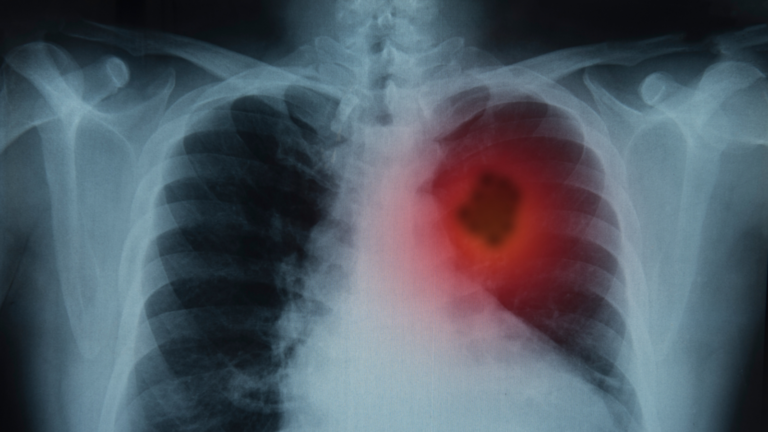

Researchers may have found an effective, relapse-free way to treat lung cancer.

A team at Israel’s Weizmann Institute of Science believe they’ve identified a treatment likely to bring about full remission for some patients.

They say an existing drug called Erbitux, used currently for cancers of the colon, neck and head, could be suitable to treat the gene mutation found in 40 percent of non-smoking lung cancer patients.

In tests on mice, they were able to “short-circuit” the switch that drives abnormal cell growth, so that tumors shrank permanently.

Critical to their research was the discovery of a biomarker – the cell’s early-warning system – which tells them which individual patients are likely to respond positively to Erbitux.

Details of their findings were published August 8 in the journal Cell Reports Medicine. The team’s next step will be clinical trials to establish the treatment’s effectiveness on human patients with lung cancer.

“We have found a potential biomarker that may change the way patients with lung cancer are treated worldwide,” said study leader Prof. Yosef Yarden of the institute’s Immunology and Regenerative Biology Department.

“The new biomarker might make it possible to match some lung cancer patients with the specific medication most likely to help them.”

Sorting by mutation

Most lung cases are caused by smoking, but the second biggest cause is the mutation of the gene EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor).

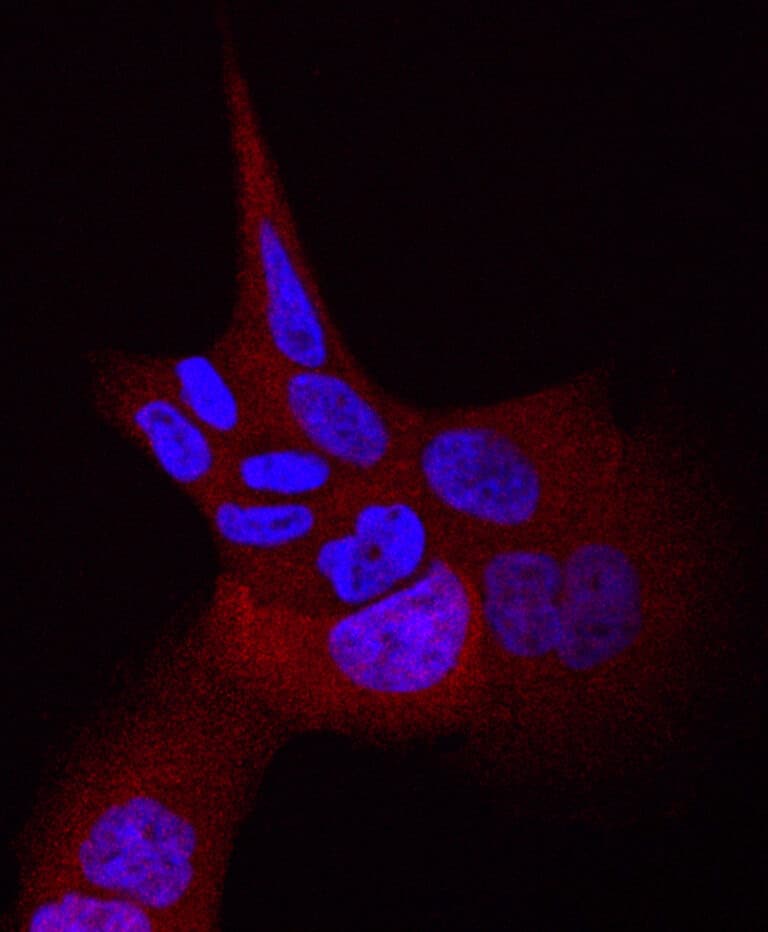

EGFR helps cells grow and divide, but if there’s a mutation – a typo in its DNA – it can get stuck in the “on” position.

There are around 30 of these mutations, all with a slightly different typo, but all currently treated with the same cocktail of drugs.

Yarden’s team found that patients with EGFR mutations initially responded very well to the treatment, but eventually developed resistance to the medication and suffered a relapse.

The drugs stopped working because the tumors started acquiring secondary mutations.

Dr. Ilaria Marrocco, then a postdoctoral researcher in Yarden’s lab, reviewed the literature from clinical trials and wondered whether, by sorting lung tumors according to specific EGFR mutations, it might be possible to create a more personalized drug protocol and achieve better results.

“Dr. Marrocco’s observation inspired us to search for a biomarker that would predict which patients would respond well to therapy, according to the specific mutations they carry,” said Yarden.

They focused on a particular mutation called L858R, one of the two most common gene variants associated with EGFR in lung cancer.

They found that Erbitux – a drug developed based on research by Yarden and others – successfully blocked proteins that pair up and signal the cell’s nucleus to start replicating and keep on replicating.

“We discovered that, if this pairing does not occur, it’s like a short-circuit – the signal to initiate cellular replication cannot be sent to the nucleus, and the tumor does not grow,” said Yarden.

EGFR inhibitors were approved as lung cancer drugs nearly 10 years ago, and are routinely prescribed to patients, regardless of the type of gene mutation.

“By the time Erbitux is given, it is usually ineffective because it can work only against certain EGFR mutations,” said Yarden.

“Our study demonstrates the importance of pre-selecting lung cancer patients who can be effectively treated with Erbitux from the start, based on their mutation profile.”