An Israeli professor’s recent article in the American Journal of Climate Change is making waves for its suggestion of how to standardize global testing of pollution levels toward a better understanding of how smog affects the weather.

Working with graduate student Olga Shvainshtein and scientist Pavel Kishcha, Prof. Pinhas Alpert of Tel Aviv University’s Department of Geophysics and Planetary Sciences pored over eight years’ worth of comprehensive data from three NASA aerosol-monitoring satellites to track pollution trends in 189 large cities, including New York City, Tokyo and Mumbai.

Spread the Word

• Email this article to friends or colleagues

• Share this article on Facebook or Twitter

• Write about and link to this article on your blog

• Local relevancy? Send this article to your local press

They discovered that Northeast China, India, the Middle East and Central Africa suffered the highest increases in atmospheric pollutant particles between 2002 and 2010, while Europe and northeast and central North America are experiencing the greatest decreases in aerosol concentrations. The air over Houston, Texas; Curitiba, Brazil; and Stockholm, Sweden, is slowly getting cleaner.

Alpert, who heads the university’s Porter School of Environmental Studies, will offer results of the accumulated satellite data for the United Nations and individual governments to use in planning and policy to combat dangerous aerosol pollution. His findings have been reported in consumer publications such as USA Today and The Economic Times of India.

Sometimes it takes an outsider

Alpert chuckles when asked why nobody else had thought to put all the data together for a comprehensive report card on global pollution. He relates that when he presented his idea to 100 NASA algorithm developers last July, this was the question on everyone’s mind.

“They were amazed that somebody from the ‘outside’ came and did this,” says Alpert.

But he explains that NASA, where he once spent a sabbatical year, was reluctant to rely on data from the satellites because of known flaws in each individual system.

“Indeed, each instrument has its own problems that are not necessarily the same as the others,” the atmospheric scientist tells ISRAEL21c.

“But when you collect from the three instruments together, in spite of their different algorithms and instrumentation and angles from space, their flaws are mostly counterbalanced and they do agree concerning most of the cities in the world. Sometimes there is agreement between two of the three, and in such cases we suggested looking at the majority. In the Jewish tradition, individual judges don’t decide cases. There must be a minimum of three. You need a majority opinion.”

Alpert’s ongoing research in cooperation with NASA scientists supports his guess that alarming increases in pollution over Portland, Oregon, and Seattle, Washington, was caused by multiple wildfires in the region during the second half of the period examined. Now he wants to understand how to quantify separately the pollution caused by the fire itself and pollution caused by hazardous litter, including plastic, which burned in the fire.

“Using the same algorithm to calculate for the whole world, we can really get more objective methodology for monitoring pollution,” he says, “but first we must address problems such as fires.”

Will it rain? Check with your nearest cell-phone tower

At the same time, Alpert is continuing to work on his unique flood-warning system that in 2009 won him a Popular Science award.

This project was spurred by the difficulty in accurately measuring rainfall intensity and moisture levels near flood-prone zones such as the deserts of the Negev and the Dead Sea. Moisture in the atmosphere causes fluctuations in radio and microwave signals around cellular towers, and Alpert realized that these measurements could help provide early warning.

“We have a paper conditionally accepted, to be published soon, showing that employing data from cellular towers can give an advance warning of a few minutes or an hour about rainfall in regions prone to flooding,” he says.

“In semiarid areas there are few rain gauges, and radar is not so effective in monitoring rainfall in the valley. Cellular towers are more efficient because they have long lines connecting them that measure the existence of water between them. Knowing about it even a few minutes in advance can save lives because in the desert, it’s common that rainfall is very local but still can cause flooding.”

The Israel Meteorological Service is very interested in this approach, says Alpert, and is awaiting results from several test sites he has set up.

“We are now studying snowfall and hail as well, but we do not yet have the possibility of giving advance warning on that. In the future, by using data collected from cell towers, we could improve hail and snow forecasts as well.”

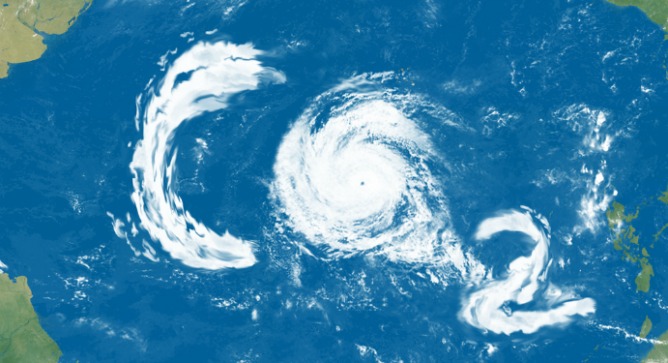

*Image via Shutterstock.com