Cancer is a devious adversary. It figures out all kinds of ways to hide from the body’s detection systems and grow unchecked until it’s too late to stop them.

One of cancer’s most cunning methods of evading the immune system is to increase the frequency of a kind of cellular “train” – a protein called XPO1 – that makes regular back-and-forth trips in and out of the nucleus of a cell. The XPO1 protein’s job is to shuttle other proteins to the right stops on the line.

One passenger on the XPO1 shuttle is a tumor-suppressing protein. Its job is to conduct regular “audits” of a cell to ensure the DNA is not damaged. If it is, the protein instructs the cell to enter“programmed cell death,” whereby the cell essentially commits suicide.

Cancer cells, by their very nature, have damaged DNA – that’s what causes them to divide uncontrollably, creating tumors. In a healthy immune system, the tumor-suppressor proteins would catch the DNA mistakes in the nucleus and stop the cells from proliferating.

But cancer outwits the tumor-suppressing proteins by increasing XPO1 activity. More frequent trains take the suppressor proteins out of the nucleus of the cell – where they should be stopping the cancer – and deposit them far away.

“They can’t do their job because they’re geographically removed from where they’re supposed to be,” says Sharon Shacham, CEO of Karyopharm Therapeutics, an Israel- and Massachusetts-based company that has developed a new drug that inhibits XPO1 activity in a cell. “We stop the train from taking the passengers.”

When there’s nothing left to try

Karyopharm recently was awarded FDA approval for XPOVIO, the first drug to slow down the XPO1 train so that the body’s natural tumor-suppressing proteins can do their job.

XPOVIO (generic name Selinexor) has been approved for multiple myeloma patients who have relapsed and were resistant to at least four prior therapies.

XPOVIO for multiple myeloma was approved according to the FDA’s fast-track designation, which grants a quicker time to market for drugs addressing rare diseases or those for which there is no cure.

Multiple myeloma, the second most common type of blood cancer after non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, can be slowed by medication – often going into remission for years – but ultimately it always returns and progresses. When a patient has gone through all of the available options, there’s nothing left to try. Enter XPOVIO.

Because of its dire prognosis, multiple myeloma was the starting point for XPOVIO, but it’s far from the end game.

“Most cancer cells have XPO1 overexpressed,” Shacham tells ISRAEL21c. “We are planning to submit XPOVIO for approval with lymphoma next.”

If the results are positive, Karyopharm will move on to test XPOVIO with various types of sarcoma, earlier lines of myeloma, uterine cancer and brain cancer, Shacham says.

Shacham is quick to point out that XPOVIO can’t be declared a cure for multiple myeloma – at least not yet. It simply hasn’t been around long enough, although patients “are seeing long-term benefits,” she says.

Nor is XPOVIO side-effect free. Nausea, vomiting, fatigue, low white blood count and anorexia are all common. “It’s outlined in the label,” she points out. “But with supportive care, patients can stay on XPOVIO.”

The drug doesn’t come cheap: it costs $22,000 for a four-week supply, although patients approved for the drug by their health-insurance plan won’t need to pay the full amount.

Overall response rate of 25.3%

Karyopharm has been running at a marathon pace against cancer over the past decade.

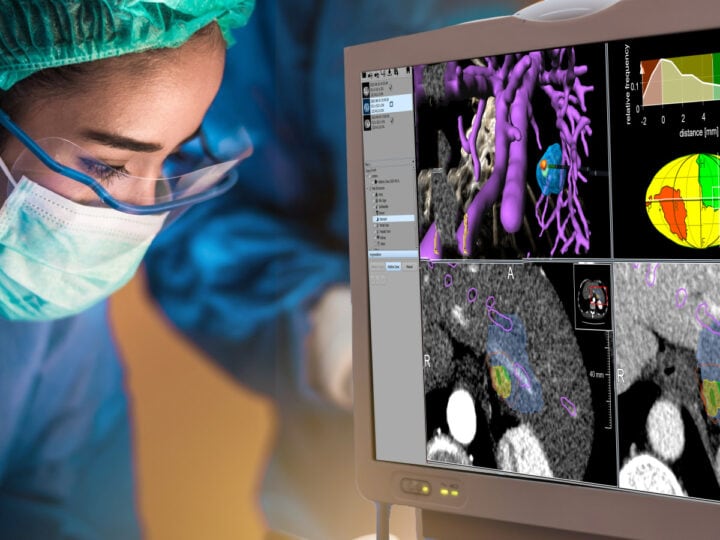

More than 3,000 people have gone through clinical trials in 20 company-sponsored studies and another 50 studies run by individual investigators looking at the drug either as a single agent or in combination with other medicines including dexamethasone, a steroid commonly used as part of chemotherapy.

For FDA approval of XPOVIO for multiple myeloma, 83 patients were tested with the drug plus dexamethasone. The median time to first response was four weeks with a median duration of response of 3.8 months.

The overall response rate at the end of the study was 25.3%, which “is clinically meaningful and a validated surrogate marker for clinical benefit in our patients with advanced refractory disease,” said Dr. Sundar Jagannath, director of the Multiple Myeloma Program at the Tisch Cancer Institute at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York.

Shacham received her PhD in computational biophysics from Tel Aviv University in 2000. She founded biotech firm Predix upon graduation; Predix merged with Epix Pharmaceuticals in 2003.

Shacham launched Karyopharm 10 years ago with headquarters in Newton, Mass., and a subsidiary in Israel. The company raised Series A funding of $20 million in 2010 and began testing XPOVIO in 2012. Karyopharm now employs more than 300 people and is listed on the NASDAQ stock exchange.

Shacham is particularly bullish on the company’s Israeli operation.

“Most US-based companies will open an office in Europe,” she tells ISRAEL21c. “We chose to move that to Israel instead – for several reasons. First, the quality of the people in Israel is outstanding. They are very well educated, collaborative and they love to tell us what’s wrong. Israeli companies have a very open dialogue with the medical community in Israel, as well, which is key.”

In addition, Israeli business and work culture is “more similar to American culture than European culture,” Shacham says.

And a surprising third reason: “Ben-Gurion is an excellent airport.” Not only does it run efficiently, she says, but it is easy to get to partner hospitals in Europe. “For central and eastern Europe, you have more low-cost flights out of Ben-Gurion than the typical airport in the European Union.”Israel is close in time zone to Europe and the seven-hour difference from the East Coast of the United States is workable.

“I really hope this model will be adopted by other biotech companies,” Shacham says.

Patients interested in joining a clinical trial of XPOVIO – in Israel or elsewhere – can find a full list of testing sites at Karyopharm.