It’s not unusual for the new breed of rock-star chefs to bring out glossy cookbooks once their careers take off. Others leave nothing behind and vanish when their once-hyped restaurants shutter.

Then there’s a third group of chefs who write cookbooks only once they have a legacy to share. Jerusalem chef Moshe Basson belongs to this esteemed group.

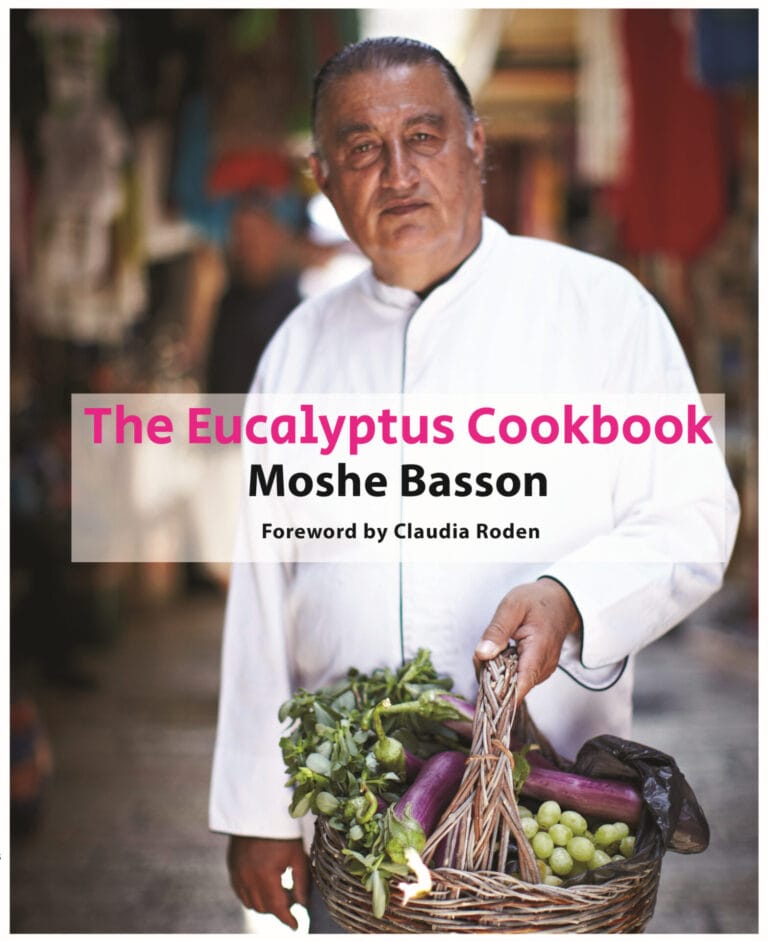

The Eucalyptus Cookbook comes after decades of serving a devoted following of local and foreign diners at his restaurant located across from the Old City walls in Jerusalem’s Artist Quarter (Hutzot HaYotzer).

And as The Eucalyptus restaurant evolved in the years after it opened in 1986, famous chefs and foodies also found their way there, excited to discover a menu incorporating biblical foods, the Iraqi Jewish kitchen, traditional Arab and Jewish dishes from the Levant and foraged wild plants and herbs such as the now ubiquitous za’atar.

All this is reflected in the cookbook, which contains 100 recipes and took 10 years to complete. Basson’s daughter, Sharon Fradis, helped write and test recipes.

The forward is by doyenne of Jewish Sephardi and Middle Eastern cooking, Claudia Roden, who admits there is always something new to learn from Basson.

In the 30 years of their friendship, their adventures have included wild herb picking in the Jerusalem hills, shopping at Mahane Yehuda, and savoring Basson’s “magnificent” Moroccan cigar of duck and figs accompanied by a vanilla carrot puree and pumpkin jam, lamb with dates or balabouza jelly, based on Roden’s recipe but with the addition of rose petal jam.

“I love the way he combines flavors and textures and the way he marries ingredients, which are surprising and yet nostalgic, triggering almost forgotten memories,” she says.

Bringing memories to life

Basson’s own foray into cooking was first inspired by his mother reminiscing about eggs cooked over the embers of a bonfire when the family lived in Iraq. They left for Israel in 1951 following a farhud (pogrom) against the Jewish community.

The young boy managed to recreate the dish with the help of his sister (the first two experiments ended up in exploding eggs!). After picking up the scent of the cooked eggs, his mother hugged him for “bringing her memories to life.”

Other recipes in the book are inspired by his memories of the “wonderful traditional Arabic dishes cooked by our neighbors of my childhood, as well as the Iraqi dishes prepared by my mother, my grandmothers, and my aunts.”

His lifelong study of biblical foods led to dishes such as freekeh (called carmel in the Bible) risotto and bulgur tabbouleh.

In the book he explains how in the story of Absalom rebelling against his father, King David, there is a description of a woman spreading wheat to dry in the sun before cracking it into coarse or fine bulgur. In Arab villages, farmers still use this ancient technique.

The next generation

But Basson has never been stuck in the past. The ceviche recipes appearing alongside Moroccan fish kebabs with lemon cream and fish shawarma profiteroles are a testament to his welcoming of the next generation in the business.

His son, Ronny Basson, joined the restaurant after completing a post-army trip in South America. In Peru, he had discovered ceviche at the hip restaurants of renowned chef Gaston Acurio. The Eucalyptus version “adds a layer of olive oil to coat the fish keep its texture firm. The kohlrabi was an added inheritance from the vegan version. We found it complements the dish and adds balance.”

Basson’s philosophical thoughts on the senses are also revealed to readers.

In the chapter “Salt and Precision,” he muses on his mother’s tomato-mint soup, which has been a constant flavor in the family’s life, even though “she cooks without even tasting.”

Basson puts this precision down to using your “nose when you cook. Allow your own sense of taste and smell to guide you through the process.”

The chef, the man, the times

In speaking with ISRAEL21c, Basson reveals himself as a man of resilience and positivity.

Even though his US book tour, which was scheduled to begin October 9, was cancelled and his restaurant shuttered for 130 days after the October 7 Hamas attacks, the chef begins our discussion on a positive note, talking about the recent exuberant rainfall which has resulted in a bounty of the elusive morel mushroom.

“It’s a mushroom supermarket out there,” he says excitedly when describing the Ben-Shemen Forest, his foraging stomping ground conveniently adjacent to his home.

Basson is also enthusiastic about planning new dates for his book tour, which will include talks and cooking demonstrations.

He is unperturbed by any assertions that may come about Israeli appropriation of Palestinian or Arab dishes.

“I belong to the Middle East. I am not just Israeli but an Arab Jew. All the borders are artificial. We are one plate, or ‘platter’ as we say in Hebrew. We have the same ingredients throughout the region, give or take. When someone says you took makluba [an upside down rice and meat dish] from us, I just laugh. It has roots in Iraq and is not exclusively Palestinian. So, nothing here is yours or mine. It belongs to the land.”

Basson is looking forward to preparing a meal for the pope, an initiative in the pipeline since he was featured in the Netflix series Stories of a Generation–with Pope Francis.

The documentary features heartwarming stories from men and women over 70 sharing poignant life lessons and pivotal choices in their journeys and bills Basson as a “celebrated chef who helps to show the dignity and rewards of hard work.”

Hard lessons of October 7

Basson, a founder of Chefs for Peace, is also a realist and says that what happened on October 7 did shatter a lot of his beliefs and that the situation does not allow the 20-year organization to return to regular activity.

“We had a discussion after the atrocities and one of the members did come out and condemn both sides. But until now, no one is saying anything outright that says you can’t compare anything to what Hamas carried out.”

Regardless, when the activity does resume, “everyone will be welcomed with a hug regardless of religion and nationality.”

Basson is also trying to maintain the equilibrium of the Christian, Muslim and Jewish staff at the restaurant, whose relations have always been harmonious. One of the Arab staff members, who has worked at the restaurant since he was 16 and had his wedding party there, suffered a personal loss when a peace activist from Kfar Aza who had ties with his family was murdered on October 7.

Now’s the time

Basson is very clear that it wasn’t an easy decision to reopen the restaurant (a scenario he knows well from the intifada, when it was shuttered for years and not just months). He went “back and forth and up and down driving myself crazy before making a decision,” he shares.

To date, half of his clientele has not returned. There are locals away on reserve duty or experiencing economic difficulty, foreign tourists putting travel plans on hold, and many people just not in the mood for eating out.

Still, Basson believes that now is exactly the time to believe in ourselves and preserve the hope that yihiye b’seder (all will be okay) and that we will flourish again.

“We have always been resilient and now is no exception,” he says resolutely.

For more information about The Eucalyptus, click here.