Score one for the trees! After a three-year struggle, last month the Tel Aviv branch of the Society for the Protection of Nature (SPNI) reached an agreement with NTA Metropolitan Mass Transit System to alter the light-rail route planned for Jerusalem Boulevard in Jaffa, so as to preserve 26 ficus trees lining the street.

According to SPNI bloggers Galia Limor-Sagiv and Aya Tager, “The 26 mature trees, between 70 and 100 years old, were slated for destruction, destined to join the dozens of trees that had already been removed along the route of the mass transit system since the [NTA] project was launched in August 2015.”

Israel’s track record with tree-planting is very good, as one of the only nations in the world that entered the 21st century with more trees than it had 100 years before. But its record for tree preservation is less than stellar.

Rapid expansion and urban transport projects, like the Tel Aviv light rail, are transforming the face of cities planned a century ago, and tree removal is considered a necessary part of that change. In August, Globes reported that the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development had changed the criteria for developers, easing the process of tree removal and compensation paid for felled trees.

However, from an urban development perspective, ficus isn’t wholly appropriate for cities. Its gnarled roots are so strong they can penetrate underground infrastructures like sewer pipes, power and telecom cables, and even uproot sidewalks.

And since the arrival in the 1970s of the parasitic Ceratosolen arabicus wasp (the only insect that can pollinate these trees), Israel’s cities have been plagued by the trees’ inedible reddish berries that ripen and fall to the ground, leaving the sidewalks — and the shoe-soles of those passing underneath — encrusted with a gritty jamlike substance. The fruit is also fodder for bats that tend to spit out streaks of berry residue onto building facades.

How did we get into this sticky mess? After all, the Ficus sycomorus, (also known as the sycamore fig or the fig-mulberry) and the fruit-bearing Ficus carica are part of a species that has been cultivated in this region for at least 6,500 years.

Fig trees and sycamores are mentioned in the Jewish and Christian Scriptures. Mulberry and fig trees are mentioned in diaries written between 1812 and 1883 by Sir Moses and Lady Judith Montefiore as they traveled through the Land of Israel.

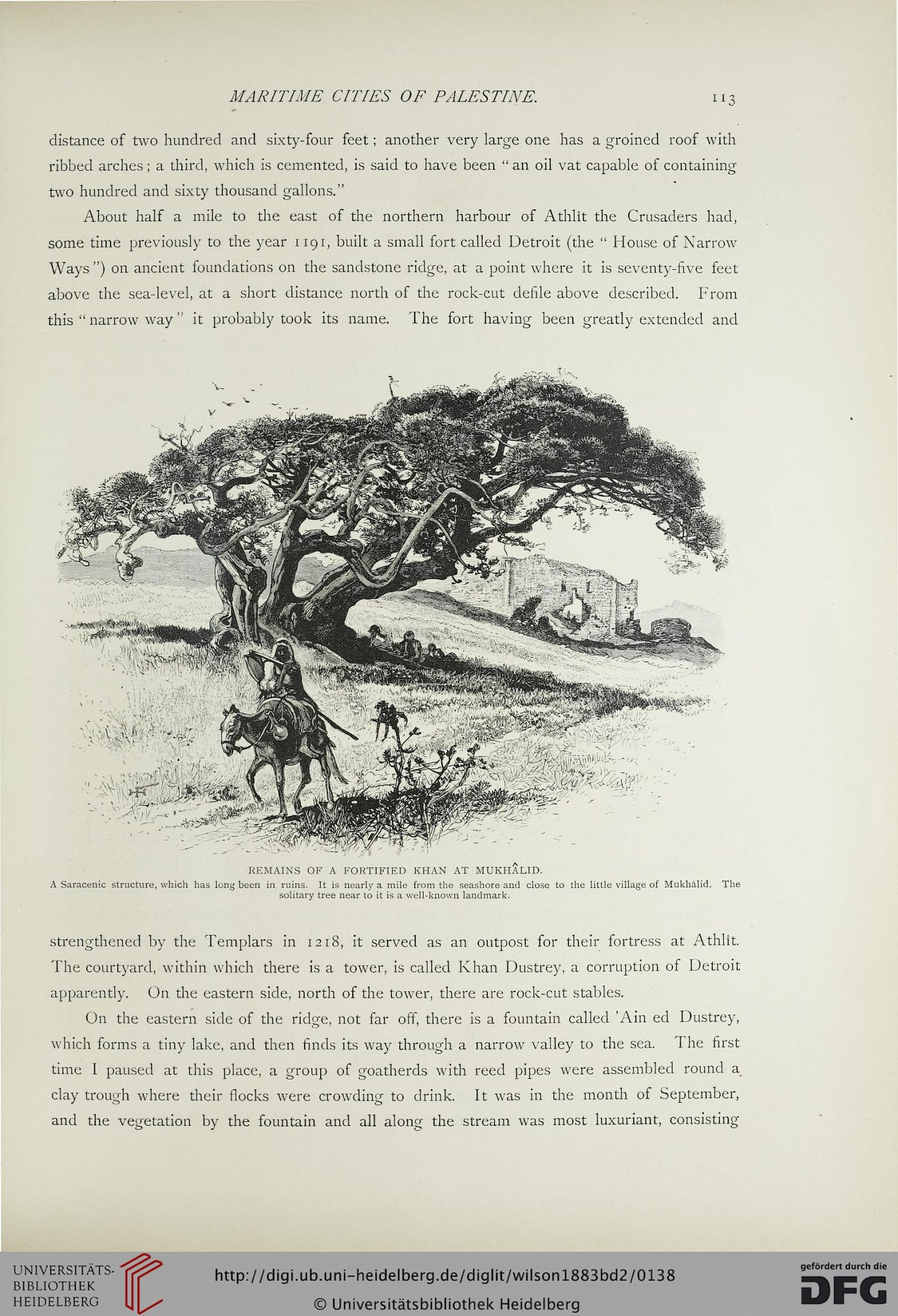

Those trees, along with others native to the Holy Land (such as olive, tamarisk and cypress), were recorded and illustrated in detail in 1881 and 1883 by British Army officer, geographer and archaeologist Major-General Sir Charles W. Wilson in his book Picturesque Palestine: Sinai and Egypt.

Today, there are other ficus subspecies in Israel: Ficus benghalensis (Banyan), Ficus palmata, Ficus religiosa (also known as the Ficus sacra or Bodhi tree under which the Buddha found enlightenment), and the Ficus microcarpa (Indian laurel), Ficus obliqua, Ficus retusa – known colloquially in Hebrew as ficus ha-shderot or “boulevard ficus” – and weeping fig or Ficus benjamina.

These subspecies are not native to the region. They are listed in a report issued jointly by the Ministry of Environmental Protection, Ministry of Agriculture, Nature & Parks Authority and Hebrew University Botanical Gardens entitled “Israel’s Least Wanted Alien Ornamental Plant Species.”

How did these troublesome aliens get here?

According to the “Survey of Mature Trees (1999-2005)” conducted by the Ministry of Environmental Protection, Ministry of Agriculture, Nature & Parks Authority, KKL-JNF and the Horticultural & Landscape Association in Israel, the first Ficus benghalensis was planted in 1888 by Carl Netter, founder and first headmaster of the renowned Mikveh Yisrael agricultural school, who also successfully cultivated the E. camaldulensis strain of eucalyptus – still the most common eucalyptus species in Israel.

The survey states, “The ficus of Mikveh was the source of the propagation material for other trees planted in Israel.”

Which brings us back to Jaffa and Jerusalem Boulevard.

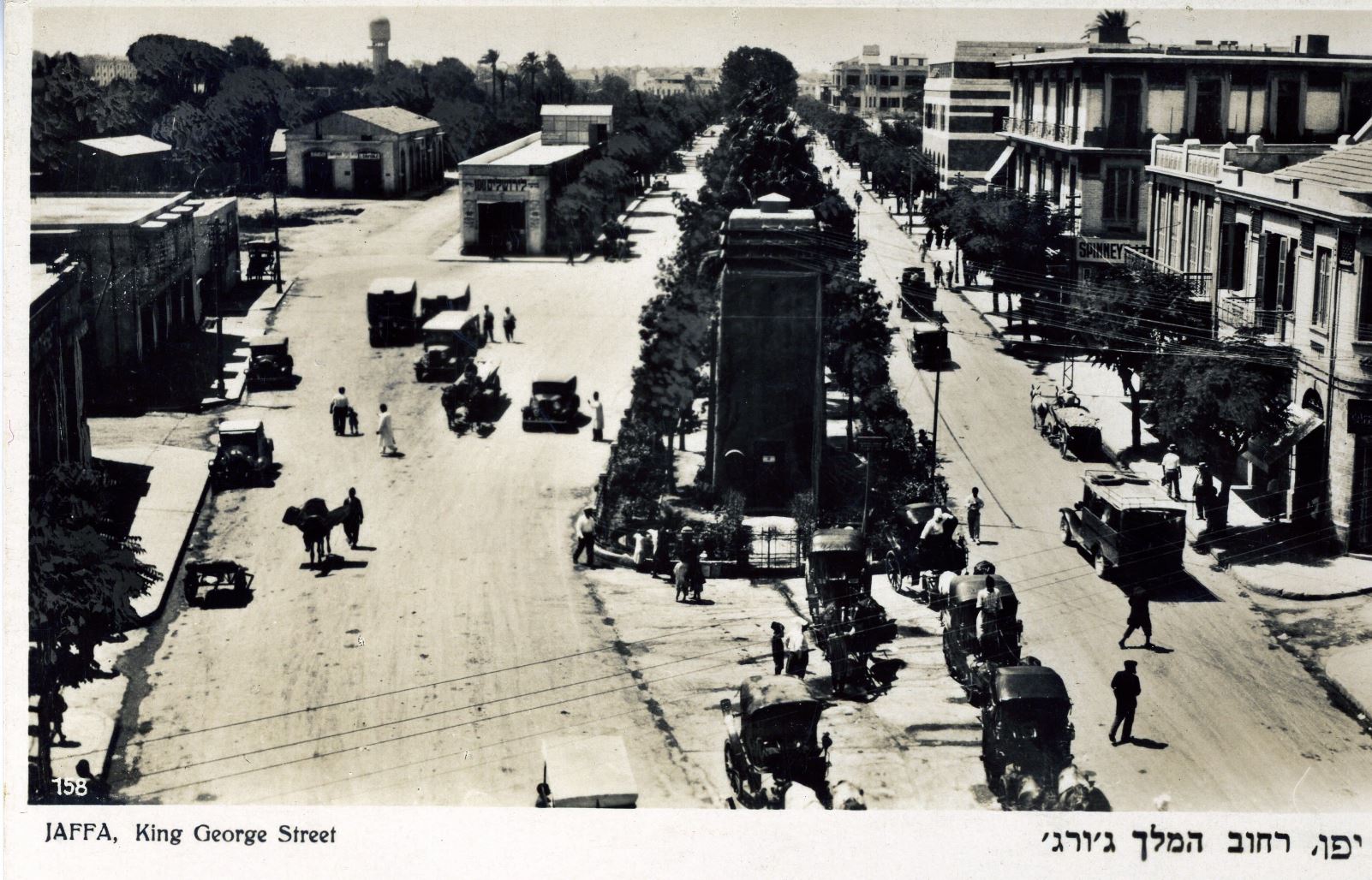

In 1914, the newly appointed Governor of Jaffa, Hassan Bey, initiated development activities including construction of a modern avenue reaching from the sea to the orange groves at the eastern end of the city.

In 1915, Turkish Sultan Mehmed V appointed engineer Gedalyahu Wilbushevitz as the director of public works in Jaffa, in which capacity he supervised the construction of a boulevard lined with Washingtonia palm trees and ficus supplied and planted by none other than students from Mikveh Yisrael.

The “Survey of Mature Trees” notes that Ficus microcarpa was planted on the Jaffa boulevard in 1916.

Under Ottoman rule, the boulevard was named after the governor of Syria and Palestine, Ahmed Djemal Pasha (also known Jamal Pasha the Bloodthirsty). With the advent of the British Mandate in 1917, the name was changed to King George V Boulevard.

In 1922, the Jaffa Electric Company began construction of Tel Aviv’s first electric power station and in 1923, a secondary power station was erected on the boulevard, designed by architect Richard Kauffmann in modernist style.

The street continued to develop into a commercial and cultural center, with theaters, cinemas, public buildings and shops. After the War of Independence, Tel Aviv and Jaffa were merged into one city in 1949 and the street renamed Jerusalem Boulevard.

Around the country, non-native ficus trees continued to be planted as towns developed from the 1920s through the 1940s. They provided much-needed shade and, until the 1970s, shed only small greenish pellets that bothered no one. How the wasps entered the Israeli ecosystem remains a mystery; one theory is that they were transported inside figs imported from Turkey.

Amazingly, the Ficus sycomorus depicted near the ancient fortress in Wilson’s engravings was identified, still standing in a small public park on Mintz Street in Netanya. As a tree of tropical origin, ficus don’t produce annual rings so it is difficult to ascertain its age. The Survey of Mature Trees estimates it at between 600 and 1,200 years old.

Over the decades Carl Netter’s Ficus benghalensis and its immense aerial roots, so thick they look like tree trunks themselves, has become identified with the school’s illustrious history.

Jaffa was neglected for many decades and Jerusalem Boulevard fell into disrepair. In 2000, a renewal plan incorporated, among other things, new pavements, bicycle paths, sewer infrastructure and the light rail line to run along Jerusalem Boulevard.

One sad victim of progress was the secondary power station. In an essay about the structure, music producer and Tel Aviv history buff Danny Recht writes that despite its historical and architectural importance, “…the company developing light rail project did not want to bear the costs of preservation. Thus, without any public discussion, the company initiated, in cooperation with the Municipality, a demolition that took place on a rainy and cold winter night (and without any curious onlookers) on one of the last nights of December 2007.”

Given the threat of such actions, the SPNI’s Tel Aviv Branch initiated a campaign that called for an open discussion of the light-rail plan with all relevant parties, including the Tel Aviv municipality, residents, professional planners, environmental organizations, and others. An alternative plan was drafted to save the trees while allowing rail construction to continue.

When the light rail’s Red Line opens in around 2021, its passengers will enjoy viewing — and being pelted by — those 26 ficus trees.

![Elections 1977 – Likud posters] In 1977, Menahem Begin led an election upset as Israel’s first non-Labor prime minister. Credit: GPO Elections 1977 – Likud posters] In 1977, Menahem Begin led an election upset as Israel’s first non-Labor prime minister. Credit: GPO](https://static.israel21c.org/www/uploads/2019/09/Elections_1977___Likud_posters_-_GPO-768x432.jpg)