When the president of the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology asked Prof. Hossam Haick to teach the institute’s first massive open online course (MOOC) – in English and in Arabic — the award-winning Israeli-Arab nanotechnology expert agreed immediately.

Then he found out how difficult a task he had accepted. One of the hardest aspects was translating all the cutting-edge technical terms into a common Arabic dialect.

“One of my main weaknesses is that I say ‘yes’ before I think how to do it,” Haick tells ISRAEL21c. “The idea of teaching thousands of people across the world seemed very nice to me. I didn’t know the challenges. It took nine months to put it all together.”

The 10-week course, “Nanotechnology and Nanosensors”, begins March 2 on the Coursera platform.

About 4,800 people have signed up for the Arabic MOOC. They include academicians, researchers, businesspeople and just plain curious folks from Egypt, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Iraq, Kuwait, Algeria, Morocco, Sudan, Tunisia, Yemen, the United Arab Emirates and the West Bank. (Registrants from Iran will take the English version.)

Haick, 38, was surprised to encounter skepticism about his credentials from some would-be students.

“Many people thought there was no chance an Arabic scientist could be teaching an Arabic course in a Jewish university, and many suspected I was a Jew pretending to be an Arab,” he says.

“I got many of these questions and inquiries, but in the end we got 4,800 registrations, which is a very huge number considering there are 200 million people in the Arab world. We got almost 26,000 registrations for the English version, out of about seven billion people overall.

“So you can see the registration rate for the Arabic course is much higher, and if I could give this course in an Arabic country, I think the number would be a little higher. This indicates the extraordinary eagerness of the young Arabic-speaking generation to learn futuristic science and technology,” says Haick, a Ben-Gurion University and Technion alumnus who teaches four courses and researches topics at the crossroads of nanotechnology and medicine.

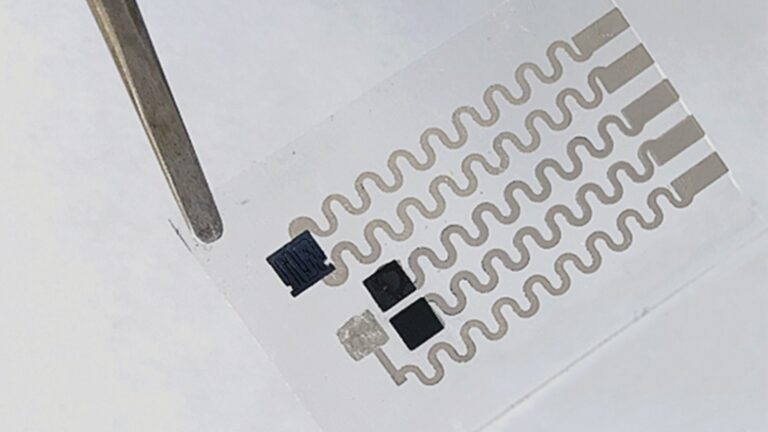

He recently made headlines with his new nanosensors that may one day be used to create electronic “skin” that senses touch, heat and humidity. And he continues to work with the Technion’s Alfred Mann Institute to develop his NaNose for detecting cancer and kidney disease from breath analysis.

Science for peace

Haick tells ISRAEL21c that he first prepared the MOOC in English. Though he teaches in Hebrew, he always uses English for the main technical terminology for which there is no equivalent.

But he learned that some Arab countries require every foreign phrase to be translated. Therefore, he faced the challenge of not only translating the course and related written materials into a traditional Arabic dialect that could be fairly well understood in all the countries, but also finding Arabic words to describe technical terms. The Arabic Language Academy assisted him.

However, since both he and his students are unfamiliar with the translated phrases, he decided to state the Arabic term and then the English translation in the video lectures, which are titled “Introduction to Nanotechnology,” “Introduction to Sensors Science and Technology,” “Nanowire-based Sensors,” “Carbon Nanotube-based Sensors” and “Arrays of Nanomaterial-based Sensors.”

He says he has no regrets about taking so much time from his professional and personal obligations and community volunteering to prepare the lectures, activities and 200-page source book.

“My message is that there are no boundaries between peoples but only between countries. We all have to find the way to fly over the boundaries and connect with each other because this is the way to make peace,” he says.

In an interview with ISRAEL21c in 2011, he had stated that borders between Arabs and Jews are non-existent at the Technion. Now, he adds, “Science and technology is a pretty good way to facilitate peace between people, and this [in turn] will bring peace between countries.”

He is especially gratified to note that of the Arabic-speaking registrants, only 45 percent are students. The rest are business people (19%), scientists (15%), professors and others.

“The dissemination of the material not only to the academy but to industry and beyond, hopefully will increase the effectiveness of the message that I, and the Technion, want to bring to the people,” says Haick, a native of Nazareth who was named one of the 10 Most Promising Young Israeli Scientists by Calcalist in 2010.