It’s hard not to notice the abundance of hamsas on display when walking through the markets in Israel. The ancient hand-shaped symbol appears on pendants, tableware, clothing and religious items, and on metal and wooden objects of all kinds.

Yet the hamsa (also spelled “khamsa”) wasn’t always this prevalent in Israel. Since its origins in the Middle East and North Africa and its immigration to Israel along with Jews from the region, the hamsa has gone through a cultural evolution.

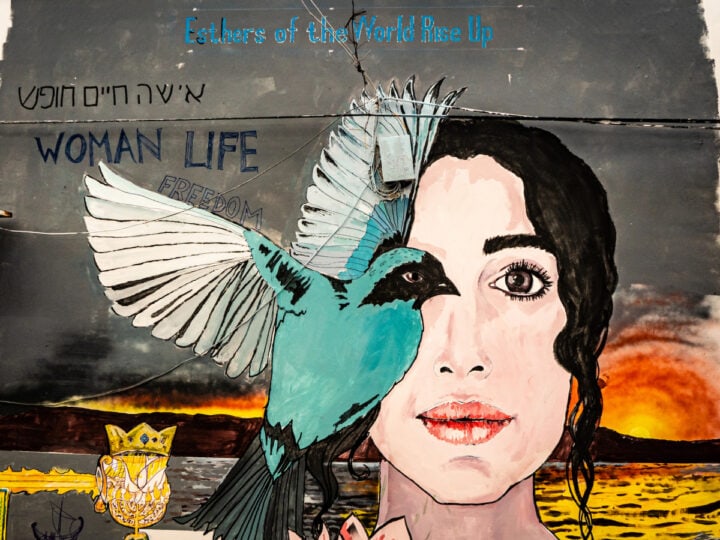

Once a religious symbol rooted in superstition, today it is a trendy motif appreciated by people of all faiths and backgrounds.

The new exhibition “Khamsa, Khamsa, Khamsa” at Jerusalem’s Museum for Islamic Art aims to highlight the hamsa’s integral role in contemporary Israeli culture and its growing, widespread appeal.

Curators Shirat-Miriam (Mimi) Shamir and Ido Noy explain that unlike other exhibitions that have focused on the historical significance of the hamsa, this exhibition examines the place of the hamsa in society today.

“In our exhibition we have Israelis, Arabs, Jews, Muslims, Christians, Haredim, Bedouins, and secular people; people from Haifa, Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, the North and the South,” Shamir told ISRAEL21c. “We captured all of the ‘tribes’ of Israel. It represents the whole community and everyone can connect.”

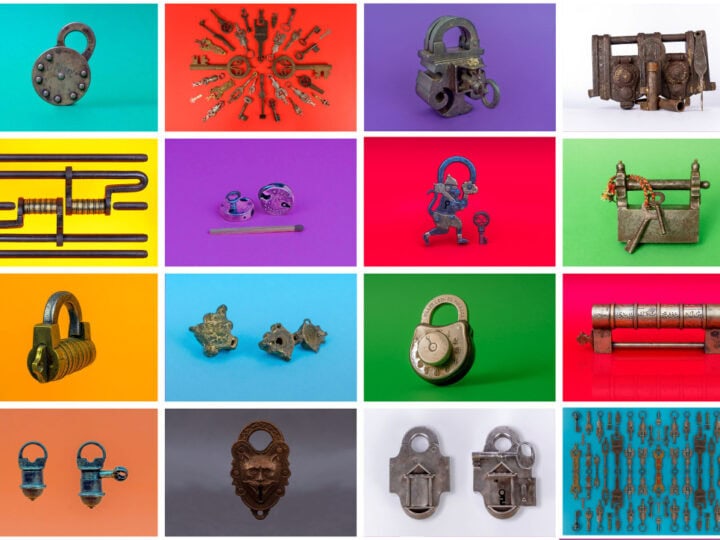

On display are 555 hamsas created and collected from 2017 to 2018. The exhibition title and number of works displayed echo the common Israeli phrase “hamsa, hamsa, hamsa” meant to ward off bad luck and the evil eye with the five-fingered hand.

Hamsas in Judaism and Islam

The power associated with the hamsa comes from the many mystical and religious meanings associated with the hand and the number five in Judaism and Islam, making it a symbol and a talisman in both religions.

Known in the Islamic world as the hand of Fatima, the daughter of Muhammed, the amulet has been used since as early as the seventh century. As it became more popular, the symbol made its way into Jewish communities in Arab and Islamic countries.

Although Sephardic (Middle Eastern and North African) Jews immigrated to Israel in the 1940s and ’50s, the hamsa didn’t make its mark in Israel until a few decades later.

“I went into the archive to try to find photographs of [Sephardic] women wearing hamsas and I couldn’t find any because they would try to hide it. They put it inside their shirts,” explains Shamir, who holds a doctorate in Jewish art from the Hebrew University.

She pinpoints the 1970s and ’80s as a hamsa turning point, when people brought out the symbol and used it not just to bring luck and good health but also “to celebrate a bar mitzvah, to buy as gifts, to hang on the refrigerator.”

Hamsas of today

The exhibition curated by Shamir and Noy highlights the many forms of the hamsa that can be found in Israel today, including works made especially for the exhibition by top Israeli artists, both Jewish and Arab.

One section of the gallery, comprised of hundreds of hamsas purchased from markets around Israel, focuses on the “commercial” hamsa. Displayed on an illuminated wall, hamsas engraved with expressions in Hebrew, Arabic, Spanish, Russian, German and English are hung side by side, along with sequined hamsas, hamsa keychains, a hamsa iPhone case and more.

Several hamsas with images of Jesus, the Christian cross, and compartments for holy water and soil from Bethlehem show the popularity of the hamsa as a souvenir for Christian tourists.

Another part of the exhibition showcases works by prominent painters, sculptors, industrial designers, jewelry designers, and other artists invited by the museum to create modern interpretations of the hamsa.

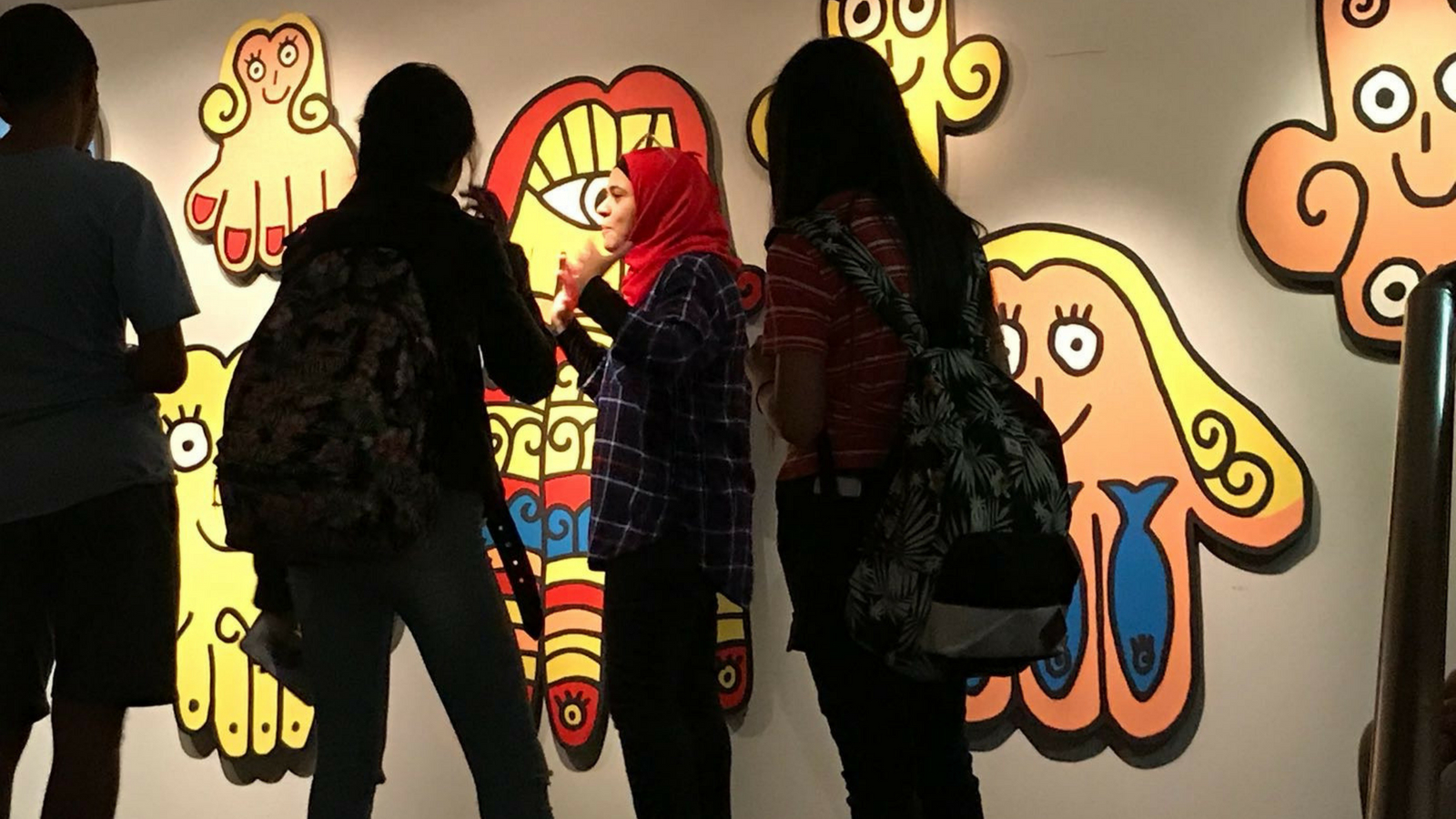

Ken Goldman’s Huggable Hamsas serve as a friendly, colorful welcome to the exhibition, allowing visitors to actually embrace and interact with the giant, fluffy amulet.

In a video work by Fatma Shanan, a 16th century Ottoman prayer rug is presented as the artist’s hamsa – her source of protection, health and prosperity.

Zenab Garbia’s embroidered ceramic hamsa touches upon her identity as a Bedouin woman. In Bedouin culture, embroidery is typically passed down from mother to daughter.

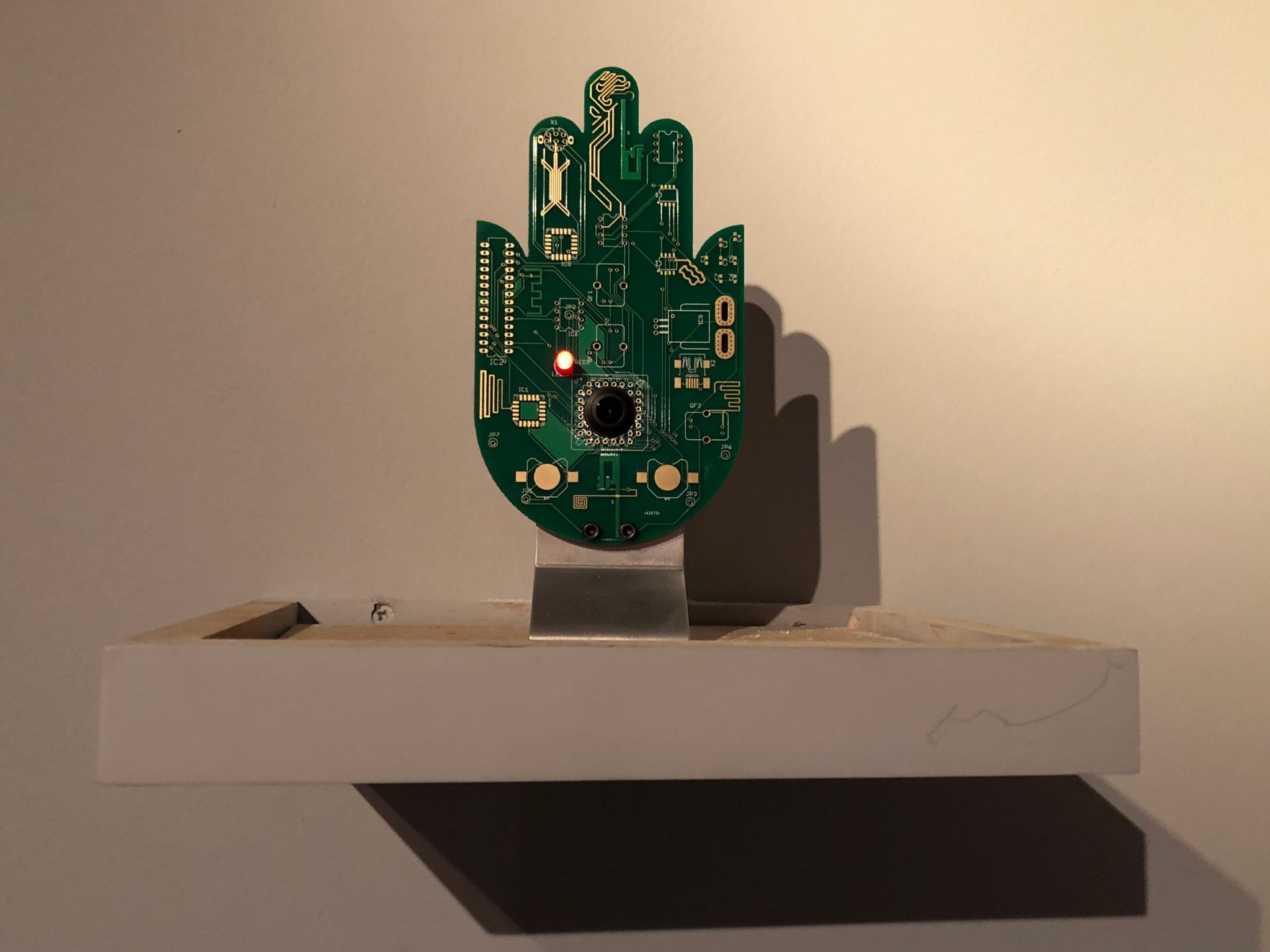

Several artists created digital hamsas. Rory Hooper’s “Hamsa-cam,” made from a printed circuit board, features an HD surveillance camera in the center of the hand, taking the place of the evil eye.

Andi Arnowitz’s video installation invites visitors to tag photographs of their hands on Instagram using the hashtag #onemillionhamsas. The project is designed to create a sense of belonging and unity across any religion and culture.

Less than a month since the exhibition opened, Shamir noticed an increase in the diversity of people visiting the museum as well as an increase in visitors overall. She’s noted tour groups speaking French, Arabic, Hebrew and English. “I think it has been the most popular exhibition yet.”

For more information, click here.