It was an ignoble ending to what was one of the most buzzed-about startups in Israeli history. On May 26, 2013, Israeli electric car network pioneer Better Place declared bankruptcy.

Yet now, even a decade later, Better Place’s impact is still being felt. One could even say that Better Place put electrification of vehicles onto the automotive industry’s agenda.

Would there be a Tesla if Better Place hadn’t come first?

Would GM, Ford, Mercedes and virtually every other automaker be committing to phasing out production of ICE (internal combustion engine) vehicles, in many cases as early as 2030 or 2035, if there had never been a Better Place?

And what would have happened if Better Place, against all odds, had succeeded?

“The key idea behind Better Place, when it launched in 2007, was that it will be 10 years until there are batteries good and cheap enough for mass adoption, but we have a formula to speed up mass adoption right now,” Mike Granoff, then Better Place’s head of oil independence policies, explained.

That formula involved swapping batteries in a matter of minutes via a robotic “switch station” rather than plugging in for an hour or more to charge.

“People tell me all the time, ‘You guys were ahead of your time,’” Granoff said.

“No, we weren’t. Our business model wasn’t designed to ride a wave of EV adoption as we see today among automakers. It was designed to generate that wave by making EVs work for ordinary consumers even with immature battery technology. Had it succeeded, we’d be in a world where 50% of all cars would be EVs, not 10% as we have now. “

With the right execution, Granoff concluded, “Better Place would have dwarfed Tesla in impact.”

Victim of its own success

The Tesla-Better Place rivalry is not mentioned much today, since one company joined the ranks of the most highly valued in the world while the other went kaput.

But when both companies were still finding their footing, it was Better Place that was getting all the hype – and nearly a billion dollars of investment – while Elon Musk was ironically “bragging” that he was so broke he had to sleep on friends’ couches.

Ultimately, Tesla received a bailout from the US government, which allowed it to get past the lean times. Better Place, meanwhile, was a victim of its own success.

“We raised too much money too soon,” Quin Garcia, who built the first electric prototype for Better Place, told ISRAEL21c. “Raising too much money causes startups to achieve an inflated valuation and to spend money differently than if they were starving more.”

While one can point accusatory fingers at the management, the board or the business model, the company simply ran out of money and was unable to raise more.

Calming range anxiety

Better Place burst out of the gate with an innovative approach to the biggest problem with electric cars in 2007: range anxiety.

Even the best batteries at the time could only provide 100 or so miles per six- to seven-hour overnight charge.

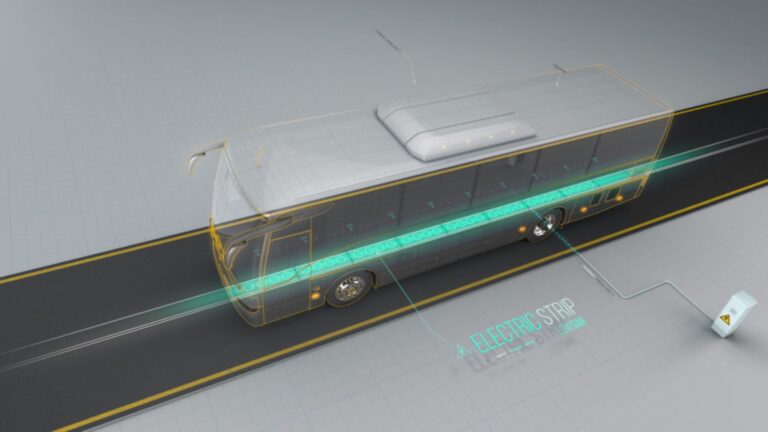

So, Better Place built 42 switching stations across Israel.

You’d pull into what looked like a high-tech car wash, where your car would be raised on a platform and a robot would unscrew a panel, remove the spent battery and replace it with a fresh one.

All that in five minutes – essentially the same as filling up with gas.

Battery swap made sense in 2007 and, to a certain extent, it still does. For most EV drivers, Granoff said,

it makes no sense to spend tens of thousands of dollars for a bigger battery that will give you longer range but that you’ll only use once or twice a year.

That has made EVs with big batteries, like those from Tesla, unaffordable for most. But by separating the battery from the car (it was Better Place that owned the battery, not the driver), the economics started to work in consumers’ favor.

Swap it out

Battery swap hasn’t disappeared entirely. Automaker NIO is building mobile battery swap stations for its cars in China. San Francisco-based Ample is pursuing a similar strategy in the US.

But battery swapping has caught on most of all in the micro-mobility sector.

Taiwan’s Gogoro has built hundreds of battery swap “vending machines” allowing electric scooter owners to swap their batteries by hand. India’s Battery Smart is taking a similar approach for scooters and autorickshaws, some 35% of which are now electric, Pulkit Khurana, the company’s CEO, says.

Even Tesla briefly trialed a battery swap model.

A month after Better Place went belly-up, Musk announced that its high-end models would have a switchable battery option. Musk even demonstrated a 90-second battery swap on stage and built a prototype switching station between Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Drivers gave the idea a lukewarm response, and Musk told shareholders and investors in 2015 that “Clearly, it’s not very popular.”

Better batteries

Today, though, it doesn’t much matter – at least for passenger EVs.

That’s because battery chemistry is getting better.

All manner of alternatives to the current standard lithium-ion batteries are proposed (for some reason, they all seem to begin with the letter “S” – sodium, sulfur, salt, silicon and solid-state) that give better performance, longer range and faster charging.

Israeli startup StoreDot, which is currently adding silicon to its battery mix and plans to move to solid-state, promises that just five minutes of being plugged into a charger can grant an EV an additional 100 miles of range.

US-based Sila, which also uses silicon in its battery chemistry, has raised a billion dollars and signed Mercedes as a client.

Ford is offering two battery types – the standard lithium-ion and lithium-ion phosphate which, while it offers a slightly shorter range per charge, is also 30% to 40% cheaper than standard lithium-ion chemistry.

Is this the development, rather than switchable batteries, that will bring EVs to the masses?

Moving on

Meanwhile, former Better Place executives can be found at mobility startups, established companies such as Tesla, Uber and General Motors, and investment firms in both Israel and Silicon Valley.

- Mike Granoff now heads Tel Aviv- and New York-based Maniv Mobility, which invests exclusively in mobility startups.

- Quin Garcia is doing the same from Silicon Valley with his Autotech Ventures.

- Former Better Place CTO Barak Hershkovitz is the executive director of software- defined vehicles, energy and connected mobility services at GM’s Israeli operations.

- Avi Jacoby, Better Place’s former COO, is now the CEO of Fabric, an Israeli startup aiming to revolutionize online fulfillment processes.

- Jelle Vastert joined Tesla and managed its fast charge deployment in Europe.

- Jeff Miller led autonomous vehicle business development at Uber.

- Carlo Tursi also went to Uber and ran its operations in Italy for several years. He is now running an eVTOL (electric vertical take-off and landing) airport infrastructure startup.

Even Better Place’s charismatic founder and CEO Shai Agassi, who was fired six months before the company declared bankruptcy, landed on his feet; he’s now chairman of Makalu Optics, which builds lidar systems for autonomous vehicles, drones and robots.

“There were 500 mobility startups formed in the years after Better Place,” Mike Granoff pointed out. “I’d like to think we inspired some of them.”

Saul Singer, co-author of “Start-up Nation,” isn’t convinced.

“Is there a ‘Better Place mafia’ like there was a ‘PayPal mafia?’” Singer wondered, referring to the exodus of influential rainmakers from a single company – PayPal – into the greater tech ecosystem. Elon Musk of Tesla, SpaceX and now Twitter; Reid Hoffman who co-founded Netflix; and billionaire investor Peter Thiel are among the online payment service’s most illustrious alumni.

A more appropriate parallel – and one that’s closer to home – would be the Lavi project.

The Lavi was Israel’s attempt at building its own warplane to compete with the American-made F-16. The program was shut down in 1987, but the 5,000 scientists and engineers who had been working on the state-of-the-art plane were now free to jumpstart the country’s high-tech boom in the 1990s. Many former Lavi employees were re-employed by the Arrow anti-ballistic missile program. Others helped Israel launch its first satellite into space in 1988.

“Better Place, however, may not have been big enough to produce a Lavi effect,” Singer speculated.

Dan Cohen, who served as Better Place’s CEO in 2013, disagreed.

“It is absolutely fair to say that Better Place contributed in creating the attention and attraction for young and more experienced talent to invest and develop the sector,” he says. Moreover, “the fact that so many people are still following the Better Place story a decade after it shut down is a testament to its impact.”

One area where Better Place’s crash clearly didn’t help was adoption of EVs by local consumers – it’s taken most of the last decade for Israelis to get over the Better Place debacle.

But the curse seems to finally have been broken: In the first quarter of 2023, nearly 20% of new car sales in Israel were electric.

The Better Place story, despite its crash ending, also fits well into the Israeli narrative.

The collapse of Better Place is actually “a good example of how Israelis have a tolerance for failures,” Singer told me for Totaled, the book I wrote about the rise and fall of Better Place. “We don’t hide them. We get up, brush ourselves off and do the next thing.”

That’s echoed in the letter Granoff sent to investors when the bankruptcy was announced.

“I am sorry we were not able to bring the company to the glorious success that it deserved, but I have no regrets for having tried.”

RIP Better Place. Long live electric cars.