The entire childbirth history of a woman’s mother should be taken into account when assessing her risk of giving birth prematurely — before the 37th week of gestation — according to a landmark retrospective study examining the results of the deliveries of more than 2,300 mothers and daughters over a 22-year period (1991 to 2013) at Soroka University Medical Center in Beersheva.

Previously, the medical community was aware of a maternal connection indicating that women born prematurely were more likely to deliver their own infants early, too.

The new study suggests that the circle should be widened to include prematurely born maternal aunts as a medical indicator for preterm deliveries.

The study, published recently in The American Journal of Perinatology, found that the risk of preterm delivery was 34 percent higher for women whose own births had been premature.

Unexpectedly, the study also revealed that if one of her sisters had been born prematurely, the mother’s risk of going into labor and delivering a baby early was 30 percent higher than normal. The risk remained significant even after adjusting for factors such as the origin and age of the mother.

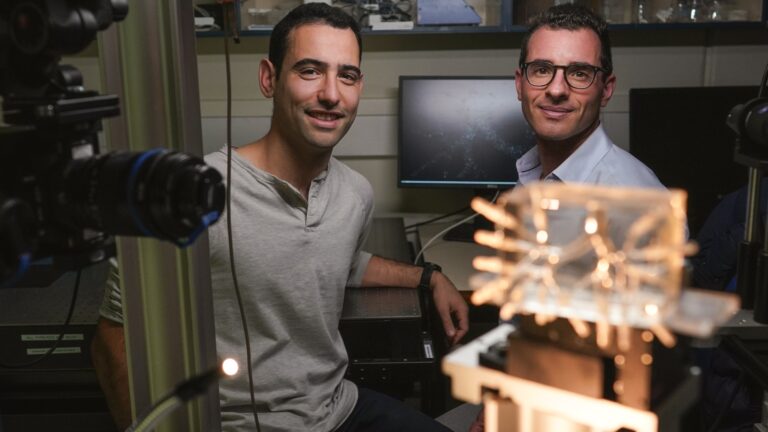

“The results of the study show that the mother and aunts should also have a medical history when considering the risk of pregnancy complications such as premature birth,” said Dr. Eyal Shiner, director of obstetrics and gynecology at Soroka and a member of the research team.

Preterm birth is the leading cause of infant mortality and also the most common cause of prenatal hospitalization. Therefore, said Shiner, “Women who are at risk can benefit from close monitoring and early detection of genetic markers.”

The researchers note in their summary of the study that exposure to events, situations and/or substances in one generation can affect the growth and development of the next generation.

“Intergenerational influences may reflect both lifestyle and genetic factors shared by both generations,” they write. “It has been suggested that delivery outcomes, as a result of maternal influences, occur on three levels: the genome, the fetal environment (with possible inherited complications from this environment), and mitochondrial inheritance. Meaning the possible influences can be genetic or epigenetic.”

In addition to Shiner, the study was carried out by Dr. Yoni Sherf of Soroka as well as professors Natalia Bilenko, Ilana Shoham-Vardi and Ruslan Sergienko from the department of public health at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Beersheva, which is affiliated with the 1,100-bed Soroka.

One of Clalit Health Services’ 14 hospitals, Soroka is Israel’s busiest medical center, serving the entire Negev population of more than one million, including 400,000 children. The hospital’s maternity unit staff delivers more than 16,000 babies each year.