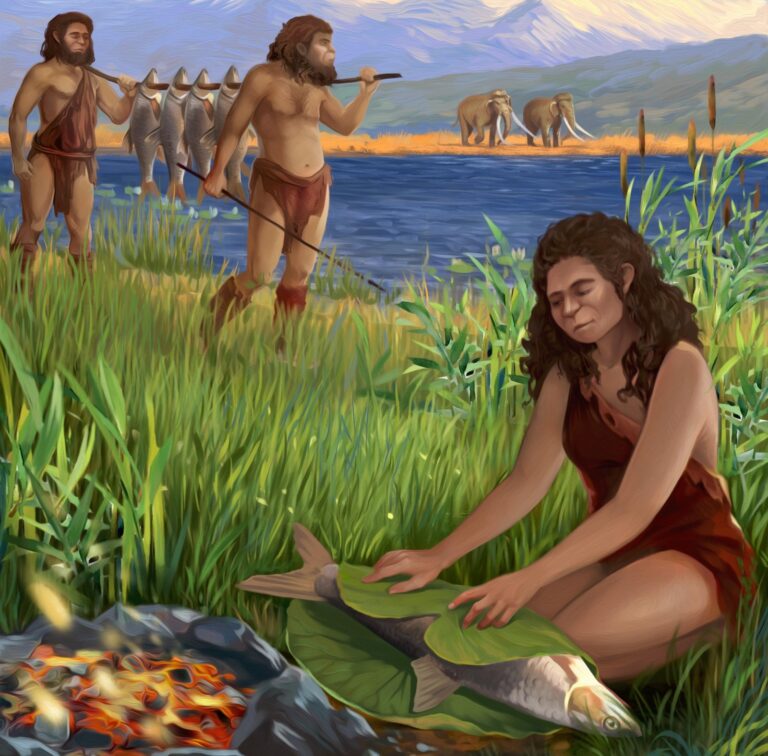

The remains of a gigantic carp-like fish cooked roughly 780,000 years ago has just changed the answer to the question of when humans began using fire in a controlled way to cook food.

Until now, the earliest evidence of intentional cooking dates to approximately 170,000 years ago.

The 2-meter (6-foot) fish was discovered at the Gesher Benot Ya’akov (GBY) archeological site in Israel and analyzed by experts from the Hebrew University, Bar-Ilan University and Tel Aviv University in collaboration with Oranim Academic College, the Israel Oceanographic and Limnological Research institution, the Natural History Museum in London, and the Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz.

Their remarkable findings were published today in Nature Ecology and Evolution.

Evidence of a cooking fire at the site—the oldest such evidence in Eurasia—was identified first by BIU Prof. Nira Alperson-Afil.

“The use of fire is a behavior that characterizes the entire continuum of settlement at the site,” she explained. “This affected the spatial organization of the site and the activity conducted there, which revolved around fireplaces.”

Coauthor Irit Zohar from TAU’s Steinhardt Museum of Natural History, curator of the Beit Margolin Biological Collections at Oranim Academic College, said, “This study demonstrates the huge importance of fish in the life of prehistoric humans, for their diet and economic stability. Further, by studying the fish remains found at Gesher Benot Ya’akov we were able to reconstruct, for the first time, the fish population of the ancient Hula Lake and to show that the lake held fish species that became extinct over time.”

HU Professor Naama Goren-Inbar, director of the excavation site, said the large quantity of fish remains found at the site proves their importance in the diet of early humans.

“These new findings demonstrate not only the importance of freshwater habitats and the fish they contained for the sustenance of prehistoric man, but also illustrate prehistoric humans’ ability to control fire in order to cook food, and their understanding the benefits of cooking fish before eating it,” Goren-Inbar said.

She added that this is “another in a series of discoveries relating to the high cognitive capabilities of the Acheulian hunter-gatherers who were active in the ancient Hula Valley region. … Gaining the skill required to cook food marks a significant evolutionary advance, as it provided an additional means for making optimal use of available food resources. It is even possible that cooking was not limited to fish, but also included various types of animals and plants.”

Zohar and Prof. Israel Hershkovitz from TAU’s medical school noted that the transition to eating cooked food had dramatic implications for human development and behavior.

Eating cooked food reduces the bodily energy required for digestion, allowing other physical systems to develop. It also leads to changes in the structure of the human jaw and skull. Without the daily, intensive work of searching for and digesting raw food, early humans had free time in which to develop new social and behavioral systems.