Researchers in Israel report they have discovered a molecule in newborn hearts that appears to control the process of renewing heart muscle.

When injected into adult mouse hearts injured by heart attacks, this molecule, called Agrin, seems to “unlock” that renewal process and enable heart muscle repair – something never seen in human heart tissue outside of the womb.

These findings, published June 5 in Nature, point to new directions for research on restoring the function of damaged hearts. Heart disease is the leading cause of death worldwide.

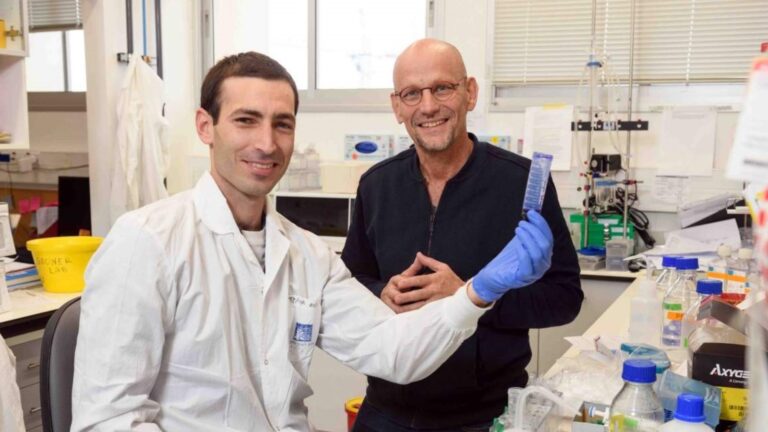

The healing process following a human heart attack is long and inefficient, explained Prof. Eldad Tzahor of the Weizmann Institute of Science, who led the study together with doctoral student Elad Bassat, research student Alex Genzelinakh and other Weizmann molecular cell biologists.

Once damaged, muscle cells called cardiomyocytes are replaced by scar tissue, which cannot pump blood and therefore place a burden on the remaining cardiomyocytes.

Heart regeneration can happen in utero for humans, but some vertebrates retain this ability after they’re born. Mice hearts can regenerate only for the first week of life. Those seven days gave the Israelis an opportunity to explore the cues that promote heart regeneration.

Finding the protein

Tzahor and Bassat zeroed in on the surrounding supportive tissue known as the extracellular matrix (ECM) through which cell-to-cell messages are passed or stored. When bits of ECM from newborn and week-old mice were added to cardiac cells in culture, the younger ECM caused cardiomyocytes to proliferate.

Agrin, a protein present in ECM, already was known to help regulate the signals passed from nerves to muscles. In mouse hearts, levels of this molecule drop over the first seven days of life, suggesting a possible role in heart regeneration. When the researchers added Agrin to cell cultures, they noted that it caused the cells to divide.

Next, they found that mouse hearts were almost completely healed and fully functional following a single injection of Agrin. Although this recovery process took more than a month, the scar tissue was dramatically reduced, replaced by living heart tissue that restored the heart’s pumping function.

Setting the chain in motion

Tzahor speculates that in addition to causing a certain amount of direct cardiomyocyte renewal, Agrin somehow affects the body’s inflammatory and immune responses to a heart attack, as well as the pathways involved in suppressing the fibrosis, or scarring, which leads to heart failure.

The length of the recovery process, however, is still a mystery, as Agrin disappears from the body within a few days of the injection.

“Clearly this molecule sets a chain of events in motion,” Tzahor said. “We discovered that it attaches to a previously unstudied receptor on the heart muscle cells, and this binding takes the cells back to a slightly less mature state – closer to that of the embryo – and releases signals that may, among other things, initiate cell division.”

The team then proved that Agrin has a similar effect on human heart cells grown in culture.

Members of Tzahor’s team have started pre-clinical studies in larger animals in Germany in collaboration with Dr. Christian Kupatt of the Technical University of Munich to determine the effect of Agrin on cardiac repair.

Several research groups took part in various stages of the research: Prof. Shenhav Cohen of the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology and her PhD student Yara Eid; Prof. Nenad Bursac of Duke University, North Carolina; James F. Martin of Baylor College of Medicine in Texas; members of the Nancy and Stephen Grand Israel National Center for Personalized Medicine at the Weizmann Institute; and Prof. Irit Sagi of the Weizmann Institute’s Biological Regulation Department.

Tzahor’s research is supported by the Yad Abraham Research Center for Cancer Diagnostics and Therapy, which he heads; the Henry Krenter Institute for Biomedical Imaging and Genomics; the Daniel S. Shapiro Cardiovascular Research Fund; and the European Research Council.