The Jewish New Year 5775 is also a year of shmita, the sabbatical year of the seven-year cycle mandated by the Torah for all agricultural produce grown the Land of Israel. Like most things related to the seemingly benign occupation of farming, shmita is a hot-button topic, particularly over the past 132 years since the 1882 First Aliya — also known as the Farmer’s Aliya — and the introduction of modern agricultural methods to the Land of Israel.

As defined in Wikipedia, “During shmita, the land is left to lie fallow and all agricultural activity, including plowing, planting, pruning and harvesting, is forbidden by halakha (Jewish law). Other cultivation techniques (such as watering, fertilizing, weeding, spraying, trimming and mowing) may be performed as a preventative measure only, not to improve the growth of trees or other plants. Additionally, any fruits which grow of their own accord are deemed hefker (ownerless) and may be picked by anyone. A variety of laws also apply to the sale, consumption and disposal of shmita produce. All debts, except those of foreigners, were to be remitted.”

In 1888-9, the debate over how to handle shmita turned into a personal and sometimes ugly rivalry between the existing Yishuv and the new settlement. In an essay published by the Jewish Journal, entitled Rav Kook – The Shmitta – and Personal Release, Rabbi John Rosove writes:

“Since the laws of both Shmitta and Yovel only apply in the land of Israel, and Yovel applies only when all the Jewish people are living in Israel, until the Zionist movement Shmitta and Yovel mattered little to Diaspora Jewish communities.”

“However, Zionists complained that if farmers did not work the land the nascent settlement movement’s existence would be threatened. In response, lenient rabbinic authorities justified setting the laws of the Shmitta year aside based on the principle of sha’at hadechak (“undue hardship”).”

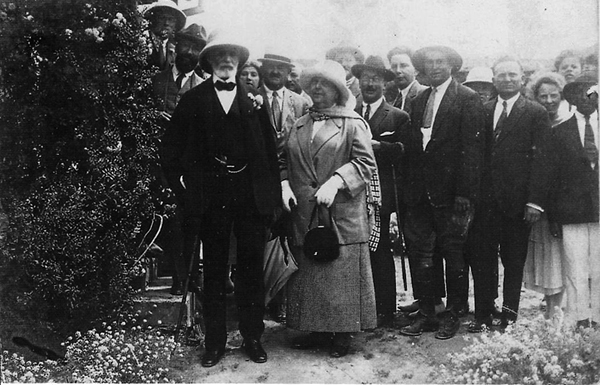

This tense situation was detailed in an essay by Rabbi Dr. Chaim Simons: “There were some colonists who observed the Shemittah. However it was not easy for them since great pressure was put on them from various sources. One of these sources was the overseers of Baron Edmond Rothschild who was helping to financially support the new settlers.

“A further source of compulsion was the leaders of Hovevei Zion who stopped giving financial support to the Shemittah observers. On this Dr. Leon Pinsker, one of the founders and leaders of ‘Hovevei Zion’ wrote, ‘I gave an order to stop supporting the community of Gedera if they do not work during Shemittah.'”

“There were even people ‘who were not ashamed to involve the [Turkish] government in this matter and they went and informed against them [the Shemittah observers] to the authorities saying that the Jews were not working and would thus harm the treasury.’ Only a few of the colonists were able to withstand this pressure.”

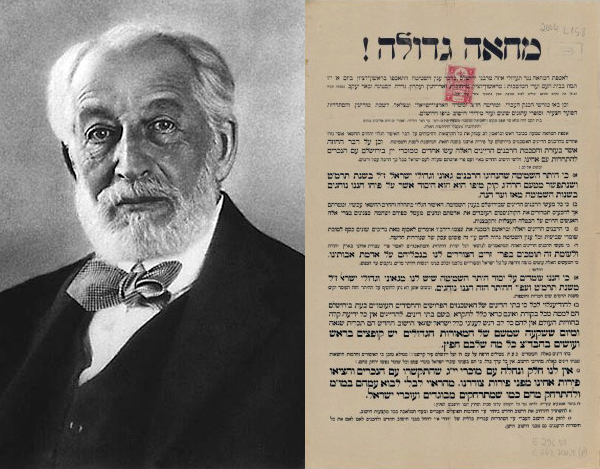

The solution arrived at for the Shmita year of 1888-9 was a rabbinic document known as a Heter Mechira (“Sale Permit”) that allowed Jewish farmers to sell their land to non-Jews, similar to the contracts for selling leavened products to non-Jews before Passover. With Heter Mechira, Jews could continue working the land. With the end of the shmita year, ownership reverted automatically back to the former owner.

The mechanism was supposed to be a one-time thing but — like so many things Israeli — has persisted throughout the decade and not without controversy, whether over hydroponically grown produce or the role of local rabbinical courts in approving the Heter Mechira. There is always something.

The National Library of Israel has digitized its collection of posters and historical documents relating to the ongoing debate over shmita, and presented it together with links to contemporary Hebrew-language newspapers.

Interestingly, this year the Jewish community both in Israel and the Diaspora have seized on shmita as an opportunity to introduce positive communal values into the public discourse.

So, for example, the Hazon organization’s Shmita Project is “working to expand awareness about the biblical Sabbatical tradition, and to bring the values of this practice to life today to support healthier, more sustainable Jewish communities.”

In turn, Hazon partner Teva Ivri, a non-profit organization promoting Jewish environmental responsibility in Israel, established the Shmita Yisraelit, the Israeli Shmita Initiative, a platform of individuals, NGOs, government officials, and corporate executives from all points on the Jewish spectrum.

Shmita Yisraelit supports re-positioning the shmita year as a “reset year”, a time of personal reflection, learning, social involvement, and environmental responsibility in Israel. The initiative challenges Israelis to “change the rules of the game in the race of life”. Will it work? We have a year to find out.