There’s the West Nile Virus forging a deadly path in North America, and a new round of Ebola in Africa. Then there’s bird flu, SARS and a handful of other rampant and unusually evil viruses circling the globe. Any new super virus out of control could be far worse than the Spanish flu outbreak of 1918, which killed 40 million people in just two years, says Israeli biologist Erez Livneh, CEO and founder of a new biotech company Vecoy Nanomedicines.

“Viruses are one of the biggest threats to humankind,” Livneh tells ISRAEL21c. “A viral pandemic could be more damaging than global warming or the Iranian nuclear program.”

Spread the Word

• Email this article to friends or colleagues

• Share this article on Facebook or Twitter

• Write about and link to this article on your blog

• Local relevancy? Send this article to your local press

Vecoy offers a cunning new way to disarm viruses by luring them to attack microscopic, cell-like decoys. Once inside these traps, the viruses effectively commit suicide.

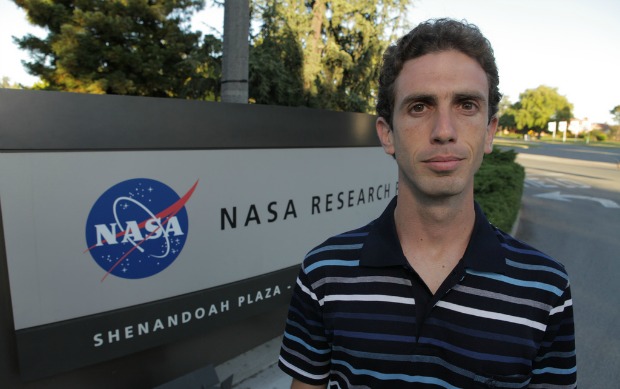

Livneh presented his invention to colleagues in 2010, when he represented Israel at the multinational program of the Singularity University, based at NASA’s Ames Research base in California. He explained that Vecoy technology can capture and neutralize a wide range of deadly viruses, including resistant strains for which there are no vaccinations or cures.

“Viruses are one of the most polymorphic and resilient organisms out there,” says Livneh. “They are rapidly changing, and can change anything in their genome, either by changing their exterior so our immune system wouldn’t recognize them or by changing their enzymes so that the handful of drugs we have won’t affect them anymore.”

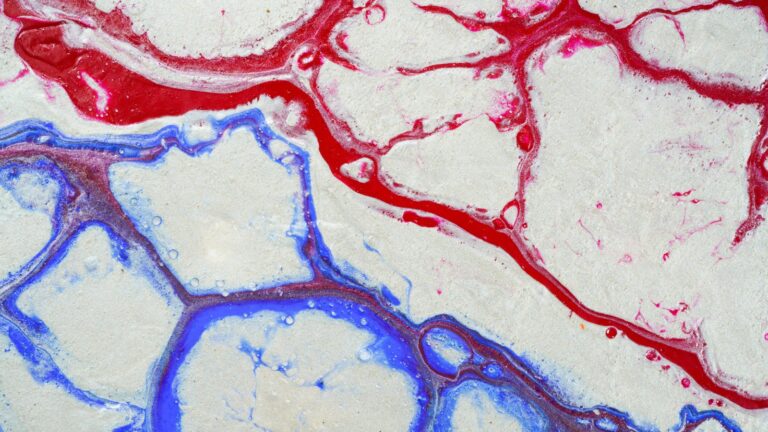

Yet all viruses, he notes, have one unchangeable Achilles heel: their cell host recognition site. Vecoy uses nanotechnology to give the virus two choices: either latch on to the Vecoy host trap or mutate in such a way that it cannot penetrate real host cells. In both scenarios, the end result is bad news for the virus.

“That is why, in theory, a virus cannot develop adaptive resistance to our traps,” says Livneh.

A cure, not just damage control

While vaccines, a 200-year-old invention, are a great prophylactic and have largely eradicated polio and smallpox, some viruses, such as HIV, elude vaccines. And anti-viral drugs attempt to block viruses from multiplying further from already infected cells.

“The trouble is, this is a bit too late; it’s damage control more than a cure,” explains Livneh. “Our virus-traps meet the viruses on their turf, in the bloodstream where they are disarmed before they reach the cells and before the damage is done.”

While it takes years to come up with new drugs, Vecoy’s virus traps could be tailored to address emerging new viral outbreaks quickly and efficiently, even in the event of a bioterror assault. If a government sees a threat coming from an enemy nation or a potential pandemic blowing its way, Vecoy’s solution could potentially inoculate populations before peril arrives.

“With the current state of overpopulation of our planet and international flights, we are now prone more than ever before to new viral pandemics which will be very hard to contain, and it is just a matter of time,” warns Livneh. “We’d better be in a position where we can do something about it.”

Treating the usual suspects too

Besides Ebola and new emerging and highly contagious viruses, Vecoy is also targeting the usual ones many of us struggle with every day, including hepatitis B and C, the human papillomavirus and herpes. New, smarter weapons are needed against all these viruses.

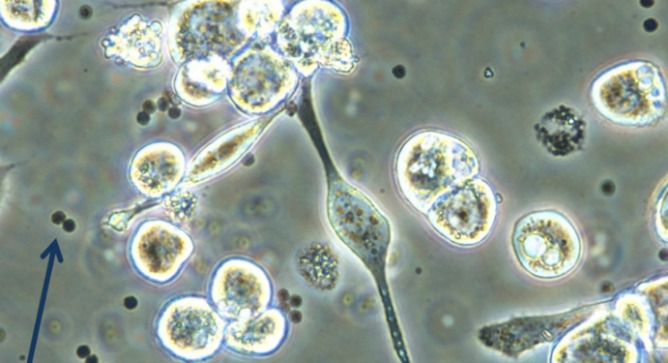

Results of cell-culture and pre-clinical studies in Vecoy’s laboratories at Bar-Ilan University’s nanotechnology center are promising, showing the neutralization of 97 percent of the viruses in the culture. Efficacy is expected to rise even further.

With an international patent pending and secured angel investments, the company now seeks several million dollars to begin studies on mammals, the next step before clinical trials in human beings.

While the road is long –– at least four or five years to start clinical trials –– it is a path worth taking if these Israeli-made virus decoys can do the job.

If Livneh succeeds on his quest he will no doubt go down in the history books along with Louis Pasteur (for pasteurization), Sir Alexander Fleming (for penicillin) and Jonas Salk (polio vaccine).