Less than a year into its planned three-year study of the planet Jupiter, NASA’s Juno research spacecraft already has revealed or confirmed facts that the Juno Science Team – including Yohai Kaspi of Israel’s Weizmann Institute of Science – could only guess at previously.

“We knew, going in, that Jupiter would throw us some curves,” said Scott Bolton, Juno principal investigator. “But now that we are here we are finding that Jupiter can throw the heat, as well as knuckleballs and sliders. There is so much going on here that we didn’t expect that we have had to take a step back and begin to rethink of this as a whole new Jupiter.”

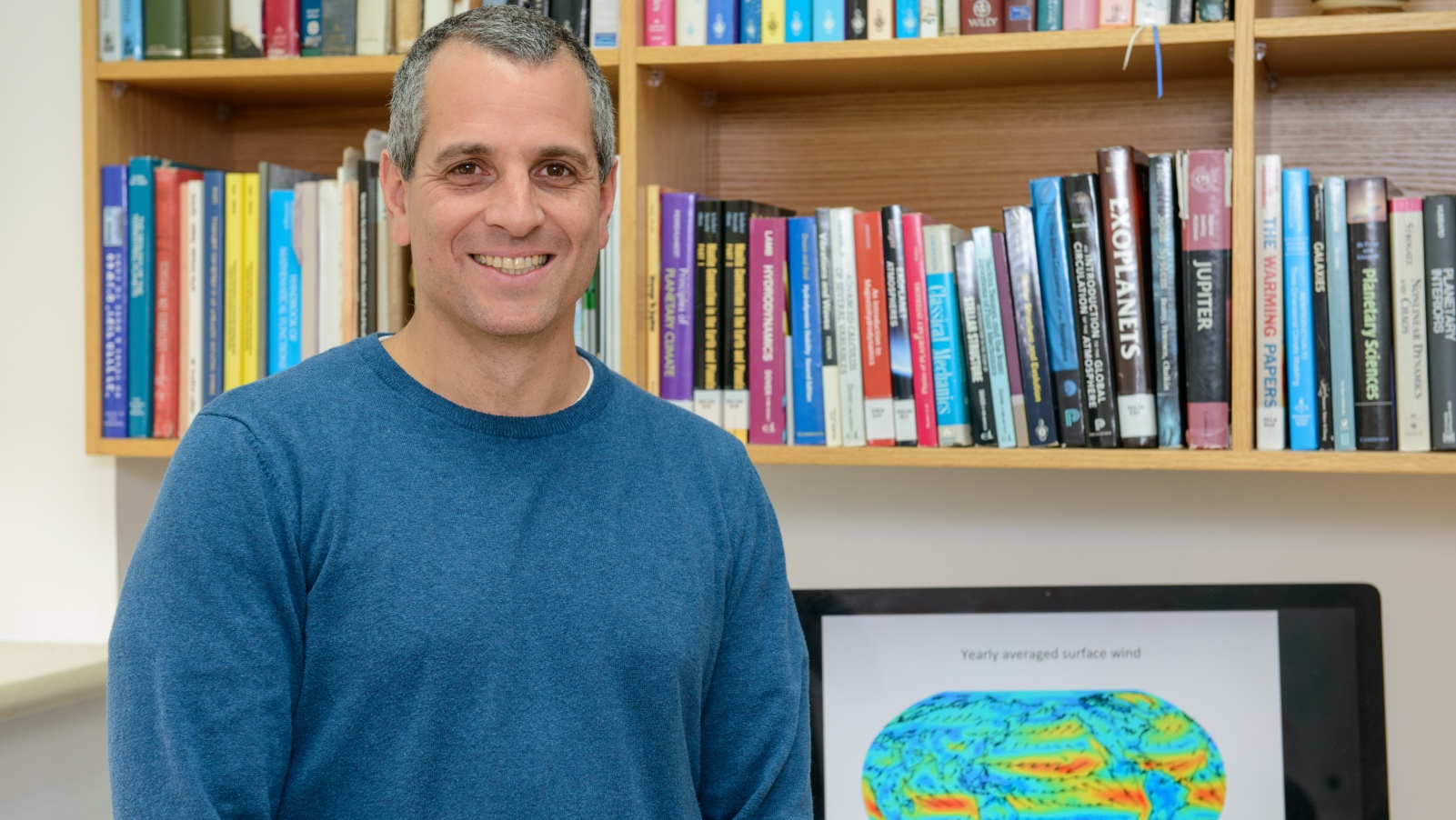

Talking with ISRAEL21c from the NASA Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, Texas, where the team meets after each 53-day orbit to analyze data transmitted from the Juno Mission, Kaspi shared highlights of the research published Friday in Science and accompanied by 44 detailed papers in Geophysical Research Letters.

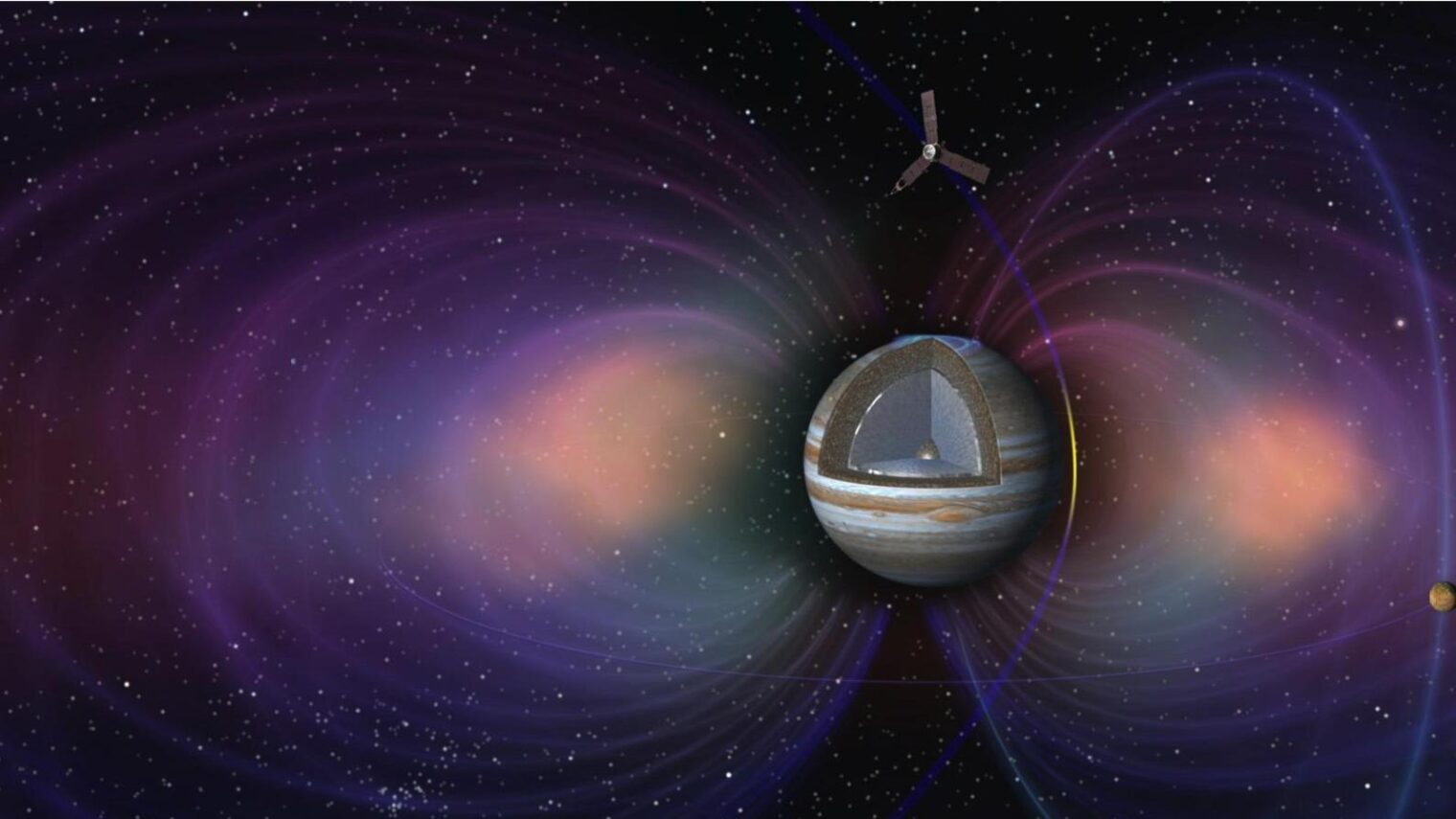

Fact #1: Jupiter’s core is more packed with heavy elements and bigger than scientists thought, measuring between 7 and 25 Earth masses as opposed to the previously assumed 0 to 14, though the new understanding is that it is more diluted.

Kaspi says this fact has implications for our understanding of how the gassy planet was formed. Jupiter, the biggest and oldest planet in the solar system, is equal to more than 300 Earth masses and contains half the mass of the solar system excluding the sun. A better understanding of Jupiter’s core is a central clue to its beginnings.

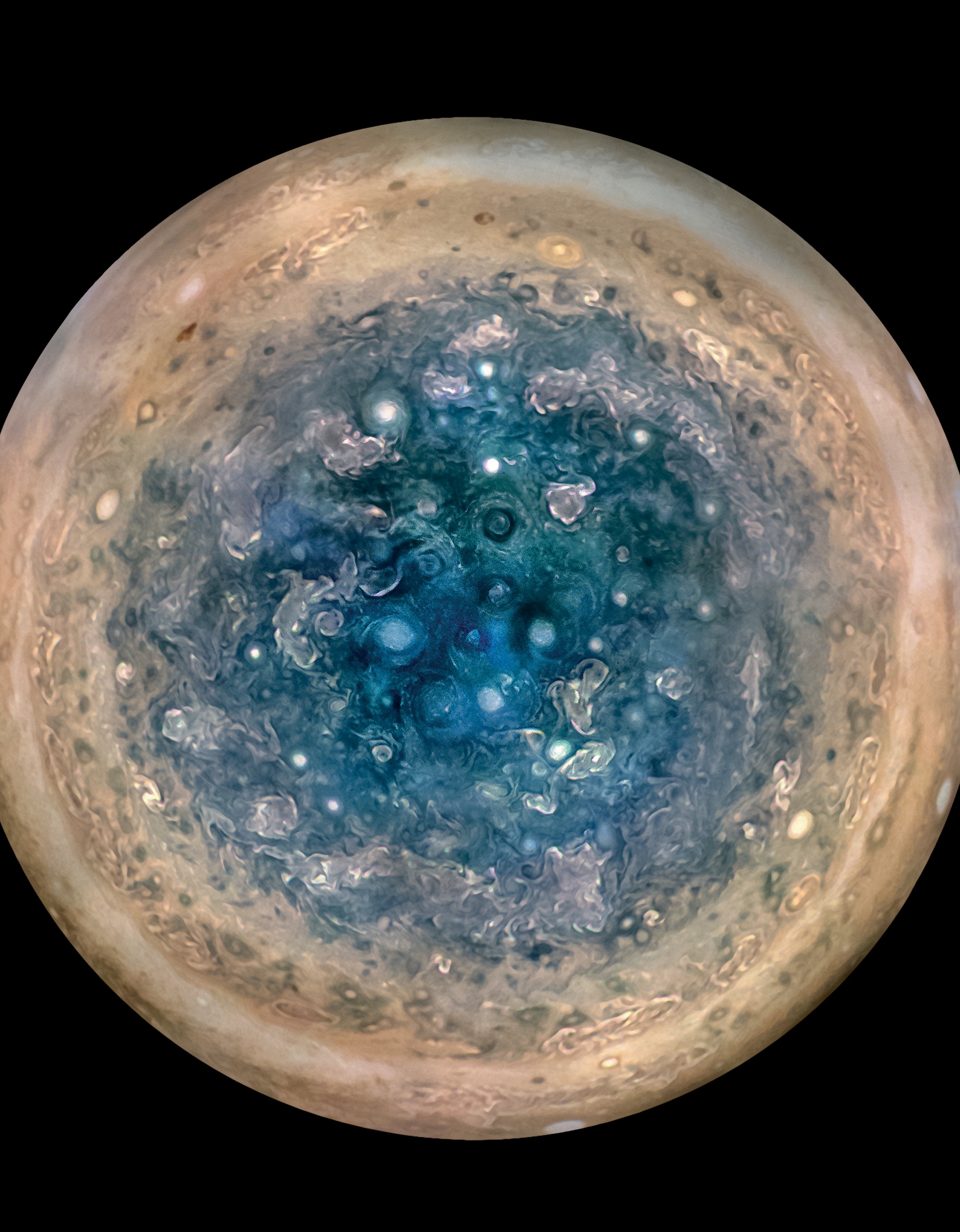

Fact #2: Jupiter’s atmosphere has a different ammonia distribution than expected. “The distribution of gases is different than we thought and there is a very strong plume near the equator from hundreds of kilometers deep in the atmosphere,” says Kaspi.

Fact #3: Jupiter’s magnetic field is twice as strong as scientists thought previously — about 10 times stronger than the strongest magnetic field found on Earth — and more irregular in shape. “Jupiter has an enormous magnetic field because it’s rotating fast and has a lot of charged particles,” explains Kaspi.

Fact #4: The motion of Jupiter’s gases significantly affects its gravity field, something scientists suspected but could not prove before Juno enabled them to measure the gravity field many more times accurately than ever before.

Kaspi devised the tools for analyzing Juno’s measurements of Jupiter’s gravity.

“All we knew so far was from looking at the outside of the planet,” he tells ISRAEL21c. “Juno is the first spacecraft not just taking pictures but using a suite of nine instruments to look inside the planet and study its internal processes.”

100,000 kilometers per hour

Juno launched on August 5, 2011, from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida. Kaspi and Weizmann Institute staff scientist Eli Galanti were among scientists and engineers gathered at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, to watch Juno arrive in orbit around Jupiter on July 4, 2016.

The spacecraft soars low over the planet’s cloud tops, as close as about 2,100 miles (3,400 kilometers). During these flybys, Juno probes beneath the obscuring cloud cover of Jupiter and studies its auroras to learn more about the planet’s origins, structure, atmosphere and magnetosphere.

“We just completed our sixth flyby. When we zoom in, we go pole to pole in about two hours, traveling 100,000 kilometers an hour,” says Kaspi, 43.

“For the first time, we have an opportunity to study the flows beneath the thick clouds we see covering Jupiter.”

Kaspi has been involved in the mission since 2008, three years after the Juno project was approved by NASA. He is one of six non-Americans on the 43-person Juno Science Team.

After four years in the Israeli military, Kaspi earned an undergraduate degree in physics and math at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, a master’s degree in physics at the Weizmann Institute in Rehovot, and a doctorate in atmospheric dynamics at MIT. He was a postdoc at Caltech and came back to Weizmann six years ago as an assistant professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences.

His research is supported by the Israeli Ministry of Science Helen Kimmel Center for Planetary Science.

For more information, click here.