological Center Tel Aviv-Ramat Gan) is the largest collection of wildlife in human care in the Middle East.

The 250-acre site consists of both a drive-through African safari area and a modern outdoor zoo. It is the home of 83 species of mammals, 92 species of birds and 23 species of reptiles. It hosts over 700,000 visitors every year.

Among other outstanding groups of animals are white rhinos – including new baby Kamili–as well as hippos, lions, African and Asian elephants, gorillas, orangutans and a Komodo dragon.

The Safari participates in dozens of international and local endangered-species breeding programs and has outstanding breeding records for both African and Asian elephants, as well as white rhinos.

It also serves as the location for the Israeli Wildlife Hospital, a cooperative enterprise between the Ramat Gan Safari and the Israel Nature and Parks Authority.

As for the old Tel Aviv Zoo, the $2.5 million construction costs of the new zoo were funded with part of the proceeds from the sale of the property.

Today, the luxury GanHa’ir residence tower and shopping mall stand on the site. In the shadow of the tower is a small public park with a statue dedicated to Rabbi Dr. Mordecai Schornstein.

It’s fair to assume that, even though he was something of a visionary, Schornstein could not have imagined the amazing accomplishment that all started with his small pet shop and modest zoo.

![Elections 1977 – Likud posters] In 1977, Menahem Begin led an election upset as Israel’s first non-Labor prime minister. Credit: GPO Elections 1977 – Likud posters] In 1977, Menahem Begin led an election upset as Israel’s first non-Labor prime minister. Credit: GPO](https://static.israel21c.org/www/uploads/2019/09/Elections_1977___Likud_posters_-_GPO-768x432.jpg)